Burton in a Skirt, or What Are You Going to Do with Your Life when Game of Thrones Is Over?

Are you still trying to pull yourself out of the depression death-spiral you entered when you heard that the next season of Game of Thrones won’t appear until 2019? And do you find yourself going through every day in an ostrich-like endeavor to evade the knowledge that the next season of Game of Thrones will be the final season?

What will you do? What will you do?

Well, you could surrender to despair and binge-watch whatever the current iteration of CSI is (CSI Fresno? Arkadelphia? Mu?) until the foul odor of your sweaty, unwashed body drives away everyone you love and cherish.

Or you could do as your fathers’ fathers’… er… fathers (just old are you, kid?) did, yea, even as they wandered in the barren wilderness of the pre-internet, pre-fanboy, pre-CGI age: you could return to the source, the ancient fount from which Game of Thrones derives much of its overheated, multi-hued, melodramatic substance: the historical epics and biblical blockbusters and costume dramas that were Hollywood’s bread and butter from the silent era through the sixties, when the whole madcap caravan broke down by the side of the road, a victim of cultural change and economic vapor lock.

In the days before fantasy was cool or mainstream or even minimally respectable, before anyone but Cambridge dons had ever heard of J.R.R. Tolkien, before you could settle in front of your screen and gorge to bursting on the goings on in Westeros or Middle Earth or Shannara or Hogwarts, people went to movie theaters (remember those?) and took in Lawrence of Arabia or Sampson and Delilah, Ben-Hur or El Cid, Quo Vadis or The Crusades, Land of the Pharaohs or Spartacus. From Intolerance in 1916 all the way through the 50’s, the megalomaniac, big-budget, cast-of-thousands historical epic was one of the most reliable of all movie genres in terms of both critical approval and box office success.

Cecil B. DeMille and Friend

A lot of these movies — especially those by the master of the form, Cecil B. DeMille — affected a high moral tone, at least superficially, but no one was fooled. The filmmakers knew why people flocked to see these things, and it sure wasn’t because they had an irresistible urge to quaff a tall glass of pseudo-biblical buttermilk; that was often just the price of admission, the thing you had to swallow to get to the really good stuff. First a hymn or two, then the dance of the seven veils.

Folks lined up to see these movies because they provided the very things that today’s fantasy films and television shows offer — spectacular, large scale, wide screen doses of momentous-seeming sex, violence, and intrigue, all played out in colorful, exotic locales by outlandishly named characters wearing flamboyant (and skimpy) costumes. Then as now, that’s entertainment; the only downside was getting up after three and a half or four hours with a numb butt.

Intolerance (1916)

Galloping horses, garish palaces, sybaritic monarchs, angry deities, corrupt counselors, alluring priestesses, depraved princes, ill omens, whispering conspirators, cutthroat politics, clashing armies, poisoned entrées, desperate sieges, single combats, startling betrayals, bloody revenges, treacherous massacres — everything you can find in Game of Thrones you can find here, with the exception of dragons and three explicit sex scenes an hour. Oh, there was sex alright, but it was of the sultry smolder, clench and kiss, discreet fade-out variety. Suggestion was the order of the day; back then, people figured they could take care of anything more than that themselves once they got home.

The kind of spectacle that these films provided is common today in both fantasy and historical movies, but with this difference — in the days before CGI, the colossal sets, lavish costumes, screen-filling crowds, and gosh-wow special effects didn’t come out of a computer. They had to be literally engineered and built in the physical world, and that sense of reality continues to make these older films impressive in their heavy-handed way. Eye-fooling legerdemain was employed when economical or necessary, of course, but often you were actually seeing what you thought you were seeing. It makes a difference.

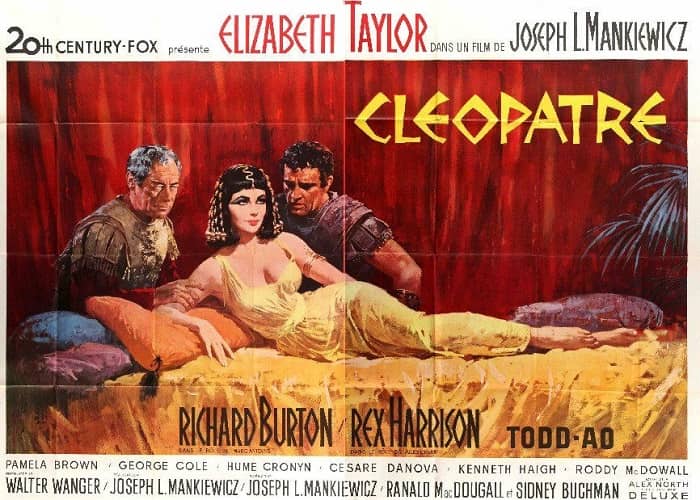

Cleopatra (1963)

Of course, every virtue comes with a corresponding defect, and costuming a thousand Babylonians, building a full size replica of the Roman forum, or recreating the battles of Alexander the Great can be very, very expensive. As long as box office remained strong, enormous budgets could be excused — indeed, when eye-popping spectacle was the main selling point, extravagant expenditures were a virtue (as long as all the money was “right up there on the screen,” in the words of the old cliché), but in the lean and mean “New Hollywood” era that dawned in the sixties, people began to see the epic historicals as stodgy and shopworn, and they stopped attending them in numbers sufficient to support the huge outlay such pictures required. When that happened the films — and Hollywood itself — collapsed under the weight of bloated budgets.

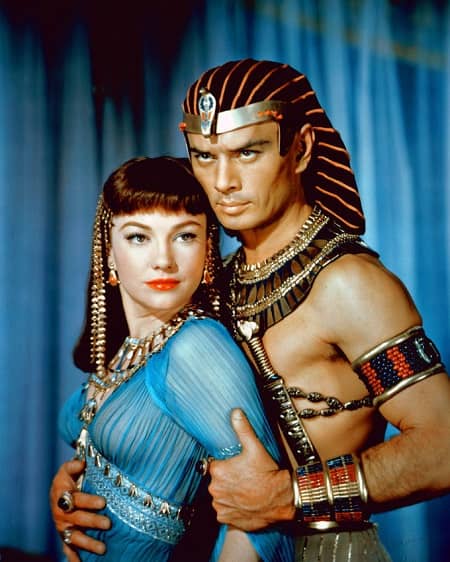

Villains — Yul Brynner and Anne Baxter

While the genre was still viable, though, it produced many films that can still provide a lot of fantasy-ish entertainment. Among the best are two DeMilles from the 30’s, The Crusades and The Sign of the Cross (as Claudette Colbert’s lewd Empress Poppaea bobs around in a huge tub supposedly filled with ass’s milk, you may well ask yourself, “Did I just see what I thought I saw?” Yes, you did.) The two mightiest peaks in the DeMille range, Samson and Delilah and The Ten Commandments, remain corny delights even after more than sixty years, the former climaxing with a sequence — the destruction of the temple of Dagon — that can still bring down the house, and the latter sporting four of the most delicious of all movie villains. Vincent Price as the lecherous and sadistic Baka the Master Builder, Edward G. Robinson as the wearily blasé and oh-so-oily Dathan the chief Hebrew Overseer, Yul Brynner as the ruthlessly ambitious Pharaoh Rameses, and Anne Baxter as the teasing, spiteful Queen Nefertiti are all so gleefully nasty that any of them could have been baddies on the Adam West Batman television show. (Indeed, years later Vincent Price and Anne Baxter did show up in Gotham City, as Egghead and Olga, Queen of the Cossacks. And come to think of it, Charlton Heston would have made a hell of a Batman… oh well. Too late now.)

Charlton Heston in El Cid

Speaking of Charlton Heston, his deep-voiced gravity, craggy good looks, and utter lack of irony made him a staple of these movies. In addition to his Moses in The Ten Commandments, he was of course Judah Ben-Hur in the film of that name (with a chariot race that still stands as perhaps the greatest action sequence ever filmed), Rodrigo Diaz in El Cid (a fine, neglected movie that features a meticulous recreation of medieval Spain and one of the screen’s most brutal, harrowing single combats), and General Charles “Chinese” Gordon in Khartoum (vitiated by pedestrian direction but worth seeing for its intelligent script and excellent performances).

Any of these movies and many more like them offer all the sex (well, almost), violence, intrigue, and spectacle that the most fervid fantasy fanatic could wish for. However, by the late fifties and early sixties, change was in the air, and perhaps the film that best exemplifies the gaudy excess of the epic historical at the moment when the genre’s succulent ripeness crossed the line into incipient rot is 1963’s Cleopatra, which has gone down in history as the movie that destroyed the Old Hollywood by virtually bankrupting a major studio (Twentieth Century Fox).

Cleopatra was actually a box office hit, but the studio spent so much to make and promote it (as the Egyptian queen, Elizabeth Taylor earned film’s first million dollar salary) that it had no hope of recovering its costs. (The final budget was thirty two million dollars, almost a quarter of a billion in today’s money.) Aside from its ill-famed importance as the faux-marble tombstone of the classical studio system, the movie is still fun to watch today because it’s a veritable smorgasbord of the very delicacies dear to the heart of every Game of Thrones lover.

Elizabeth Taylor

You want sex? In 1963, Elizabeth Taylor was in full… er, bloom, and the costumes or lack of them clearly signal the filmmakers’ determination to show as many acres of her as they could get away with, and whatever she’s wearing, her scenes with Richard Burton give off a real heat. This only makes sense, as the pair began a torrid affair during filming, leaving Liz’s then husband, the clueless Eddie Fisher, slashed and bleeding on the senate steps. Then there’s the scene where Cleo makes a pass at Julius Caesar (the ever-urbane Rex Harrison) by grabbing his hand and clasping it firmly to her ample bosom. The look on Harrison’s face at this moment is simply indescribable. Is it Terror? Bemusement? My-ship-has-finally-come-in bliss? Or just terminal wistfulness? (The poor chap was fifty six years old at the time. I have always wondered, though, how many takes that scene took. Rex: “Can we do it one more time? I’m still not quite feeling it.” Director: “That was the forty third take already, Rex!” Rex: “Just once more — I know I’ll get it this time, there’s a good fellow… “)

Violence!

You want violence? Egyptians lay siege to the Roman garrison in Alexandria, but are made mincemeat of by the military genius of Julius and by a legion full of Romans wielding sharp objects. (“Form the tortoise!” a centurion shouts. The surprising thing is how fast they do it.) Caesar gets stabbed a lot (by his close friends — isn’t that always the way?) and bleeds and declaims and falls down and dies. Octavian welcomes a peace emissary to Rome by running him through with a spear, albeit a golden one. (This was bad form even for the Romans, and don’t dare mention it to our rulers. Someone might get ideas.) Two huge fleets of Roman and Egyptian ships fling arrows and javelins and blazing globs of Greek fire at each other and then bash together and soldiers jump from ship to ship hacking and stabbing and a lot of them clutch their midriffs and groan and keel over or jump shrieking into flaming water. (That’s the battle of Actium in a nutshell, folks, and it’s actually very impressively done.) Throw in several suicides along the way and you have all the bloodthirsty diversion you can take and still have enough appetite for a good dinner afterwards.

Intrigue!

You want intrigue? The movie kicks off with Cleopatra’s brother and his slimy circle driving her into the desert after attempting to assassinate her. Then Caesar shows up and they scheme against him too (having already betrayed and murdered his rival Pompey before Caesar even got there). They don’t know that he’s doing his own counterplotting — unlike them, successfully. Back home Brutus and his gang whet their knives against Caesar and his ambitions, and once Julie has been ventilated, commemorated, and cremated, they draw a bull’s-eye on Mark Antony’s toga. Antony teams up with Octavian and plots right back. Later, Cleopatra, Antony, and Octavian all conspire against each other, and the musical chairs go on and on until the bitter asp. You can’t tell the conspirators without a scorecard, citizens.

Spectacle!

You want spectacle? There’s all of the aforementioned massive military action, plus the enormous and elaborate recreations of the Alexandrian waterfront and metropolitan Rome, the exhilaratingly vulgar Egyptian palace (Beverly Hills meets the mummy), Cleopatra’s entry into the Eternal City seated on a fifty foot sphinx pulled by a few hundred heaving, sweating extras (twenty bucks a day and a box lunch), and Cleopatra’s royal barge, which is like two blocks of downtown Las Vegas cut loose to float down the Nile River — it even has a floor show. No kidding!

And if that isn’t enough, Cleopatra also contains the finest of all examples of a phenomenon that you often encounter in this kind of movie, the spectacle (if I may use the term) of an actor — often quite a good one — rendered shamefaced and helpless by the indignity of having to mouth bad lines while wearing a silly costume.

Burton in a skirt

Richard Burton, dragooned into playing Mark Antony, was a fine actor, but when gazing at Cleopatra atop her mobile sphinx, he turns to Caesar and with a patently false heartiness says, “Nothing like this has been seen in Rome since Romulus and Remus!” the poor man’s humiliation is palpable. He’s completely unmanned by the goofiness of the line and the fact that his hairy, lumpish legs are exposed for all the world to see below a red and white, gilt-edged tunic that looks like it came off the rack at Consuls’ Wearhouse. He spends the rest of the movie in a state of utter demoralization, relieved only by brief squalls of embarrassed lust (Liz, you know). He checks out of a lot of scenes altogether, gazing melancholically into the middle distance, musing on the ruin of his ambitions. (In moments like this, Dick’s classical training comes back to haunt him, as a line from Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus runs in an endless loop through his head: “Why, this is hell, nor am I out of It.”) Clearly, all he wants is to get off the screen as quickly as possible, and in his acute discomfort he’s like a small boy who really has to use the bathroom but doesn’t dare mention it to any of the grownups around for fear of being hollered at.

Why, this is hell

I have dubbed this phenomena “Burton in a skirt”, and have found that it has application far beyond the bounds of mere movies. I have come to think of a Burton in a skirt as being any enterprise which fails through a collapse of confidence, especially when that collapse is due to a belated recognition of the project’s fundamental absurdity. Look around the world today and you can’t fail to see Burton in a skirt almost everywhere you look.

Don’t believe me? Try using Burton in a skirt at home yourself, risk-free for thirty days. If at the end of that time you aren’t completely satisfied, stop using it. What do I care?

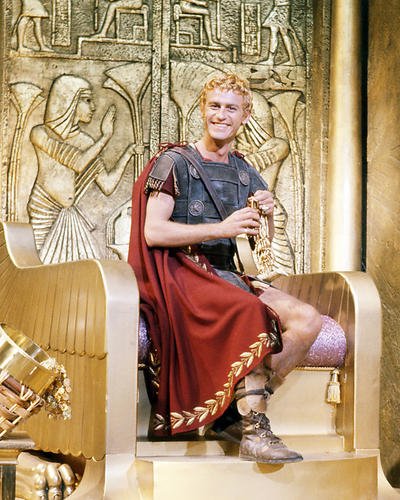

Roddy McDowall, having too much fun

I know I’ve made Cleopatra sound ridiculous and for much of its gargantuan length, it’s undeniably that. Harrison, Burton, and Roddy McDowall (enjoying himself way too much as a reptilian Octavian) dish enough ham to feed all the empire’s hungry millions; the “Egyptian” costumes for Liz look like they came right off Rodeo Drive; much of the dialogue is thuddingly bad, never more so than when it’s trying to be deep or sophisticated; and there’s absolutely no grace, pace, or subtlety in view anywhere. In truth, the movie has all the swiftness and agility of a three-legged elephant.

Rodeo Drive Cleopatra

Nevertheless, despite four hours and eleven minutes of manifest faults, I’ve always had a sneaking affection for this dinosaur. Hammy acting and risible dialogue provide pleasures of their own (if you didn’t agree you wouldn’t have read this far), Alex North’s score is pleasingly exotic, the great naval battle of Actium is genuinely and unironically spectacular, the film looks terrific (thanks to cinematographer Leon Shamroy), some performers in smaller roles do well, Cleopatra’s death scene is surprisingly understated and effective, and last but not least, looking at Elizabeth Taylor for four hours isn’t exactly hard labor. When you need a good dose of old-time Hollywood excess and SPQR, you could do worse than Cleopatra, and it’s certainly no sillier than eighty hours of wildlings beyond the Wall and winter is coming and valar morghulis. One fantasy mode is about as much fun as the other, and indeed, in most key respects they’re practically identical.

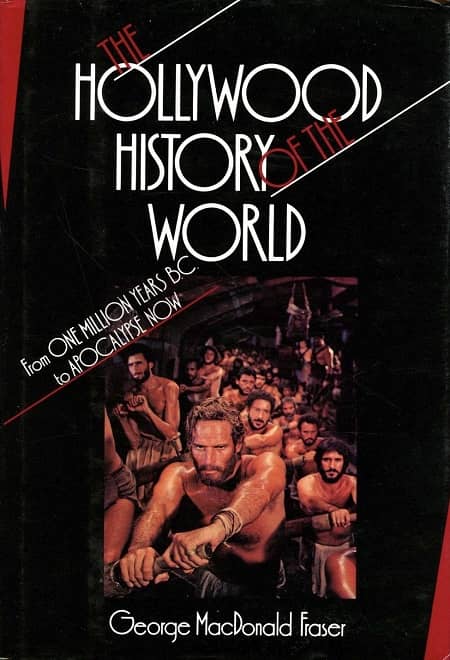

So after Game of Thrones wraps next year and you’re desperately trying to find some way to replicate the gaudy thrills the series pumped into your drab and colorless life, consider giving the old Hollywood historical epics of yesteryear a try. (A great place to find out more about them is The Hollywood History of the World, a lively 1988 book by George MacDonald Fraser, the author of the Flashman novels. Ever the contrarian, Fraser asserts that Hollywood’s general level of historical accuracy is substantially better than is commonly assumed.)

After a wine cooler or three, it may be hard to tell Julius Caesar from Ned Stark, and… wait — what did you say? There’s a prequel Game of Thrones series in the works? The video saga of Westeros isn’t ending — it’s just beginning?

Oh. Well, in that case… never mind.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was A Classic Without the Quotation Marks: Rogue Moon by Algis Budrys.

Me, I’m just sad that de Mille never made a John Carter of Mars film on the scale of The Ten Commandments.

Joe — Wouldn’t that be something!

I don’t know about a DeMille Barsoomian epic, but in the mid seventies, I heard Ray Bradbury speak at the Change of Hobbit bookstore in L.A. and he talked about his desire to see Ray Harryhausen do a Burroughs Martian movie. I certainly would have been on board for that! (When he died, DeMille was making plans for what he said would be his last and greatest film – the story of Baden Powell and the Boy Scouts!)

Yeah, de Mille for the spectacle, Harryhausen for the special effects would be my dream team, I think.