Medical Alternative History: The Wages of Sin by Harry Turtledove

|

|

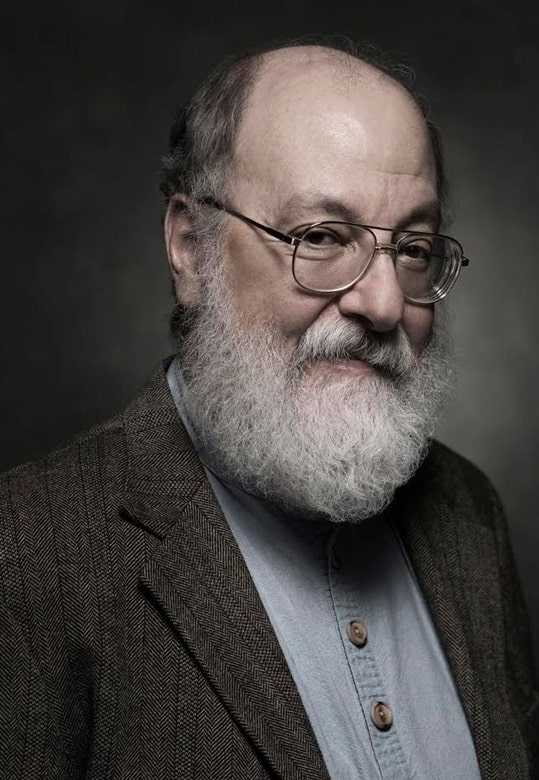

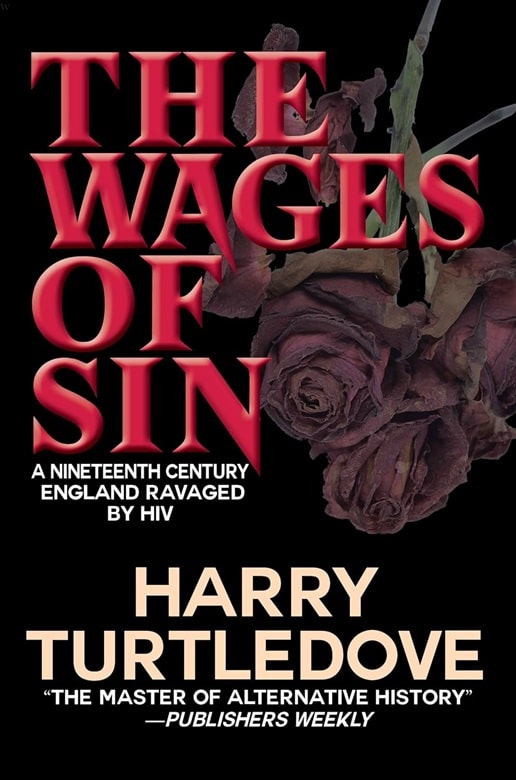

The Wages of Sin (Caezik SF & Fantasy, December 12, 2023). Harry Turtledove photo by Joan Allen

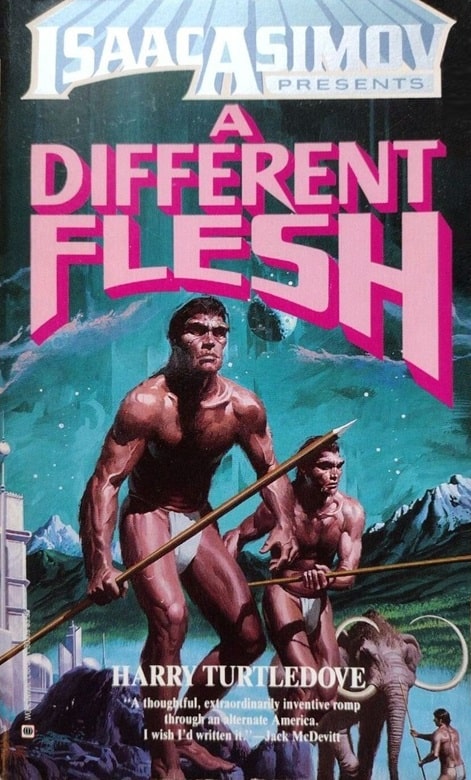

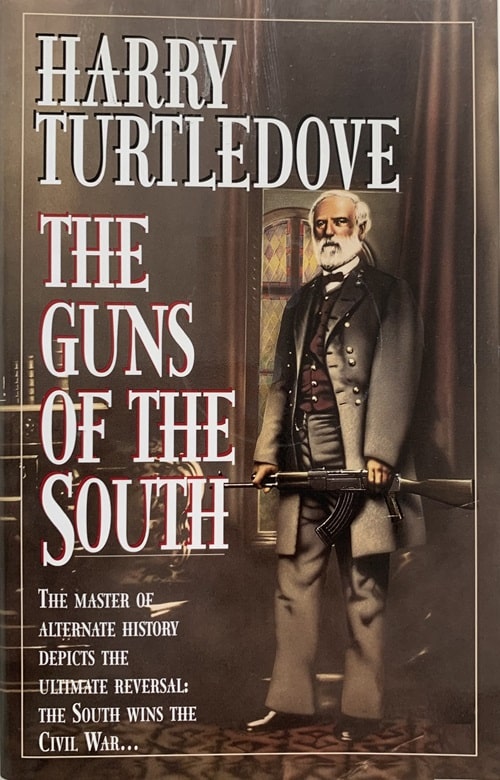

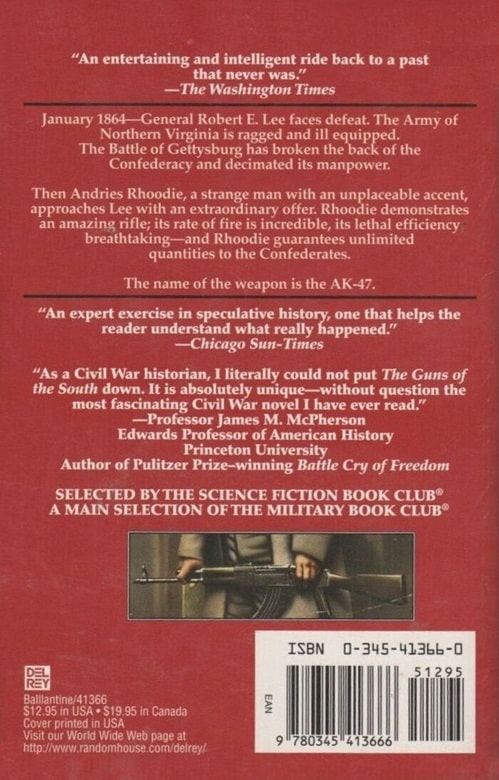

Harry Turtledove has been writing alternative history for a long time: His early stories included those that became A Different Flesh, set in a world where the Americas were inhabited by Homo habilis rather than Homo sapiens, and The Guns of the South, portraying a Confederate victory in the American Civil War, confirmed his standing in this particular subgenre. A large share of his work has explored the two big premises for the genre: reversed outcomes in the Civil War and in World War II — sometimes as straight AH, and sometimes as science fiction (as with the alien invasion during World War II of Worldwar) or even fantasy (as in the created world consumed by a parallel to World War II of The Darkness). Such premises seem to have a huge appeal for fans, going back to Winston Churchill’s “If Lee Had Not Won the Battle of Gettysburg” in J. C. Squire’s anthology If It Had Happened Otherwise, published 1931.

Turtledove’s newest novel, The Wages of Sin, is a refreshing change of pace, taking place before the time of either war, and with a point of departure that’s not military at all, though equally grim in a different way. Following a long established tradition of AH, he starts out by showing the point of departure, which provides the premise for his world: the transmission of HIV from Africa to Europe in the year 1509, in a world where there is no chance of an effective treatment for it. His second chapter begins in 1851, in an England that has come to such terms as it can with “the Wasting,” and has been changed by doing so.

[Click images for larger versions.]

|

|

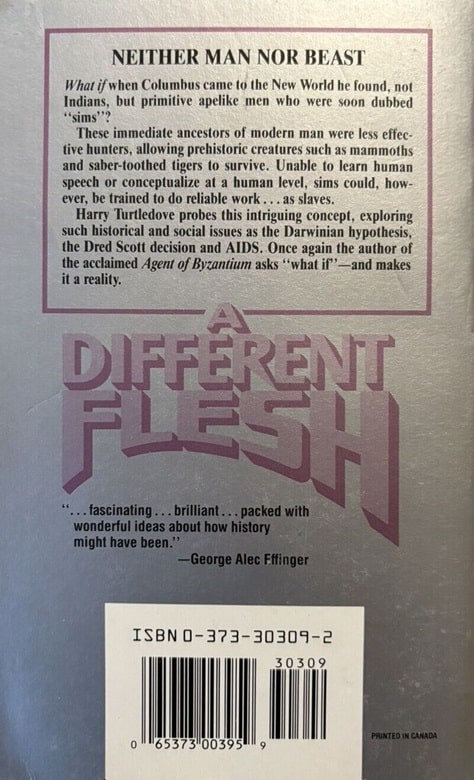

A Different Flesh (Worldwide Library, May 1989). Cover uncredited, but likely Vincent di Fate

(I have to say that it might have been interesting to see the novel start at that second chapter, with the origins of the Wasting established purely by indirect exposition, in a more purely science fictional style. There are already several points in the novel where the development of the Wasting since 1509 is conveyed in that way; a little more retrospection could have fitted in without straining the flow of the story. Explicitly describing the point of divergence is a long established convention of AH, but I’d be curious to see the results of setting it aside.)

Turtledove’s story in many ways is like the British novels of the real nineteenth century. It starts out with a betrothal of a young man, Peter Drinkwater, and a young woman, Viola Williams, in the city of Salisbury. Shortly afterward, he goes to London to study law. She remains behind, leading a largely secluded existence, as women are required to in this version of England, and they correspond.

|

|

The Guns of the South (Del Rey/Ballantine, May 1997 reprint edition). Cover by by Tom Stimpson

Much of the plot turns on matters that novelists of the real nineteenth century would have hesitated to address — though William Blake had already written, in the Songs of Experience of 1794,

How the youthful harlot’s curse

Blasts the new-born infant’s tear

And blights with plagues the marriage hearse.

On one hand, Peter is assigned a roommate, Walter Heywood, who regularly risks visiting brothels, confident that he’ll escape the Wasting, and endeavors to persuade Peter to join him. On the other, Viola, fond of reading travelers’ tales (including Alfred Russel Wallace’s recently published Voyage of the Basset), undertakes to write one of her own, about a ship in the little-explored Pacific Ocean finding the imaginary land of Temecula, where the Wasting has never been introduced and women are the equals of men in law and custom. (I thought “Temecula” was a neat little joke; I used to live half an hour’s drive north of Temecula, California, not far from Turtledove’s home.)

The first four novels in The Darkness saga by Harry Turtledove: Into the Darkness,

Darkness Descending, Through the Darkness and Rulers of the Darkness (Tor Books, 1999-2002)

These events shape the plot, which turns almost entirely on Turtledove’s premise but at the same time is perfectly mundane, within the circumstances of his imagined timeline.

I have to say that it might be considered a fault that some of the plot developments that grow out of these situations are predictable. There were two, in particular, that I anticipated as early as Chapter IV. On the other hand, they led on to further turns that I found less predictable, so I can’t count them as more than minor flaws.

Turtledove works out the secondary historical effects of the Wasting in some detail. Africa has been identified as its source, and the Pope has banned the slave trade and commerce with African peoples. This affects England, because Henry VIII died young, and England never broke with the Catholic Church; there are priests and monks in its streets. It also appears that Scotland remains independent; perhaps Elizabeth never came to the throne, or was never born, and thus didn’t choose James VI as her heir.

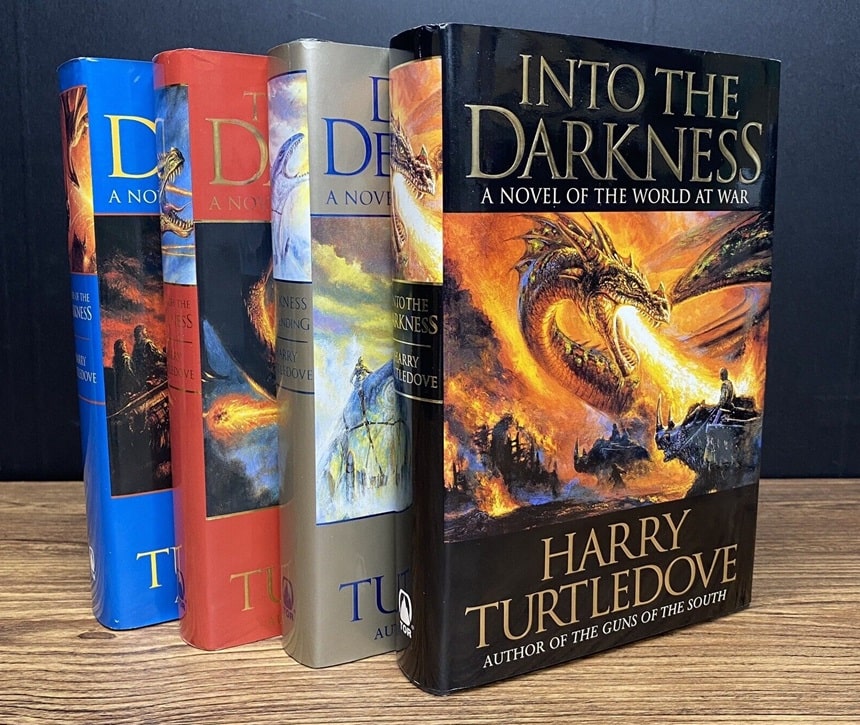

Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift. 1726 First edition

Literary history has changed as well: Christopher Marlowe wasn’t murdered, but died of the Wasting at around fifty, with no rival as England’s greatest playwright; and it appears that Jonathan Swift never wrote Gulliver’s Travels, as Viola’s A Voyage to the Island of the Temeculans is received as a strikingly original work. (In effect, it’s a kind of science fiction, the science being navigation, in an era when unknown lands and strange cultures could be placed overseas, rather than on Mars or Venus.) This kind of detail is one of the pleasures of AH, and Turtledove, as usual, is good at it.

Much of the novel looks at the details of everyday life in Turtledove’s world, and in particular at the sequestration of women, imposed as an attempt to limit the spread of the Wasting. Women characters spend most of their time indoors, in sections of their houses that are off limits to male visitors. On the rare occasions when they go outside — to shop, for example — they wear garments that cover everything except their eyes and hands, though they are still targets for catcalls or groping from men.

There’s no mention of any domestic servants, though both the Williams and Drinkwater households are reasonably prosperous; I can understand the absence of manservants, but I’m not sure how Turtledove got to not having cooks or housemaids. That’s one of the big departures from actual nineteenth-century novels, where servants are omnipresent, and I think it could have used a little more justification.

An old custom of AH, going back to Churchill’s essay, is to have its people speculate about how things might have been otherwise — in effect, to try to imagine us. Viola’s book isn’t a venture into AH, but it seems to play a similar role, offering an ironic commentary on Turtledove’s setting through the medium of an imaginary society. It’s a good use of this particular literary conceit.

And, finally, a big part of a novel’s appeal is its characters. Both Viola and Peter were a pleasure to read about. They both had flaws enough to make them interesting, and to help create a plot, and there are believable tensions and conflicts between them. But ultimately they both appear as good people trying to cope with difficult circumstances. The same can be said about Viola’s father, whose relationship with her is somewhat like that of Jane Austen’s Mr. Bennett to his daughter Lizzie; there are good conversations between them on varied subjects. And as a doctor, he’s able to provide the reader with information about the medical aspects of the setting, and to speak for the sheer helplessness of medicine before the Wasting.

Peter’s roommate, a far less sympathetic figure, provides a view of libertinism and the terms on which it survives in Turtledove’s world. These and many secondary characters make The Wages of Sin persuasively similar to classic British novels of our own nineteenth century — which gives the alterations a greater impact.

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels. His last article for us was a review of Courtship Rite by Donald Kingsbury.

Hmm. The last Turtledove I picked up was part of Worldwar, and sometime in 2000. After that, his work seemed to disappear from the bookstore shelves where I was living. This one sounds interesting… I wonder if he’s back on the shelves.

I think I got a recommendation from Amazon. I checked and my city library had it, so I borrowed it, wanting to take a look at it. I thought it was actually rather good; I may buy a copy

My local library is struggling. They won’t have this. …Maybe wherever I can get it will have two copies, so that one can go to the library! That would be good. (Am slow to think of these things.)

Does Temecula, CA, bear any resemblance to the Pacific land of Temecula in the book? Or was the naming the extent of Turtledove’s joke?

I don’t remember there being any emphasis on the climate of the remote land of Temecula, but Temecula, CA is in the desert and has hot, dry weather, with rainfall almost entirely in the winter months, a climate that would have been quite exotic to Viola. For the rest, I saw very little of Temucula, CA, but nothing about the fictional Temecula seemed like other cities in that part of southern California such as Riverside or San Bernardino. I think Turtledove was just going for the incongruity of using the name of a very mundane place for a remote, fantastical land.

Happily, the city library of Lawrence, KS has shelves and shelves of science fiction, and fantasy, and urban fantasy (separately), and horror, AND comics/graphic novels/manga. It doesn’t seem to have much in the way of older classics, but it does make an effort to keep up with current releases.