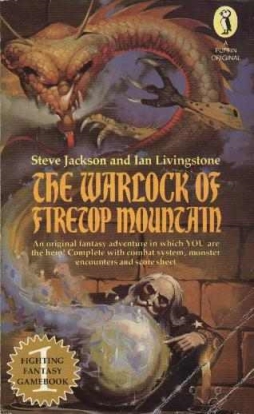

“A Fighting Fantasy Gamebook In Which YOU Are The Hero!”: The Warlock of Firetop Mountain

It’s a time for looking back, as the old year ends. Now so it happens that on a Boxing Day sale I picked up a book I loved as a child; and therefore it seems fitting to write a little about it, now, glancing back down the vanished days of this and other years, and to try to again see the pleasure I once had. Will it come again, as I work through the text? If I work on the text, then no. Because this text, more than most, is not made for working. It is a thing to be played.

It’s a time for looking back, as the old year ends. Now so it happens that on a Boxing Day sale I picked up a book I loved as a child; and therefore it seems fitting to write a little about it, now, glancing back down the vanished days of this and other years, and to try to again see the pleasure I once had. Will it come again, as I work through the text? If I work on the text, then no. Because this text, more than most, is not made for working. It is a thing to be played.

This is not a story I once loved, except in a way it is. There’s no strong central protagonist, except that in a way there is that as well. It’s a book-length riddle. It’s a maze through which you must find your way, filled with wrong turnings and frustrating locks. It is a story you can shape with a pencil and two dice: you are a hero with a sword, who must explore a wizard’s underground lair, before finally defeating the great mage in battle and taking his treasure. You choose your own adventure, flipping from one numbered section to another depending on the decisions you take faced with a given situation. More than most novels, the reader must shape the story; for the reader is the hero. This is The Warlock of Firetop Mountain, written by Steve Jackson and Ian Livingstone. First published in 1982, it was the first of what became a line of several dozen gamebooks, as well as a full-fledged role-playing game. Warlock inspired direct sequels, a computer game, and even several non-interactive novels. You can learn more about the books at their web site.

Not long ago, Black Gate’s redoubtable Nick Ozment looked at The Warlock of Firetop Mountain and several other of the Fighting Fantasy gamebooks. Nick remembered playing other Fighting Fantasy books, but not this one specifically. My experience roughly mirrored his: it was relatively easy to get to the end of the book, but incredibly difficult to actually win a complete victory. Nick liked the art — Firetop’s profusely illustrated by Russ Nicholson (you can see some of these pictures below) — but found the conception of the book’s dungeon improbable. I agree with both points. But I found myself wondering if there wasn’t something else to say about the book. I remembered playing through it in the early 80s, drawing out maps, trying again and again to make it through to the end. Why was I held so deeply in the book’s spell? Does it hold up?

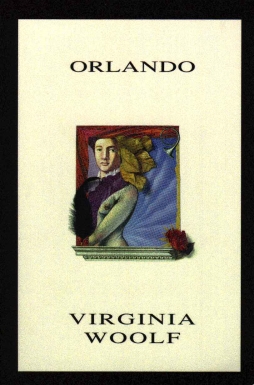

For some years now I’ve been wanting to reread Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. I first read the book about twenty years ago, and though I enjoyed it I came away confused. I felt as though on some level I really hadn’t understood the book. As though I hadn’t grasped how to read it. So, time having passed and me having (maybe) come to understand a bit more about books and reading, I sat down with Orlando again. And, as I’d hoped, I enjoyed it more thoroughly this time around, and felt as though I’d understood it a little better than I had. What surprised me was the reason for that understanding. I felt as though I’d worked out how to approach the book not because of any greater knowledge of modernism, or even because I’d read other books by Woolf, but because I now had a greater experience of early fantasy. More than I’d remembered or understood when I first read the book, Orlando is of a piece with the fantastic fiction of its time.

For some years now I’ve been wanting to reread Virginia Woolf’s Orlando. I first read the book about twenty years ago, and though I enjoyed it I came away confused. I felt as though on some level I really hadn’t understood the book. As though I hadn’t grasped how to read it. So, time having passed and me having (maybe) come to understand a bit more about books and reading, I sat down with Orlando again. And, as I’d hoped, I enjoyed it more thoroughly this time around, and felt as though I’d understood it a little better than I had. What surprised me was the reason for that understanding. I felt as though I’d worked out how to approach the book not because of any greater knowledge of modernism, or even because I’d read other books by Woolf, but because I now had a greater experience of early fantasy. More than I’d remembered or understood when I first read the book, Orlando is of a piece with the fantastic fiction of its time.