The Death and Legacy of Robert Jordan

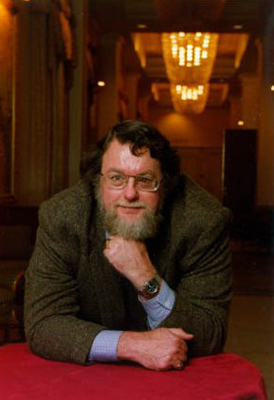

James Oliver Rigney, Jr. (1948-2007)

By Leo Grin

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

When bestselling author Robert Jordan died on September 16, 2007, it formed the second loss in as many years of a fantasy writer notable for an extreme prolificacy not only of words but of fans (David Gemmell, author of nearly thirty popular books in the field, died July 28 last year, also coincidentally of heart trouble.) Both authors can be said to have left us far before their time, in the primes of their careers, and both left behind popular unfinished series (Gemmell’s Troy trilogy, and of course Jordan’s Wheel of Time saga).

When bestselling author Robert Jordan died on September 16, 2007, it formed the second loss in as many years of a fantasy writer notable for an extreme prolificacy not only of words but of fans (David Gemmell, author of nearly thirty popular books in the field, died July 28 last year, also coincidentally of heart trouble.) Both authors can be said to have left us far before their time, in the primes of their careers, and both left behind popular unfinished series (Gemmell’s Troy trilogy, and of course Jordan’s Wheel of Time saga).

Unfortunately, the two authors share another sad trait: as memorials popped up from Jordan’s friends and admirers, other corners of fandom, large corners, maintained a curious silence. For Jordan and Gemmell were popular writers, to a degree that breeds equal parts jealousy and critical scorn among elites. “If it sells, it’s lightweight as hell,” the saying might go, and if fans are waiting for awards committees and New York publishing cliques to consider these losses on a literary level, they’ll be waiting a long time. We can expect the eventual (and, it is to be hoped, long-in-coming) demises of critical darlings like Le Guin or Ligotti to produce rapturous levels of grief and analysis, but the attention accorded the literati’s golden geese seldom trickles down (up?) to the much more successful ganders whose books litter the shelves of the S&S hoi polloi. Last year at the World Fantasy Convention, my friend Steve Tompkins felt it necessary to attend the annual memorial panel and speak up on Gemmell’s behalf, fearing that — without his stentorian voice offering some words of remembrance — Gemmell would fail to be spoken of in a positive light, if at all. Consider that the Englishman has sold well in excess of ten million books, and Steve’s worry becomes worth lamenting and, to the best of our ability, eradicating.

Robert Jordan’s legacy carries even more of a love-him-or-hate-him dynamic to it. Gemmell had many completed series and story arcs to his name, and his final trilogy was painfully close to beng finished (and will, in fact, be completed by his wife, who had collaborated on the earlier Troy novels and is working from Gemmell’s 70,000 word first draft and prodigious story notes). But Jordan’s one gargantuan contribution to the field has now been left ending with a monolithic ellipsis, a towering “Never To Be Continued” blinking forlornly in front of readers who have steadily read the tale for much of their adult lives. What’s to be made of this situation, and the striking author whose strange, unpredictable career brought it about? As years pass and the genre continues its slow continental drift towards places unknown, what will be the final, enduring judgment on this staggeringly successful man and his cruelly aborted masterpiece?

Robert Jordan’s legacy carries even more of a love-him-or-hate-him dynamic to it. Gemmell had many completed series and story arcs to his name, and his final trilogy was painfully close to beng finished (and will, in fact, be completed by his wife, who had collaborated on the earlier Troy novels and is working from Gemmell’s 70,000 word first draft and prodigious story notes). But Jordan’s one gargantuan contribution to the field has now been left ending with a monolithic ellipsis, a towering “Never To Be Continued” blinking forlornly in front of readers who have steadily read the tale for much of their adult lives. What’s to be made of this situation, and the striking author whose strange, unpredictable career brought it about? As years pass and the genre continues its slow continental drift towards places unknown, what will be the final, enduring judgment on this staggeringly successful man and his cruelly aborted masterpiece?

That Jordan made one hell of an impression goes without saying. A thriving genre needs all kinds of writers to keep it rumbling along in the marketplace of ideas. Jordan brought fantasy much needed attention and sales at a time when the old publishing booms had dwindled, and alternate art forms like movies and RPGs were writhing in an existential crisis. TSR and D&D were floundering, TV shows like Hercules and Xena winked and joked their way through virtual parodies of serious fantasy classics, and a host of promising fantasy authors (Karl Edward Wagner, Charles Saunders, David C. Smith) had fallen off the map, largely replaced by drear and maudlin Druidic and Wiccan fantasy as exemplified by Robert Holdstock’s Mythago Wood. Jordan hit the marketplace with the colorful, ersatz vigor of the film American Graffiti, which brought the ’50s roaring back to popularity in the face of Vietnam and Watergate jadedness.

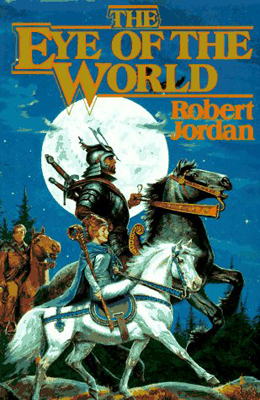

Jordan seemed for awhile as if he would bridge the gap between the Howard/Tolkien era and whatever modern fantasy was becoming, sort of like a more original version of Terry Brooks (another hugely successful author, but one who has never quite lived down his early slavish emulation of the Tolkien template). Jordan’s major role in the Conan deluge of the 1980s had many fans believing that he not only created Robert E. Howard’s most famous character, but that his Conan novels were merely a prelude to something more grand. When The Eye of the World debuted, garden-variety fans predicted that Jordan was on the cusp of creating the Next Big Thing. His was the first fantasy series of my post-teen years to regularly hit not only genre lists but the main fiction bestseller lists. I remember being somewhat amazed that he did it not with a fantasy more societally and critically palatable, like Watership Down or Jonathan Livingston Seagull, but rather with a long, ongoing series of unapologetic invented-world fantasy books that hearkened as much to role-playing sensibilities as to anything else. It was a watershed of sorts — D&D geek fantasy gone mainstream.

Jordan seemed for awhile as if he would bridge the gap between the Howard/Tolkien era and whatever modern fantasy was becoming, sort of like a more original version of Terry Brooks (another hugely successful author, but one who has never quite lived down his early slavish emulation of the Tolkien template). Jordan’s major role in the Conan deluge of the 1980s had many fans believing that he not only created Robert E. Howard’s most famous character, but that his Conan novels were merely a prelude to something more grand. When The Eye of the World debuted, garden-variety fans predicted that Jordan was on the cusp of creating the Next Big Thing. His was the first fantasy series of my post-teen years to regularly hit not only genre lists but the main fiction bestseller lists. I remember being somewhat amazed that he did it not with a fantasy more societally and critically palatable, like Watership Down or Jonathan Livingston Seagull, but rather with a long, ongoing series of unapologetic invented-world fantasy books that hearkened as much to role-playing sensibilities as to anything else. It was a watershed of sorts — D&D geek fantasy gone mainstream.

Ultimately he took the fantasy saga to — well, not so much new heights as new lengths, and his success at that endeavor was itself enormously influential in the field. A sizable wake of other authors owe their careers to the success of The Wheel of Time, as publishers scrambled to sign up gals and gents who strove to replicate the appeal of Jordan’s complex, sprawling, wordy, byzantine, endless masterwork.

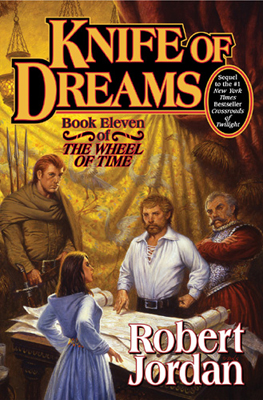

The Wheel of Time is a curious beast, filled with massive helpings of (to my mind) laudable poetic imagery of a sort missing from far too many of his contemporaries, who for the most part just narrate plot. Publisher’s Weekly gave his most recent book, Knife of Dreams, a starred review, and praised “the breakneck pace, lyrical beauty and astonishing scope” of the series. I can agree with that — at his best, Jordan had a sizable talent for the windswept vistas and sunset-haloed imagery that makes good epic fantasy a joy to read. But too often you get the feeling he’s not quite in command of the conjured images, not writing from inner sight. Rather, he’s hopscotching deftly across a landscape of cliches, names, and images pioneered by better writers. After a Prologue, the first book begins thusly:

The Wheel of Time is a curious beast, filled with massive helpings of (to my mind) laudable poetic imagery of a sort missing from far too many of his contemporaries, who for the most part just narrate plot. Publisher’s Weekly gave his most recent book, Knife of Dreams, a starred review, and praised “the breakneck pace, lyrical beauty and astonishing scope” of the series. I can agree with that — at his best, Jordan had a sizable talent for the windswept vistas and sunset-haloed imagery that makes good epic fantasy a joy to read. But too often you get the feeling he’s not quite in command of the conjured images, not writing from inner sight. Rather, he’s hopscotching deftly across a landscape of cliches, names, and images pioneered by better writers. After a Prologue, the first book begins thusly:

The Wheel of Time turns, and Ages come and pass, leaving memories that become legend. Legend fades to myth, and even myth is long forgotten when the Age that gave it birth comes again. In one Age, called the Third Age by some, an Age yet to come, an Age long past, a wind rose in the Mountains of Mist. The wind was not the beginning. There are neither beginnings nor endings to the turning of the Wheel of Time. But it was a beginning.

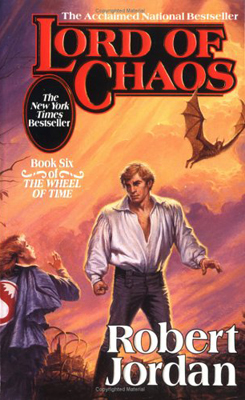

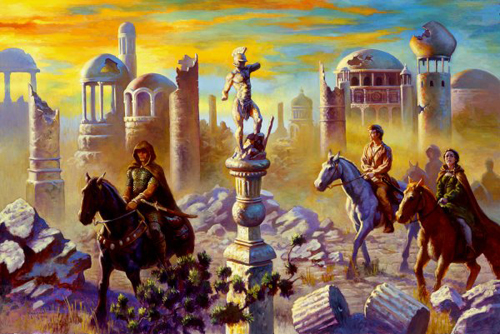

It’s enough to make your head spin, and yet you can’t help but hope that anyone sharing such a fondness and respect for the evocation of third ages and misty mountains will eventually move beyond such circuitous wordsmithing and strike out to places unknown but clearly his own. Alas, Jordan was much more fond of beginnings than endings, and thus what began as The Lord of the Rings, American Style ended up as a Long March The Bold and the Beautiful for Magic: The Gathering fans, fantasy’s answer to the soap opera (something which became increasingly apparent in the cover art — compare the martial, chivalric, mystical quest imagery on The Eye of the World to the near Fabio-esque allure of Lord of Chaos).

Much like Steven King’s decades-long affair with his Gunslinger Septology, The Wheel of Time started out as a strange mix of the off-kilter and the pleasantly derivative, then picked up steam through the middle books and gained a legion of fans who believed. They believed most of all that, despite looming portents, he would somehow manage to wrangle and wrap-up the hundreds of plot points and story arcs that had replicated across his fantasy world like tribbles. Then, in excruciating slow motion, each series careened off the rails in stunning fashion, ending as prose train wrecks of heartbreaking scope.

With King, Wolves of the Calla was the first hint that something was threatening to go horribly awry, a quiet, creeping dread that The Song of Susannah soon confirmed with an apocalyptic thunderclap of bad artistic decisions. The series, worked on for his entire professional life, was his attempt at creating something with the mythic weight and heft of a Lord of the Rings. He had led readers through a promising beginning, then teased them across long years of sporadic but intriguing releases with the skill of a Gypsy Rose Lee. Holding off for so long was a gutsy move — we’ll never know how many thousands of readers died, literally died, waiting for King to cease the pretentious build-up and get on with it. Each book raised expectations for the final volume’s ultimate revelations, putting ever more chips on the line. “Stick with me, kids,” King seemed to promise, “the payoff is going to be huge.”

And then, poof. In a trice, King’s plot had spun out of his grasp. First, he destroyed his classic, near-mythic conception of vampires with an extended Calla-and-Susannah sidebar featuring Salem Lot‘s Father Callahan, one that inflicted on Lot fans the same wound that George Lucas’ new “it’s all in the blood” explanations did to his previous cosmic, quasi-religious conception of The Force. As fans screamed in dismay King went even further down the road of hubris, taking the astoundingly destructive step of writing himself into The Dark Tower series as a major character, blurring the line between authorship and reality. Yep, just like the cowboys at the end of the film Blazing Saddles, who suddenly ride out of the authentic West and appear in a movie studio, tearing through the “fourth wall” of moviemaking to hilarious effect. Finally, he wrote an ending that ranks as one of the all-time cop-outs, the literary equivalent of those “sucker boxes” mischievous boys used to place on roads (the joke being that a driver would be forced to stop, get out of the car, trudge over to the box, pick it up…and then see a note on the ground saying, “Please leave this box in the road for the next sucker.”) What a cosmic gyp to slog through seven padded and overwritten books over twenty-two years, only to discover that King’s plot has no real beginning or ending, that it was just one long, meaningless circle jerk that ended with the publishing equivalent of “Leave this series on the shelf for the next sucker.” The fans, and to an extent King’s sales and goodwill, never recovered.

And then, poof. In a trice, King’s plot had spun out of his grasp. First, he destroyed his classic, near-mythic conception of vampires with an extended Calla-and-Susannah sidebar featuring Salem Lot‘s Father Callahan, one that inflicted on Lot fans the same wound that George Lucas’ new “it’s all in the blood” explanations did to his previous cosmic, quasi-religious conception of The Force. As fans screamed in dismay King went even further down the road of hubris, taking the astoundingly destructive step of writing himself into The Dark Tower series as a major character, blurring the line between authorship and reality. Yep, just like the cowboys at the end of the film Blazing Saddles, who suddenly ride out of the authentic West and appear in a movie studio, tearing through the “fourth wall” of moviemaking to hilarious effect. Finally, he wrote an ending that ranks as one of the all-time cop-outs, the literary equivalent of those “sucker boxes” mischievous boys used to place on roads (the joke being that a driver would be forced to stop, get out of the car, trudge over to the box, pick it up…and then see a note on the ground saying, “Please leave this box in the road for the next sucker.”) What a cosmic gyp to slog through seven padded and overwritten books over twenty-two years, only to discover that King’s plot has no real beginning or ending, that it was just one long, meaningless circle jerk that ended with the publishing equivalent of “Leave this series on the shelf for the next sucker.” The fans, and to an extent King’s sales and goodwill, never recovered.

Jordan stretched his ambitious tale even further, to a dozen books, until it was not just a Dark Tower but a literary Tower of Babel possessing all of the attendant frenzied hubris such an analogy demands. Like King, it was Jordan’s fifth book, The Fires of Heaven, that began to betray the creeping bloat and drag that would be his undoing. These early warning signs bloomed to full flower in the successor volume Lord of Chaos, and after that The Wheel of Time began to leak and wobble on its axle. No excuse the fans devised for it and themselves could save them from the spectacle of a precious and elaborate house of cards crashing down before their eyes. Here, courtesy of Amazon, is an all-too typical review that succinctly expresses the frustration and almost physical harm fans felt:

I started reading this series when I was in college. I have since been through medical school, residency, and have been working for several years. I regret that I ever picked up the first book. I enjoyed the first three books, but always anticipated a grand finale that never came. Somewhere after the fifth book, I quit. No longer could I bear to hear about a female character tugging at her hair when she was angry or other such interminably repeated mannerisms. Because of this series, I promised myself I would never start a series that had not already been completed. In fact, I was so disappointed in the time I had wasted in reading these books, that I have read little fiction since. Let my experience serve as a warning to you: don’t start this series until it is done and you know from others that it is worth the investment of time and money. I suspect the series will never be really done…

Sadly, the dreadful wyrd that had haunted a generation of Jordanaires — that the series would remain unfinished — has now come to pass. They are left with the bitter realization that an enormous emotional investment has been sunk into the literary equivalent of a bankrupt hedge fund. I suppose that Jordan may well become the next V. C. Andrews, with ghost writers continuing the series under his name indefinitely — he certainly left enough false leads and tag ends blowing in the wind with which to work (indeed, there are rumors that his family has enough notes and instructions with which to complete the final volume in some form). And I can’t help but think that any reader with so little literary discernment that he or she blithely trudged through the first eleven novels in The Wheel of Time — thousands of pages of which all but his staunchest fans judged to be interminable — will have any reason to stop now. Like the guys who read all the Conan pastiches and try with grim seriousness to place them into a logical timeline, there’s little fear that they would even realize that another hand had picked up the flag and was marching forward with it.

If we must delineate Robert Jordan’s legacy in the field, it is that his imperial overstretch conquered wilderness and paved roads that other authors now travel, writers eager to establish literary empires of more glory and permanence. He was a trailblazer and a builder, and if what he left seems to lack the artistry of a Howard or a Tolkien, well, the world needs double-wides and tract homes, too. If he wasn’t a Isidore of Miletus or even a Frank Lloyd Wright, it seems increasingly likely he’ll be remembered as a Sarah Winchester, and that has its own charm. Godspeed, Robert Jordan.

Brandon Sanderson has entered the chat