Love Exotic Science Fiction on Desert Planets? Try Donald Kingsbury’s Courtship Rite

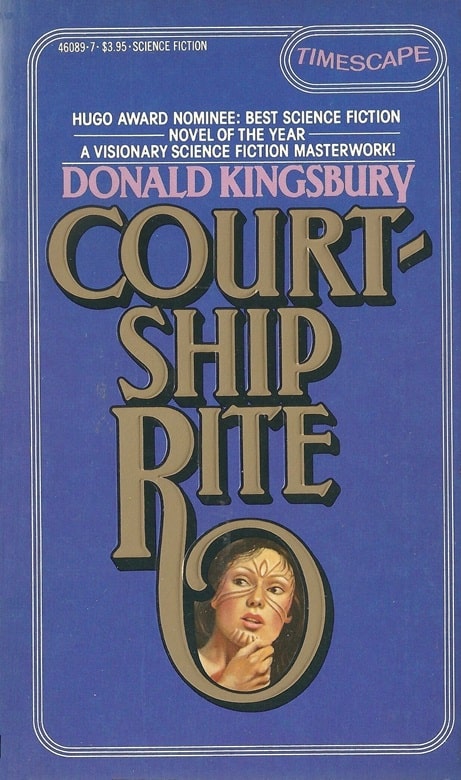

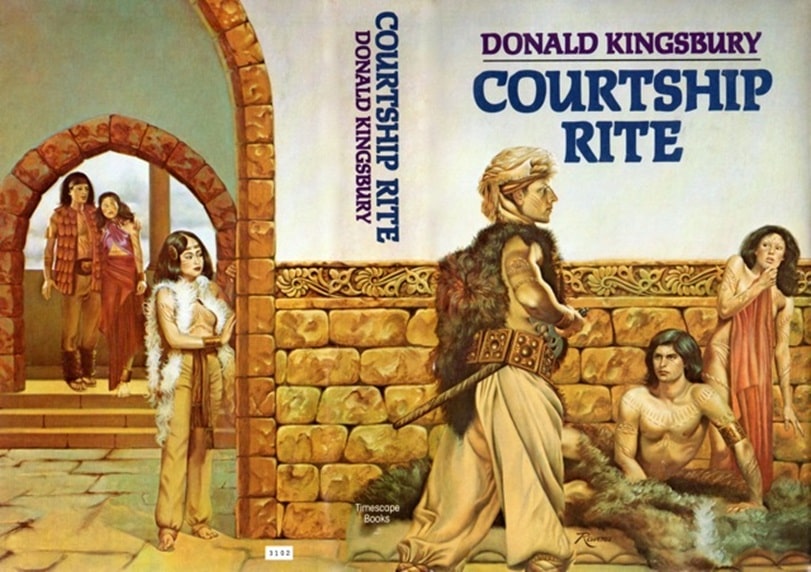

Courtship Rite (Timescape Books, July 1982). Cover by Rowena Morrill

Noe took her strange Liethe in a comforting embrace. “Some of us make our Contribution to the Race through Death, and others of us make our Contribution to the Race through Life. That’s the way it has always been.”

One of the distinctive pleasures of science fiction is the heterotopia — a story set not in a good place (a utopia) or an evil place (a dystopia) but in an interestingly different place. Geta, the setting of Donald Kingsbury’s Courtship Rite, has long been my favorite heterotopia.

The society Kingsbury portrays is shaped in important ways by its physical setting. Geta is a desert world, a science fictional trope that goes back to Percival Lowell’s Mars and the many stories set there, from Burroughs on. It’s not as harsh as Herbert’s Arrakis, but certainly harsher than Le Guin’s Anarras. For one thing, its native life is biochemically incompatible with its human inhabitants; eating it, without careful detoxification, is lethal. The only things truly safe to eat are a limited number of introduced Earth lifeforms: bees, eight species of plants (not all named) — and other human beings, because Geta’s most visibly distinctive cultural trait is institutionalized cannibalism. Kingsbury calls this out on the first page of the novel, where the children of a famous man, Tae ran-Kaiel, attend a funeral feast where his roasted body is the main course.

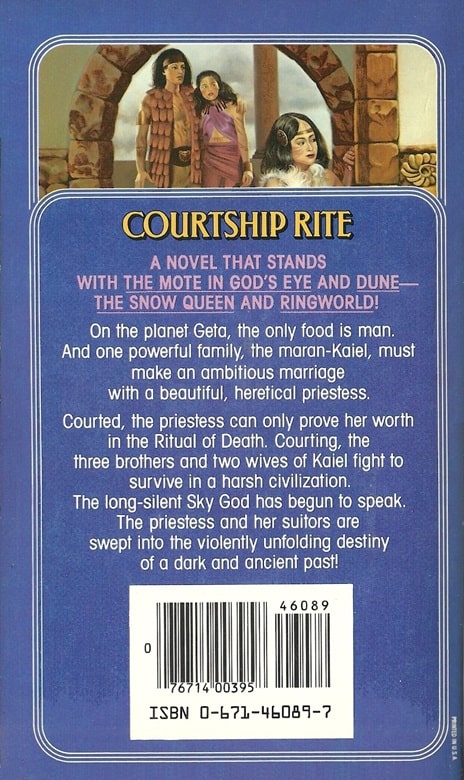

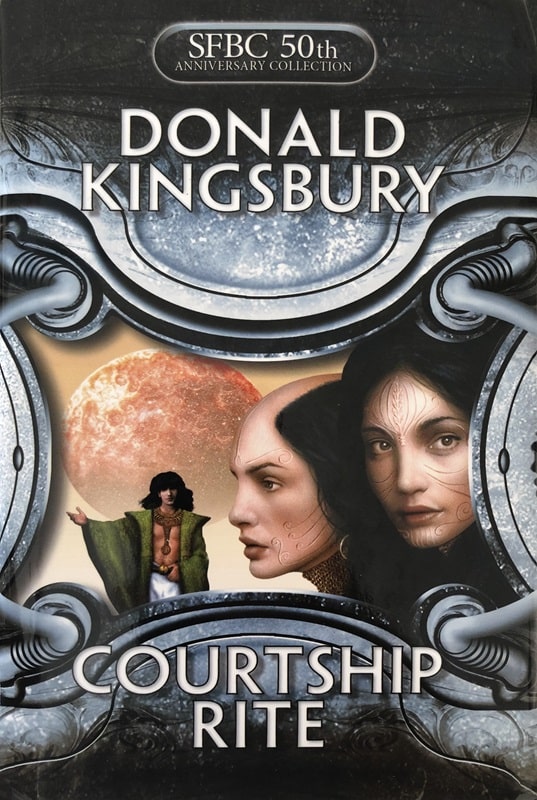

Courtship Rite, Science Fiction Book Club 50th Anniversary

Collection #29 (SFBC, July 2006). Cover by Jim Burns

Three of those children take the first step toward becoming central actors of the story, by taking the vow to become co-husbands, though as yet they have no prospective wife in view: Gaet, Hoemei, and Joesai maran-Kaiel. The action begins a few years later, when they’ve found two wives, Noe and Teenae, and are looking for a third.

They think they’ve found one, Kathein pnota-Kaiel, but Aesoe, Tae’s successor as head of the clan, has other plans: He orders them to court and marry Oelita, a woman who belongs to no clan, and adheres to heretical ideas, but who has a large following among the people of a region open to Kaiel expansion. Joesai undertakes at the same time to comply with this order and to thwart it, courting Oelita by the Death Rite, a ritual in which she has to pass seven potentially lethal trials to prove her fitness to marry.

The conflict between Oelita and Joesai is one of the movers of Kingsbury’s plot. But other conflicts are also vital: between Joesai and Teenae, who admires Oelita; within the maran-Kaiel, over whether to marry Oelita or Kathein; between Aesoe and the maran-Kaiel, especially Hoemei, who is a potential rival to Aesoe’s leadership of the clan; and between the Kaiel as a whole and the Mnankrei, a rival priest clan who also want control of the territory where Oelita lives, and use much more destructive methods to gain it.

I’m impressed by how ingeniously Kingsbury ties all of these conflicts together: the resolution of the larger political conflict puts stress successively on all the more personal points of conflict, each of which also has political ramifications.

Only a hermit can avoid talk of weddings and politics.

– A saying of the Kaiel

Oelita’s heresy has several aspects. She denies the existence of God, in a certain way: She can see God orbiting overhead, brighter than any star, but she believes God is simply a rock. She rejects the story that human beings were brought to Geta by God, and suggests that they evolved by natural selection from a large marine insect.

|

|

Courtship Rite (Timescape/Pocket Books, September 1983). Cover by Rowena Morrill

This makes her sound like a rational, scientific thinker confronted with religious fundamentalism — but Kingsbury is making an ironic point: Oelita is a brilliant autodidact, unaware of the facts that speak against her theories, such as the genetic incompatibilities between human beings and Getan life. Finally, Oelita rejects cannibalism, proposing other methods of maintaining fitness, and has a growing following who share her beliefs. The novel’s single most dramatically intense scene shows her confronted by new evidence that challenges her atheism.

The Getan word for “fitness” — one of a handful of words given in the Getan pronunciation, rather than “translated” into English — is kalothi. This looks as if it may have evolved from “quality.” It has a primarily biological meaning, in that it’s something that a clan can try to improve through breeding rules.

That suggests social Darwinism, but in fact Getan beliefs differ from the usual interpretations of social Darwinism in important ways. For one thing, kalothi is multidimensional, and different clans can pursue it by selecting for different things: for tolerance of more toxic native life in their diet, for the ability to travel long distances and carry heavy loads, for mathematical ability, or, in the case of the Kaiel, for the ability to foresee the long-term consequences of proposed policies.

A large part of the conflict between Aesoe and Hoemei in fact reflects different visions of the Kaiel future, and the future of Geta. A further difference is the Getan maxim that kalothi can always be overwhelmed — but this means that superior physical force or military strategy isn’t evidence of kalothi; the Getans don’t admire what Nietzsche called the “brute blond beast.”

Biology is central to Kingsbury’s story. Geta is a version of an old science fictional theme: A world and culture whose science is primarily biological rather than physical. The Getans have been doing not merely selective breeding but genetic manipulation since before the discovery of electricity, and even of the bicycle.

Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, with the first installment of

Courtship Rite. February 1, 1982. Cover by John Lakey and Val Lakey

This is a point where Kingsbury’s science fiction may not be as hard as it seems: The priest clans, the Kaiel and Mnankrei and even the lesser Stgal, all make use of molecular genetics, but the structure of DNA was discovered by X-ray crystallography, which required advanced knowledge of the physical sciences. (On the other hand, one reviewer suggests that the Getans are using engineered microorganisms rather than physical technology to do their genetic engineering.)

“The largest insects are in the maelot class. The ones who have returned to the sea can be as large as your leg. Wrong amino acids, though. Wrong replication coding. Not logical. We are closer to the bee than to the maelot. We are even closer to wheat than to the maelot.”

For all that, Courtship Rite has a lot of merit as a science fiction novel. It has been out of print for a long time, and has never had an e-book version; it deserves republication.

In the first place, on my latest rereading, just completed, I was struck by how sophisticated its literary design was. It has many of the formal attributes of a comedy, being the story of a courtship that is hindered by misunderstandings and that ends with a wedding. In particular, there is the important role played by the Liethe, a clan of parthenogenically reproducing women who act as entertainers and courtesans and who identify themselves as servants to priest clans such as the Mnankrei and the Kaiel; their various genetically identical lineages are able to play tricks with swapping names and identities.

One of the Liethe, the se-Tufi Who Walks in Humility, plays the role of a clever servant, stealthily intervening when the maran-Kaiel are in difficulty. Another attribute is the repeated use of formal ritual, from the recitation of Kaiel clan law in the first chapter to the complexities of the Death Rite by which Oelita is courted to the wedding ceremony in the final chapter.

French edition: Parade Nuptiale (Folio SF, March 6, 2003)

In the second place, Kingsbury provides intellectual content focused on his themes. The primary theme of Courtship Rite appears to be kalothi. But kalothi is attained through a process of optimization, a topic Kingsbury was familiar with as a mathematician. And Kingsbury explores it, not only in relation to population genetics, but also in social and political processes and in ethics.

His particular heterotopia reflects this idea at many levels, giving it unusual coherence, and his characters discuss and debate it — for example, in the penultimate chapter, where three young Kaiel, waiting to watch the wedding in the final chapter, debate whether expansion is better served by military strength or by building alliances. Part of this novel is intellectual comedy, expressed through dialectic (in the Socratic, not the Marxist sense — though the later part of the novel includes several debates with the rediscovered works of Lenin!).

Even beyond that, in the last place, his central characters are embodiments of kalothi, each in their own way. Hoemei, Gaet, and Joesai fit the familiar distinction between being good at ideas, people, or things (in the first chapter, Hoemei eats some of their father Tae’s brain, Gaet of his heart, and Joesai of his thighs). Their first two wives are talented in different ways; Oelita and Kathein are extraordinary, making it almost impossible to choose between them.

And the events of the story bring all of their abilities and all of their differences into focus. Even Aesoe, who emerges as their ultimate adversary, is an impressive monster and in many ways the prime mover of the story. This cast of characters may be the ultimate reason I fell in love with Courtship Rite when I first read it and enjoy it even more now, decades later.

O brave new world, that hath such people in it!

– Shakespeare, The Tempest

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels. His last article for us was a review of the self-published SF novel April by Mackey Chandler.

I need to reread Courtship Rite. I loved it when it came out.

Too bad John couldn’t find a copy of the cover of the UK edition of the novel, which was called Geta. But here’s one:

Donald Kingsbury is an interesting character. I’ve discussed him several times recently (including here at Black Gate I believe?) He may be the oldest living SF writer. And he has supposedly been working on a novel called The Finger Pointing Solward for, oh, neearly 70 years now! It was rumored to be close to publication in the mid-2000s. I suspect now that it will never see publication until after Kingsbury’s death.

I’ve wanted to read The Finger Pointing Solward for decades. I hope that Kingsbury’s work gets revived one of these days; he’s a remarkable writer, both literarily and ideationally.

Dang it, Rich! Now I really want a copy of Geta…

Surely you mean you want to get a Geta!