Romanticism and Fantasy: William Wordsworth, Part Two — The Prelude

This post is part of an ongoing series about fantasy and the literary movement called Romanticism, specifically, English Romanticism in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The series began with this introductory post, continued with an overview of the neo-classical eighteenth century that the Romantics revolted against, considered the Romantic themes in English writing from 1760 to about 1790, then looked at elements of fantasy and Romanticism in France and Germany before returning to England to consider the Gothic. I wrote about the work of William Blake here, and last time I began a consideration of fantasy elements in the work of William Wordsworth.

This post is part of an ongoing series about fantasy and the literary movement called Romanticism, specifically, English Romanticism in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The series began with this introductory post, continued with an overview of the neo-classical eighteenth century that the Romantics revolted against, considered the Romantic themes in English writing from 1760 to about 1790, then looked at elements of fantasy and Romanticism in France and Germany before returning to England to consider the Gothic. I wrote about the work of William Blake here, and last time I began a consideration of fantasy elements in the work of William Wordsworth.

As I said then, Wordsworth is not a writer with many overt fantastic elements in his major works. Still, I find there’s a fantastic feel that emerges from the use of certain structures and imagery. Comparing his work to the motifs of fantasy fiction in Clute and Grant’s Encyclopedia of Fantasy, I found parallels between his use of nature and the way “the Land” has been imagined in secondary-world fantasy. The notion of “thinning,” the fading of enchantment and meaning, seems to resonate with Wordsworth’s poetry as well.

Bearing all this in mind, I want to look here at perhaps Wordsworth’s greatest accomplishment, The Prelude, his epic poem on the growth of his own mind. Before doing that, though, I want to introduce some more concepts from the Encyclopedia of Fantasy, and then bring in some ideas from M.H. Abrams’ excellent critical study of Romanticism, Natural Supernaturalism. And with all that will come some ideas from J.R.R. Tolkien.

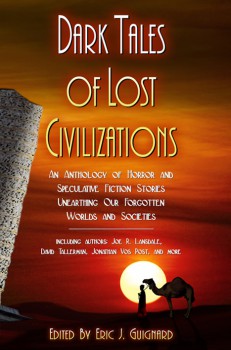

Dark Tales of Lost Civilizations: An Anthology of Horror and Speculative Fiction Stories Unearthing our Forgotten Worlds and Societies

Dark Tales of Lost Civilizations: An Anthology of Horror and Speculative Fiction Stories Unearthing our Forgotten Worlds and Societies

Update:

Update: