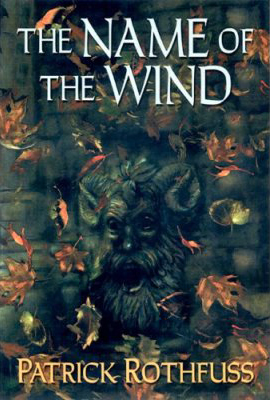

Fiction Review: The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss

A Review by Robert Rhodes

Copyright 2008 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright 2008 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

The Name of the Wind

Patrick Rothfuss

DAW (hardcover, 662 pages, March 2007, $24.95)

“I have stolen princesses back from sleeping barrow kings. I burned down the town of Trebon. I have spent the night with Felurian and left with both my sanity and my life. I was expelled from the University at a younger age than most people are allowed in. I tread paths by moonlight that others fear to speak of during day. I have talked to Gods, loved women, and written songs that make the minstrels weep.

“You may have heard of me.”

With this modest introduction begins the autobiography of the notorious Kvothe (pronounced “quothe”), the flame-haired protagonist of Patrick Rothfuss’ debut novel, The Name of the Wind. At the start of the novel, Kvothe — a young man still — has ended his adventuring days to live incognito as an innkeeper; but when the historian called Chronicler appears, Kvothe accepts the opportunity to provide the definitive account of his deeds — in short, to set the record straight. Kvothe, despite the historian’s skepticism, insists his story will take three days to tell properly, and so opens Day One of The Kingkiller Chronicle.

Kvothe’s youth closely resembles Harry Potter’s: his parents are murdered by a dark wizard of legend, he escapes physically intact, and in seeking answers and power, he enters a school of magic (“the University”) where, among other challenges, he crosses a wealthy rival. But if Name, at its core, is another bildungsroman of a gifted orphan, it is an intricately detailed and often captivating one. (Nor is it a tale for children. Kvothe does not inherit a fortune or journey to the school on an enchanted train; rather, after his parents’ death, he spends years as a street urchin, facing hunger, illness, and frequent danger.)

What distinguishes Name from most fantasy novels — beyond its transparent prose — is the author’s keen intellect, which manifests itself in various ways. Foremost among these is the world’s magic system, which appears to consist of math- and logic-based sympathetic magic and id- and intuition-based “naming” magic. (The latter seems harder to grasp, providing the basis for the novel’s title.) Other manifestations of the author’s talent include clever dialogue; craftsmanship in both first-person narration (Kvothe’s recollections) and third-person (interludes at the inn); a realism-bolstering explanation of a shorthand system that allows Chronicler to record Kvothe word for word; an original fight with a dragon; and two extensive tales-within-the-tale: one historical, one religious — the former Tolkien-esque, the latter Lewisian and possibly as precise an allegory as Aslan’s sacrifice in The Lion, The Witch, & The Wardrobe. Clearly, Mr. Rothfuss has an appreciation and affinity for the tradition of storytelling, as does Kvothe; and through Kvothe, the author slips in a handful of meta-fictional comments as Kvothe reminds his audience (and us) that his story is not a fairy tale.

As well-crafted as Name is, and as extensively as the author worked on it — devoting over seven years to the entire trilogy, according to his website — it’s not perfect. At 662 pages, it felt thirty to sixty pages too long, particularly due to Kvothe’s redundant descriptions of precisely how many coins he owned at certain times and other details (such as eating and haggling) that could have been summarized instead of related word for word. At times, I carried Name around my house, called to chores but fascinated by Kvothe’s spell, but at others, particularly in the late-middle chapters, my eyes kept darting to the next page, searching for a sign that something significant was about to happen. Also, Kvothe’s relationship with his love-interest, Denna, over-relies on coincidental meetings — even though Kvothe remarks on the coincidences — and their interactions seem artificial. They spend evenings together, for example, talking for hours, but never broach the subject of their pasts or Denna’s mysterious disappearances. Lastly in the way of quibbles (kvibbles?), this first installment of the tale lacks an intense, palpable experience of evil. Although the dark wizard and his minions (the Chandrian) slaughter Kvothe’s family (off-stage), their motives remain hidden, and they fail to evoke the shocking malice found, for example, in George R. R. Martin’s A Game of Thrones, where in the opening chapters, the golden knight Jaime Lannister commits adultery, incest, and the attempted murder of a child — from the child’s point of view, no less.

A final comment, neither praise nor quibble: Name is an ambitious undertaking (both by the author and DAW) in that it is far from self-contained. It lacks a traditional climax and leaves numerous plot-threads dangling … albeit skillfully baited by the author. Anyone who requires closure may want to wait until all three parts are out, as this is not the first book of a trilogy (as trilogies have come to be known) as much as the first third of a seamless tale. For now, I would give Name four of five possible stars, withholding the fifth (or the right to take one away, if the quality improbably drops) until Kvothe’s tale, past and present, is complete.

Recommended without reservation for fans of Robin Hobb (Assassin’s Apprentice), Gene Wolfe (The Shadow of the Torturer), and Neil Gaiman (Stardust), as well as mature students who are graduating from Harry Potter. A highly promising debut.