A Tale of Wonder: The Last Unicorn by Peter Beagle

When Molly Grue yells at the unicorn, it expresses a little how I felt on reading Peter Beagle’s The Last Unicorn (1968) this past month for the very first time:

But Molly pushed him aside and went up to the unicorn, scolding her as though she were a strayed milk cow. “Where have you been?” Before the whiteness and the shining horn, Molly shrank to a shrilling beetle, but this time it was the unicorn’s old dark eyes that looked down.

“I am here now,” she said at last.

Molly laughed with her lips flat. “And what good is it to me that you’re here now? Where were you twenty years ago, ten years ago? How dare you, how dare you come to me now, when I am this?” With a flap of her hand she summed herself up: barren face, desert eyes, and yellowing heart. “I wish you had never come, why do you come now?” The tears began to slide down the sides of her nose.

Of course, what Molly learns is that she needn’t have waited for wonder and transcendence to find her, but should instead have sought them. Taking her lesson to heart for myself, I felt betrayed and angry for only a moment before yielding to chagrin that I hadn’t sooner sought this perfectly-cut gem of a story. The book sat on a shelf for twenty years, gathering dust and losing to the sun the richness of color of its wonderful Gervasio Gallardo artwork.

If The Last Unicorn was a lesser book, I could offhandedly describe it as an illustration of the universal need to undertake a quest, to find wonder — whether from beauty or love or something more ineffable. But Beagle has given us so much more. He’s tucked treasures inside prose that echoes with the sounds of hidden woodland glens and that is painted in the colors of lost and recovered dreams; he’s elucidated the value that can be gleaned from loss, sacrifice, regret. And further, he’s told a story about stories, and how they don’t reflect reality, except when they do. He’s played with the various elements of fantasy — the quest, the wizard, the princess, etc. — in a way that loves them as much as it punctures them.

The unicorn lived in a lilac wood, and she lived all alone. She was very old, though she did not know it, and she was no longer the careless color of sea foam, but rather the color of snow falling on a moonlit night. But her eyes were still clear and unwearied, and she still moved like a shadow on the sea.

She did not look anything like a horned horse, as unicorns are often pictured, being smaller and cloven-hoofed, and possessing that oldest, wildest grace that horses have never had, that deer have only in a shy, thin imitation and goats in dancing mockery. Her neck was long and slender, making her head seem smaller than it was, and the mane that fell almost to the middle of her back was as soft as dandelion fluff and as fine as cirrus. She had pointed ears and thin legs, with feathers of white hair at the ankles; and the long horn above her eyes shone and shivered with its own seashell light even in the deepest midnight. She had killed dragons with it, and healed a king whose poisoned wound would not close, and knocked down ripe chestnuts for bear cubs.

Unicorns are immortal. It is their nature to live alone in one place: usually a forest where there is a pool clear enough for them to see themselves — for they are a little vain, knowing themselves to be the most beautiful creatures in all the world, and magic besides. They mate very rarely, and no place is more enchanted than one where a unicorn has been born. The last time she had seen another unicorn the young virgins who still came seeking her now and then had called to her in a different tongue; but then, she had no idea of months and years and centuries, or even of seasons. It was always spring in her forest, because she lived there, and she wandered all day among the great beech trees, keeping watch over the animals that lived in the ground and under bushes, in nests and caves, earths and treetops. Generation after generation, wolves and rabbits alike, they hunted and loved and had children and died, and as the unicorn did none of these things, she never grew tired of watching them.

This lyrical novel tells of the search by the titular character for the rest of her kind. Unbeknownst to her until she overhears a pair of hunters talking, all the other unicorns in the world have vanished. For the very first time, she ventures out of the confines of her “lilac wood” and begins a search for her kin. She quickly realizes humans don’t perceive her real nature, seeing instead only a beautiful white mare, which they try — and fail — to capture. It’s when she meets a song lyric-quoting butterfly who knows what she really is that she gets a clue to what happened to the rest of the unicorns:

“Please,” she said. “All I want to know is that there are other unicorns somewhere in the world. Butterfly, tell me that there are still others like me, and I will believe you and go home to my forest. I have been away so long, and I said that I would come back soon.”

“Over the mountains of the moon,” the butterfly began, “down the Valley of the Shadow, ride, boldly ride.” Then he stopped suddenly and said in a strange voice, “No, no, listen, don’t listen to me, listen. You can find your people if you are brave. They passed down all the roads long ago, and the Red Bull ran close behind them and covered their footprints. Let nothing you dismay, but don’t be half-safe.” His wings brushed against the unicorn’s skin.

“The Red Bull?” she asked. “What is the Red Bull?”

The butterfly started to sing. “Follow me down. Follow me down. Follow me down. Follow me down.” But then he shook his head wildly and recited, “His firstling bull has majesty, and his horns are the horns of a wild ox. With them he shall push the peoples, all of them, to the ends of the earth. Listen, listen, listen quickly.”

“I am listening,” the unicorn cried. “Where are my people, and what is the Red Bull?”

Unwilling, or unable, to tell her more, he flits off.

Continuing on her way, she is captured by Mommy Fortuna, witch and carnival owner. From the witch, she learns the Red Bull is connected to King Haggard. She is later rescued by one of Fortuna’s employees, Schmendrick the Magician. As his name, Yiddish slang for a bumbler, indicates, he is less than competent at his trade. He insists that in payment, the unicorn must allow him to help her find the other unicorns. Later the pair are joined by Molly Grue, wife of a third-rate woodland bandit named Captain Cully. From this point on, The Last Unicorn is as much the two humans’ story as it is the unicorn’s. Together the three set off in search of King Haggard’s kingdom; the land of the Red Bull.

While The Last Unicorn is truly a work of beautifully written, deep and thoughtful prose, much more than fable, still its message that seeking wonder — and wonder is all around you! — rings out across the entire book. A yearning for wonder is something everyone has and needs. Unable to ever truly appreciate the beauty and marvels around him has made King Haggard covetous, bitter, and cruel. Molly, briefly angry for what she missed out on in her youth, now cleaves to the unicorn in middle age and it restores and revives her soul in unexpected ways. And given the chance to escape their grubby lives and grubby criminality, Captain Cully’s band of outlaws race after an illusion invoked by Schmendrick:

Effortlessly proud, graceful as giraffes (even the tallest among them, a kind-eyed Blunderbore), the bowmen moved across the clearing. Last, hand in hand, came a man and a woman. Their faces were as beautiful as though they had never known fear. The woman’s heavy hair shone with a secret, like a cloud that hides the moon.

“Oh,” said Molly Grue. “Marian.”

“Robin Hood is a myth,” Captain Cully said nervously, “a classic example of the heroic folk-figure synthesized out of need. John Henry is another. Men have to have heroes, but no man can ever be as big as the need, and so a legend grows around a grain of truth, like a pearl. Not that it isn’t a remarkable trick, of course.”

It was the seedy dandy Dick Fancy who moved first. All the figures but the last two had passed into the darkness when he rushed after them, calling hoarsely, “Robin, Robin, Mr. Hood sir, wait for me!” Neither the man nor the woman turned, but every man of Cully’s band — saving only Jack Jingly and the captain himself — ran to the clearing’s edge, tripping and trampling one another, kicking the fire so that the clearing churned with shadows. “Robin!” they shouted; and “Marian, Scarlet, Little John — come back! Come back!” Schmendrick began to laugh, tenderly and helplessly.

Over their voices, Captain Cully screamed, “Fools, fools and children! It was a lie, like all magic! There is no such person as Robin Hood!” But the outlaws, wild with loss, went crashing into the woods after the shining archers, stumbling over logs, falling through thorn bushes, wailing hungrily as they ran.

Only Molly Grue stopped and looked back. Her face was burning white.

“Nay, Cully, you have it backward,” she called to him. “There’s no such a person as you, or me, or any of us. Robin and Marian are real, and we are the legend!” Then she ran on, crying, “Wait, wait!” like the others, leaving Captain Cully and Jack Jingly to stand in the trampled firelight and listen to the magician’s laughter.

Peter Beagle has said that Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows had a great impact on him becoming a writer. In that book, Mole breaks out of his normal life, summoned to something new by “joy of living and the delight of spring without its cleaning.” There’s much of that same feeling to The Last Unicorn. The whole book is like spring, calling the reader through the characters to experience the world’s marvels. There are dangers and hazards aplenty for the unicorn, Schmendrick, and Molly, but the case for living life with all its delights as well as its melancholies is strong.

There are so many wonderful things about Beagle’s book. I particularly love his almost contempt for any effort to tell a standard genre story. There are no maps, magic systems, or lexicons filling the back of the book. Anachronisms litter the story, from the butterfly quoting “(Won’t You Come Home) Bill Bailey” to Haggard’s armor made of bottlecaps. Characters know that they are in a story, with all the demands it and the audience makes of them. Things need to be done in a certain way if they are to be True. And still, Beagle loves his characters and believes they can do good in the face of selfishness and danger.

The Last Unicorn is like a painting by Richard Dadd, wildly fanciful and full of minute details. Strange things lurk in the shadows and behind the trees. The prose is by turns beautiful, delightful, and elegiac. Wistfulness, poignant loss, humor, and fear all hold an equal place in Beagle’s novel. The characters, variations on familiar archetypes, are painted with colorful depth and sympathy, especially Schmendrick and Molly. Even the wretched King Haggard invites a bit of sympathy. If, like me, you’ve foolishly allowed this extraordinarily beautiful little book to escape your attention, find a copy and let it capture you for a few days.

Peter Beagle wrote his first novel, A Fine and Private Place (1960), when he was 19. Between then and 1968 he worked on ideas that eventually became The Last Unicorn. Since then he’s written several stories, including the Hugo- and Nebula-winning “Two Hearts”, concerning the characters of The Last Unicorn.

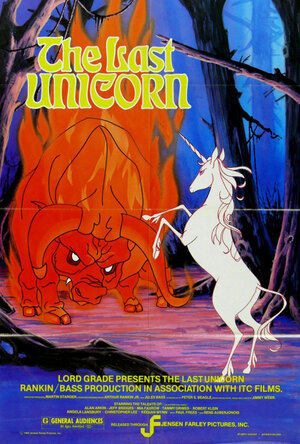

The Last Unicorn was also made into an animated film in 1982. A Rankin-Bass production, Beagle wrote the screenplay and the animation was done by people who went on to make up part of the original Studio Ghibli team. Its cast includes Alan Arkin, Mia Farrow, Tammy Grimes, and Christopher Lee, among many other outstanding actors. I could do without most of Jimmy Webb’s songs as performed by America, but they don’t ruin what’s a good, and often frightening and moving, movie.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

As a fan of both book and movie, I would recommend “Two Hearts”, Mr. Beagle’s “coda” to The Last Unicorn. It is readable on his website. Careful, though, it is heart-breaking.

It’s a great book, especially as it blends disparate elements that you wouldn’t think would work together. The only book that I can think of that does the same kind of balancing act is John Bellairs’ shamefully neglected The Face in the Frost.

@Thomas – Thank you – Face in the Frost is a book to add to my list. I read it only once decades ago and it definitely fits the criteria for this series. Also – The Once and Future King (which I might reread) – does some of this, though not as much

@Eugene – Thank you, I’ve wanted to read it, but I’ll be prepared.

This sounds remarkably similar to my experience — I bought a copy of the book sometime in the 1990s, I think, and didn’t actually read it until 20+ years later, at which point I proceeded to start kicking myself for not having read it sooner.

@Joe H – I used to get angrier about that, but now, I just try to relish the fact I’ve finally come to something remarkable

I first read this when I was a teenager, back in the 70s and loved it. I was working my way through any Ballantine Adult Fantasy I could get hold of that time and only about a third of the whole series was published over on my side of the pond. What struck me most was the comedy. Fantasy always seemed to be about serious things – people being called in to sort out big problems and getting rewarded with kingdoms to rule; or people not getting rewarded and ending up dead or worse! Beagle’s novel has some serious themes but it is also very funny. I read it again a few years back and did not find it as funny. I was in my fifties and, in any case, remembered many of the jokes but I loved the book for the more serious issues it faced. I read A Fine and Private Place at around the same time and found that funnier but also very moving. You seem to be covering all those classics that I read as a teenager. Please keep going!

@Neilh – Glad to oblige! I can only imagine how this would have seemed to me as a teenager. I suspect I would have focused on the funny bits more as well.

I read the book soon after it was published, reading parts of it in High School Forensics competition in 1969 and 1970. I have never seen the film (thought it must have been disneyfied), but will do so now that I read that Beagle wrote the screen play. Cant wait to read “Two Hearts”?