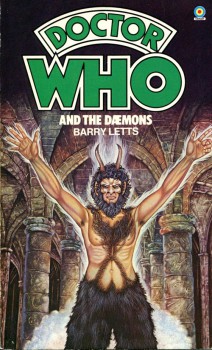

Doctor Who and the Daemons – the Novel!

More than once on Black Gate, I’ve heard that the seventies were a dead zone for science fiction and fantasy. For teens in search of readily available genre “gateway drugs,” I suppose this might have been true for many, but my particular experience of growing up managed, against all odds, to be different. Ohio was my home base, a vanilla environment for “culture” of the fantastical sort, but luckily I had a smorgasbord of British relatives. One especially perceptive and sibylline aunt started sending me Doctor Who novelizations.

More than once on Black Gate, I’ve heard that the seventies were a dead zone for science fiction and fantasy. For teens in search of readily available genre “gateway drugs,” I suppose this might have been true for many, but my particular experience of growing up managed, against all odds, to be different. Ohio was my home base, a vanilla environment for “culture” of the fantastical sort, but luckily I had a smorgasbord of British relatives. One especially perceptive and sibylline aunt started sending me Doctor Who novelizations.

Doctor Who and the Dinosaur Invasion, that was the first I tried. Next, one of the best offerings in the canon, Doctor Who and the Auton Invasion. I was in third grade and after facing down those blank-eyed Autons and their Nestene masters, I was hooked.

Note that I wasn’t in any way watching the TV show. In Columbus, Ohio, it simply wasn’t available, not until the early eighties, and then, when PBS did pick up a few random episodes, it was Tom Baker’s roost to rule. The Jon Pertwee, Patrick Troughton, and William Hartnell adventures I first encountered were absent entire.

What Tom Baker’s run taught me is that talented actors can be mired forever in substandard scripts and even worse special effects. This was a total and unpleasant surprise, because the novelizations were fast-paced genre gems, especially those penned by Terrance Dicks. (Malcolm Hulke was the other regular adapter for the Doctor Who franchise, with a rotating cast of fellow contributors including Gerry Davis, Ian Marter, and David Whitaker.) How could such pacey, adrenaline-filled books arise from such hokey, hamstrung screen material?

A little while ago, I stumbled on a book that seemed especially worth writing about here: The City, by Stella Gemmell. It’s Gemmell’s first solo novel; she also completed Troy: Fall of Kings, the last book by her late husband, David. David Gemmell was a widely-known heroic fantasy writer — those unfamiliar with his work can see

A little while ago, I stumbled on a book that seemed especially worth writing about here: The City, by Stella Gemmell. It’s Gemmell’s first solo novel; she also completed Troy: Fall of Kings, the last book by her late husband, David. David Gemmell was a widely-known heroic fantasy writer — those unfamiliar with his work can see

Two years ago, veteran author Mary Gentle’s most recent novel The Black Opera was published to mixed reviews. Some liked the book’s mix of alternate-history fantasy and comic-opera theatricality — as the sub-title has it, “a novel of Opera, Volcanoes, and the Mind of God.” Others,

Two years ago, veteran author Mary Gentle’s most recent novel The Black Opera was published to mixed reviews. Some liked the book’s mix of alternate-history fantasy and comic-opera theatricality — as the sub-title has it, “a novel of Opera, Volcanoes, and the Mind of God.” Others,