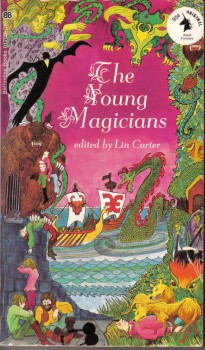

The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series: The Young Magicians edited by Lin Carter

The Young Magicians

The Young Magicians

Lin Carter, ed.

Ballantine Books

October 1969, 280p. $0.95

Cover art by Sheryl Slavitt

I apologize for having taken so long to get this post done. I’ve been on the road for over half the weekends since the end of April, mostly family trips for graduations or dive meets my son was competing in. I thought I would have a little more time when the second summer session started since I would be teaching, but that hasn’t exactly been the case. (No, I have no idea why I would have thought that.)

But I’m back, and I would like to thank John for his patience. I’m tanned; I’m rested; I’m ready. Well, I’m tanned at any rate. And I’ve got a pretty darned good anthology to tell you about.

A number of people, myself included, have said that Lin Carter’s legacy will ultimately not be his writing or his Conan pastiches, but the work he did on the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. It’s hard in this day and age of ebooks and specialty presses to remember how hard fantasy was to find on bookstore shelves in the late 1960s. The commercial fantasy boom wasn’t far off, but it hadn’t gotten there. It was possible to read just about all of the titles that were easily available at the time.

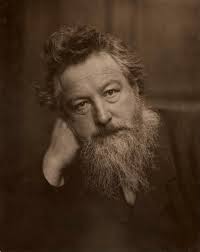

The Young Magicians was a companion volume to Dragons, Elves, and Heroes with both of them being published in October 1969. That volume contained examples of imaginary world fantasy beginning with folktales and sagas and ending with William Morris. In The Young Magicians, Carter starts with Morris and provides samples of fantasy from more contemporary writers, ending with Lin Carter himself.

The Morris selection here is a poetic version of “Rapunzel”. This isn’t a prose poem, rather it’s broken into stanzas, with the Prince, the Witch, and Rapunzel each having multiple speaking parts. Reading this reminded me that there is a rhythm and a cadence to Morris’s prose, and if you can find the cadence, then he can be quite enjoyable.

Lord Dunsany is represented with “The Sword of Welleran” It’s the story of a city beset by barbarians. The only thing keeping them from attacking is a ruse pulled by the inhabitants. The heroes who once protected the city, led by Welleran, have all died, but the citizens have an elaborate system of statues which give the appearance of live men riding horses about the walls at night. Then the barbarians really do attack. One young man takes up the titular sword of Welleran and tries to save the city.

E. R. Eddison is represented by a brief excerpt from his Viking novel Styrbiorn the Strong. “In Valhalla” is brief and concerns a Valkyrie asking Odin why he chose to take her favored champion. Eddison had been published by Ballantine before the BAF series started with four novels: The Worm Ouroboros, Mistress of Mistresses, A Fish Dinner in Memison, and The Mezentian Gate. These were later reprinted under the BAF imprint with the unicorn Colophon. These novels were discussed not too long ago here and here.

Of course Carter couldn’t resist including some James Branch Cabell. “The Way of Ecben”, excerpted from The Witch Woman, was a slog. It concerned a king who, after fighting a major war for the hand of a woman, walks away from her and his throne because he was warned about her in a dream. This is the longest story in the book. I found it lacking in the wit and innuendo that the two Cabell volumes I’ve read so far in this series.

Next are a pair of brief tales by Lovecraft, “The Quest of Iranon” and “The Cats of Uthar”. These would later be included in a later BAF volume of Lovecraft’s fiction, The Doom That Came to Sarnath. Neither are what I would consider heroic fantasy, but they certainly qualify as imaginary world fantasy.

As does “The Maze of Maal Dweb” by Clark Ashton Smith, being part of his Xiccarph sequence. This is a downer of a tale a warrior who attempts to rescue his beloved from the clutches of an evil sorcerer.

Carter includes the first of two of his own works, a Dunsany-esque little piece about what happens when a people decide to create their own god in “The Whelming of Oom”.

One of the most popular fantasy authors of the 1920s and 1930s was Abraham Merritt, who wrote under the byline of A. Merritt. (For more on Merritt, see this post.) Merritt specialized in the lost world story, much like H. Rider Haggard did in the previous century. “The Dragon Glass”, though, is one of the few imaginary world stories he wrote. Reading it, I could see why Merritt was so popular in his day. His lush prose painted some beautiful images about a land accessed through the mirror of the title. I am definitely going to try to fit some Merritt into my reading. I could also see why he’s fallen into obscurity. His prose is lush (like I said), and his style old fashioned. Most modern readers probably wouldn’t have the patience for him.

Robert E. Howard had more series characters that most people realize. In addition to the better known Conan, Kull, Solomon Kane, and Bran Mak Morn, there was also James Allison. Allison is crippled, but he remembers past lives when he was a hero in time before recorded history began in a handful of stories. In “The Valley of the Worm” a member of a ferocious tribe slays a monster that can best be described as a huge worm.

After a brief poem by L. Sprague de Camp (“Heldendammerung”), we come to my favorite writer in the field, Henry Kuttner. A protégé of Ray Bradbury, Kuttner penned a handful of sword and sorcery tales to fill the void left by Howard’s death. There were four stories about Elak, a prince of Atlantis, and two concerning Prince Raynor of Sardopolis, a forgotten city in Asia. While not up to the level of Howard’s work, these were entertaining tales. I thought the Prince Raynor stories showed a greater maturity on the part of Kuttner as a writer and wish he had written more. This one concerns the god Pan and curse on a city. (I discuss this one at length here.)

L. Sprague de Camp returns with a story from his Pusadian stories, a world in which Atlantis hasn’t sunk. “Ka the Appalling” is another story about some rogues who get tired of robbing temples and decide to create their own religion. It’s great fun. I enjoyed this story enough to order a second hand copy of what I think is a collection of these stories online.

Jack Vance takes us to his Dying Earth in “Turjan of Miir”. A sorcerer is trying to create artificial people in his lab without success, so he seeks help from an older sorcerer. Of course this help comes with a price and some unforeseen consequences.

C. S. Lewis and J. R. R. Tolkien are represented by poems. Lewis’s concern Narnia. Tolkien was still alive with The Young Magicians was published. He and Carter knew each other, and Tolkien sent him two poems especially for the book, where they appeared for the first time in America.

Before he ended the anthology with a list of recommended reading, he included one of his own works. “Azlon” is an excerpt from a longer work that was unfinished at the time, Khymyrium. I’d not read any of Carter’s original fiction until I read this book, but I’d heard mixed opinions on its quality, with the general consensus being less than positive.. I found, somewhat to my surprise, that I quite enjoyed both selections.

So how does The Young Magicians stack up nearly 46 years after it first appeared? Quite well, the Cabell selection notwithstanding. Most of the stories are written in a modern enough style that most contemporary readers shouldn’t have to work too hard to enjoy them. Carter chose his selections well. Each tale highlights the author’s strengths and gives a potential reader a good idea of what each author’s longer works will be like.

Obviously I liked the Howard and Kuttner stories, both authors being in my top five favorite authors. But the others were all entertaining, with the one aforementioned exception. This is one you should read if you get a chance. It’s the type of book you would dip into from time to time when you want something different from most of the contemporary offerings on the shelf or online. The Young Magicians isn’t one of the most collectible titles in the BAF line, so second hand copies can be found for less than a new paperback.

Obviously I liked the Howard and Kuttner stories, both authors being in my top five favorite authors. But the others were all entertaining, with the one aforementioned exception. This is one you should read if you get a chance. It’s the type of book you would dip into from time to time when you want something different from most of the contemporary offerings on the shelf or online. The Young Magicians isn’t one of the most collectible titles in the BAF line, so second hand copies can be found for less than a new paperback.

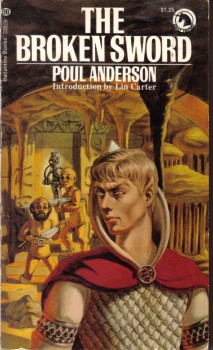

I’m going to skip ahead for my next selection and read Poul Anderson’s The Broken Sword. I’ve got a project in mind that I’ll explain more about in my next post.

Join me, won’t you?

Recent posts in this series are:

Lin Carter and the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series

Lilith by George MacDonald

The Silver Stallion by James Branch Cabell

The Sorcerer’s Ship by Hannes Bok

Deryni Rising by Katherine Kurtz

Land of Unreason by Fletcher Pratt and L. Sprague de Camp

The Doom that Came to Sarnath by H. P. Lovecraft

The Spawn of Cthulhu edited by Lin Carter

Lud-in-the-Mist by Hope Mirrlees

Figures of Earth by James Branch Cabell

Dragons, Elve and Heroes, ed. by Lin Carter

Keith West blogs way more than any sane person should. His main blog is Adventures Fantastic, which focuses on fantasy and historic fiction.

Lin Carter started my love for fantasy in general and sword and sorcery in particular.

I got my hands on his years best fantasy series he did for DAW (I miss those yellow spines) as young teenager. The stories fired my imagination. I thought all fantasy was like that. I was disappointed when a new editor took over the series.

Anyway I will always have a fondness for Lin Carter as an author, editor and ambassador for fantasy, weird and pulp fiction.

Well said, Charles. Although I think Arthur Saha did the best job he could, following in Carter’s footsteps.

Charles and John, I didn’t start reading the series until Saha had taken over. Carter was a year or two before my time. I enjoyed both series, although the men did have different tastes.

[…] got a new BAF post up at Black […]

I think I bought this one, as a kid of 14, when it first came out on the paperback racks. The Lewis and Tolkien items were highlights for me, but I was provoked to interest in most of the other authors.

The book is of its time, when publishers sometimes didn’t distinguish high fantasy from pulp fantasy/sword and sorcery. At least, sword and sorcery paperbacks could be sold with comparison to Tolkien:

http://tolkienandfantasy.blogspot.com/2011/07/pre-1970-paperbacks-with-comparisons-to.html

http://tolkienandfantasy.blogspot.com/2011/11/dale-nelsons-summation-on-tolkien-in.html

The Young Magicians was, for Americans, a glimpse of Tolkien’s creativity that was the newest thing, I suppose, since 1967’s The Road Goes Ever On, which had some lovely calligraphy by the Professor and some intriguing glimpses of the First Age.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Road_Goes_Ever_On

We really treasured those tidbits.

Regarding the Authur Saha tenureship as editor of the year’s best fantasy: looking back through a fog of 30 or so years I would characterize the selection of stories as tending towards magic realism. But I admit my characterisation may be wrong. I might appreciate the selections more now but at the time I thought they were radically different than Lin’s (which I loved).

One of my favorite things about Lin’s DAW series besides the stories was his summation of the year in fantasy. He was so enthusiastic about what he liked. I still remember him promoting the novel The Birthgrave by a young Tanith Lee. (She will be missed also.)

I also particularly liked Carter’s review of Sword of Shannara (spoiler: he disapproved) in one of the Year’s Best volumes.

Also worth revisiting someday: His Flashing Swords series — all original, slightly longer sword & sorcery stories by a bunch of great authors including Michael Moorcock and C.J. Cherryh.

Re Joe H: I remember his review of the Sword of Shannara also. He basically said it was a plagiarism of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Coming from an author who imitated his idols closely I thought this was a case of the pot calling the kettle black.

I too remember Carter’s slam of Shannara. I got the feeling that what irked him most wasn’t the “homage” factor (as Charles says, LC didn’t have a leg to stand on in that regard) – it was the fact that a book that wasn’t much different from his own imitative productions somehow catapulted to the bestseller lists. As for those Carter novels, I shamefacedly admit to liking them. They’re decent fun as long as you understand what you’re getting – nothing original, but tributes to the masters done with more love than inspiration.

I think what really irked him (and he said as much in the review) wasn’t that Shannara was a pastiche of Tolkien — it was that it was pretty much a beat-by-beat copy of Lord of the Rings. Kind of the difference between reading Tower of the Elephant and going, “I want to write a story about a northern barbarian who gets in trouble when he visits civilized lands!” vs. “I want to write a story about a barbarian who gets hired to steal a wizard’s jewel that turns out to be the heart of a rhinoceros-headed monster.”

This was very much a formative book for me – it was my first exposure to Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith. ‘The Dragon Glass’ was another favourite. ‘The Way of Ecben’ I remember as a big black hole in the middle of the book which I always circumnavigated any time I re-read the anthology. I’d totally forgotten Branch Cabell wrote it (if I ever knew in the first place) and certainly wouldn’t have associated it with the author of ‘Figures of Earth’ etc. The two Dunsany stories also stick in my mind, but I’d already read ‘The King of Elfland’s Daughter’ so he was a known quantity.

The bibliography at the end of the book was mighty intriguing for this 14-year-old.

“The Maze of Maal Dweb” is something of a downer, and also very weird, but the Xiccarph stories, together with “The Demon of the Flower” (all of which are in the Carter-edited Xiccarph volume) are among my favorite CAS stories. I’ve noticed that his various imaginary milieus (Hyperborea, Zothique, modern California, Mars, etc.) are written in very distinct styles. It’s almost as though the milieus were born from the styles he wanted to experiment with, and not vice versa. In his planetary fantasies he strikes me as more of a jeweler than an architect, interested in creating beautiful patterns rather than in giving us a clear protagonist with a satisfying plot arc. I also like these stories because they really are planetary while remaining purely fantastic; it’s hard to think of other examples of that.

As an aside, I sometimes wonder why Carter chose Xiccarph as the name of the fourth volume, given that there were only two Xiccarph stories. Admittedly, they were great stories …

Major, I meant to comment on the bibliography, but it was late and slipped my mind. I was initially disappointed by it, but then I considered that in 1969 it would have been a pretty thorough bibliography of what would have reasonably available.

Raphael, I’ve not read Xiccarph but I will before I’m done. You’re right about “Maze” being a downer. I was a bit disappointed in the ending. I’ve got a complete set of the BAF series, but I don’t have reading copies of Xiccarph or Zothique. My introduction to the BAF series was Hyperborea. Your point about Smith using different styles is an interesting one. I’ll try to pay attention to the differences as I read through the books.

As several of you have pointed out, and quite well, it was Carter’s selections that really allowed readers to find works they’d been unaware of. And I don’t mean jsut the bibliography and the authors included in his anthologies. If there were other works by a particular author, Carter usually included a list of them either at the front of the book or in his introduction. I’m referring to novels here, btw. It’s easy to forget that the internet didn’t exist in those days, and as a consequence it was harder to establish communities of like-minded individuals who could make recommendations.

The bibliography was an extension of Carter’s comments at the beginning of the various selections. It was nice to have the bibliographic entries in one convenient place. Carter had two goals — the obvious “for further reading” one, and also to promote the new Ballantine Fantasy series. I don’t know how much of a financial risk the company took in reprinting old books by authors who were probably unknown to most readers.

He’d probably have figured that many of his readers would be pretty young — people who’d recently discovered Tolkien. He’d have been right, in my case. I’d turned 14 some weeks ago when this book appeared. Although I have largely outgrown Lovecraft, I retain the impression that The Young Magicians was the first place I’d encountered the term “Cthulhu Mythos.” It sounded like something vaguely Inca or Aztec to me; I seem to have had a very hazy sense that a “Cthulhu Mythos” story might be set in steep Andean-type mountains. Sort of a Rider Haggard scenario… perhaps by then I’d at least looked at Haggard’s She, which was another book for the existence and attractiveness of which I was indebted to Carter, thanks to a reference in his Look behind book on Tolkien. Carter did set me off on some library quests, probably intensifying an attraction to libraries that had already been well established.

In short, reading Carter wasn’t just a matter of enjoying fantasy; it was about getting the bug of Looking For Books. Even when one had perhaps outgrown a lot of the material that Carter presented, one retained that bug in one’s bloodstream, the condition exacerbated by the pleasure of discovery repeated over many years. I already liked prowling libraries when I read The Young Magicians, but this little paperback, as I said, intensified the condition.

Major, I think the Ballantines were reasonably safe in reprinting old books and knew it. They had already reprinted most of Eddison, the Gormenghast books, and Lindsay’s Voyage to Arcturus when they launched the BAF series and had also published two novels by Peter S. Beagle, The Last Unicorn and A Fine and Private Place. Beagle was a relative newcomer at the time. All of these would later be reprinted as part of the series.

They had had success, or at least not lost money, on these titles. It made sense to give Carter a chance to see what he could do with other old fantasy books. The King of Elfland’s Daughter, The Blue Star, and Lud-in-the-Mist were all reprinted with new covers after the BAF series was canceled, so some of the titles must have made a profit. There may have been others, but those are the ones I can think of off the top of my head.

Of course, Carter wasn’t content to just do reprints. He also published new works. Katherine Kurtz being the most prominent new author in the series.

I agree with you completely that Carter, in addition to promoting BAF titles, had an agenda with his recommendations. He wanted to build an audience who loved fantasy. In that I think he was successful.

I already had the bug of Looking for Books by the time I got to the BAF series. If there’s a vaccine for it, I don’t want it.

Most or all of the Cabell were also reprinted as Del Rey books with new covers; likewise the Evangeline Walton (or were those still Ballantine? but at least they did publish the fourth volume in her series). And the Lovecraft Kathath and Sarnath volumes, of course.

I kind of came to the BAF by accident in the 1980s & 1990s — found a couple of the Smith collections in a local used book store, then started seeing & picking up other used books with similar cover styles. Initially, the one Carter anthology I had was Golden Cities, Far, which I had some trouble actually getting into.

I wonder if Ballantine (or whoever owns Ballantine or Ballantine’s records — is there a Ballantine Books any more?) still has sales records for the BAF series. It would be interesting to know how many copies were printed and sold.

I imagine that most people who’ve read widely in the series would agree that it was a varied lot. It contains one of my absolute most favorite books — Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday — and others than I think very highly of indeed (such as MacDonald’s Lilith); and also some books that have stumped me, that I just didn’t get into. How many BAF fans have read The Blue Star, or Beyond the Golden Stair, or Khaled, etc.?

Joe H., I’d forgotten about the Cabell reprints. I actually read The Silver Stallion in that edition because it had Carter’s introduction with little to no changes. And I think you’re right about the Walton novels as well. I have at least one later reprint somewhere in the house. I’ve not read Golden Cities, Far yet but I intend to when we get to that point in the sequence.

Red Moon and Black Mountain was reprinted with a new cover before the BAF series ended, but I don’t know if it had an additional reprinting later.

Major, I would love to see the sales records for the BAF series. If they still exist, they’re probably in some corporate archive and considered proprietary information.

No argument that the selections were pretty varied. I think the main criteria Carter used was did he like it. He was an honest enough critic that he could acknowledge the flaws of many of the works he chose; just check some of the things he said in the introductions. So I think how well an individual liked a particular book would be a good first approximation to how closely that reader’s tastes matched Carter’s.

I’ve not read The Man Who Was Thursday but have heard good things about it. We’ve covered Lilith and The Blue Star in previous installments of these posts. I intend to read Beyond the Golden Stair and Khaled. At this point, the only titles I am not planning on reading (and I reserve the right to change my mind on this) are the remaining Cabell titles.

I just did a quick count, and so far we’ve looked at the first 12 (albeit slightly out of sequence) plus three later books. The next three in sequence are writers whose works we’ve looked at before (Dunsany, MacDonald, and Lovecraft). After that the frequency of repetition drops off as Carter began to include greater variety of authors.

I read The Blue Star, Major, and I differ from westkeith (if I remember his verdict rightly) in thinking very highly of it. That was one of the great things about the BAF – it was a smorgasbord, and if you didn’t like one dish, that was fine; there was sure to be another that would be just to your taste.

Again Lin Carter’s great legacy. He helped get Sword and Sorcery and most fantasy/science fiction back in popularity again and laid the foundations for it to be accepted by mainstream society. Sadly and I’ll say again it hurt him as a writer for he was a ‘good’ writer and thus appeared as a hack compared to all the greats he saved from total obscurity. Also he was semi homeless and died of cancer in the 80s or something.

To Major Wootton, I think Ballantine is just owned by another major label, probably TOR – Google’d it- Random House – Their own web lists it, they don’t even mention Lin Carter.

I collect Carter, both his fictions, those I’ve read I like – and especially his books about fantasy and collections. I saw the article on “Dragons, Elves and Heroes” but have you reviewed “Golden Cities, Far”? I did a quick search here (then a longer Google search of Black Gate) and didn’t find it and I browse this site pretty frequently. It’s a collection of old tales, mythology, stuff from The Arabian Nights, Mideval tales, etc. Essentially it’s a sample of what influenced Carter to like Heroic Fantasy so much, I remember him writing he was “Searching for what I called ‘Long Fairy Tales'”…

Thomas, as I’ve read more of the BAF series, I’ve thought about The Blue Star. And while I still think the “hero” was a bit of a drip, I’m not sure I would have quite the same opinion if I reread it. One thing I’ve come to realize by reading these titles is how generic fantasy has become.

Before you stone me, hang me, or turn me into a newt, let me elaborate. There’s still a wide variety of subgenres with authors doing some very interesting things, but the writing isn’t that different from one book to the next. I will freely admit that maybe I’m not reading the right books, but I just don’t see the stylistic range among contemporary writers that I’ve seen in the BAF series. Some of this is due to the periods in which the books were written. The series covers approximately a century, with excursions further back in time scattered here and there. There’s bound to be some differences in the writing.

GreenGestalt, I’ve been more or less covering the BAF series in order, with the occasional jump ahead. Golden Cities, Far is about a year out if I can average a book a month.

I did read through the entire series, and am (very, very slowly) going through a second time. Some of the books were slogs — for me, I think the worst was Shaving of Shagpat — some of the Morris was a struggle to get through, but I could at least appreciate what he was trying to do.

I don’t think the print runs were all that large; and I know there was an issue with Man Who Was Thursday in particular having a much shorter print run than the rest, that caused it to be the most expensive used BAF volume by far. (I want to say I paid maybe $50-$60 for my copy?)

The impact of Lin Carter on my bookshelves cannot be overstated — everything from Haggard and Merritt to the two University of Kentucky volumes of Amadis of Gaul.

Joe H., someone (and it may have you) said in the comments that The Shaving of Shagpat was a slog. I opened it at random just to see what the writing was like. Yikes. I’m dreading that one a bit now. After reading The Wood Beyond the World, I think I can handle Morris if I can catch the cadence of his prose and not rush through it.

I’ve only got one copy of The Man Who Was Thursday, but I don’t think I paid that much for it. Zothique is pretty expensive which is why I don’t have a reading copy of it or Xiccarph. And I’ve not hear of Amadis of Gaul. What’s that one about?

Yeah, that was probably me badmouthing Shagpat in an earlier thread as well.

Amadis of Gaul is a 13th Century Portuguese romance — there are a couple of excerpts in Golden Cities, Far.

I’ll bet quite a few BAF veterans were in their teens when they started reading the books, perhaps, as in my case, around the time the books first came out or in the few years thereafter. It may have done us no harm to have to have worked a bit at our reading. I remember making my way through The Shaving of Shagpat. Specifically I brought it along for slack time in a church youth group function or something like that. Nobody seems to have noticed!

The Man Who Was Thursday is simply one of the Great Books. There’s a superb paperback annotated edition (annotations by Martin Gardner!) from Ignatius Press that I can’t recommend too highly. And guys, you are really driving me to pluck that long-unread copy of Shagpat from my shelf. Contrarian that I am, if everyone hates it, I might just love it. (After all, I thought The Well at the World’s End and A Voyage to Arcturus were just great…really!)

Joe H., I haven’t attempted to collect the whole series. For one thing, Ursula Le Guin’s handling of one of the Katherine Kurtz books just killed it! I don’t mean that Le Guin was malicious; just utterly convincing. See her essay “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie.”

By the way, I wonder what kept Kenneth Morris’s Book of the Three Dragons from paperback reprinting so long, given le Guin’s championing of it. I believe it stayed out of print in any form till around 1982 when Hyperion reprinted it in a hardcover that cost me $25, a pretty hefty pricetag; it was paperbacked within the past 10 years or so. I borrowed a copy of the original American edition from one of my undergrad professors and read it around 1975…. It was published as a juvenile book, and maybe that put off publishers, but some of the things that were paperbacked as fantasy for (presumably) adult readers had been published as children’s books in hardcover, such as Ace’s editions of Garner’s Weirdstone of Brisingamen, The Moon of Gomrath, and Elidor…

We’ll be seeing a review of Red Moon and Black Mountain one of these days, I trust. Everyone should note that the BAF series offered this one with Bob Pepper cover art originally (which I like a lot) and someone else’s art in a later printing; didn’t like that design. There was also a book club edition with a Frazetta wrap-around painting that I don’t think is very good. When the time comes for Red Moon and Black Mountain, take a look at author Joy Chant’s little letter to the fanzine Mythlore of her book won an award. (I’ll have to look up the reference.)

I agree with your taste, Thomas Parker, as indicated in your 4:51 comment.

Morris is an interesting author for me, personally. I dutifully and with some enjoyment read him in the mid-1970s — in The Wood Beyond the World and The Well at the World’s End. Then just a few years ago I gave The Water of the Wondrous Isles a try — and found I liked it more than I’d expected I would. He remains of some interest where (I fear) I now find a lot of Dunsany to be unreadable, though he was one of my top five or so authors back then.

Yeah, I know the Le Guin essay has come up in at least one other thread on Black Gate; myself, much as I respect her as an author and critic, I find myself in violent disagreement with her attempt to define what does & does not constitute “real” fantasy.

(And there’s a case to be made that without Kurtz we wouldn’t have gotten George R.R. Martin or the other authors who are more into the grubby politics than the numinous.)

And I didn’t start out trying to collect the whole series. At first I didn’t realize it _was_ a series — I just happened to find a few volumes (Hyperborea, Poseidonis, Golden Cities, Far, maybe a couple of others?) in the used book store in my home town; then, when I moved to Minneapolis and started frequenting Uncle Hugo’s and Dreamhaven, I started recognizing other related covers on the shelves and adding those to the stack.

Eventually I got a checklist, of course, and in the end I got the final half dozen volumes or so from ABEBooks or Alibris or some such. (On the one hand, the internet has probably deprived me of much of the joy of the hunt; on the other hand, it’s made it infinitely easier to actually get the things I’m looking for.)

And I read the whole series initially because I had picked up James Stoddard’s High House/False House and wanted to be sure I wasn’t missing any of the references …

Amadis of Gaul:

http://www.amazon.com/Amadis-Gaul-Books-II-Languages-ebook/dp/B004D4YW44/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1437686227&sr=1-1&keywords=amadis+of+gaul&pebp=1437686230062&perid=1AC6X3GJ5APGCDQMEYP0

Back in the day, I found BAF titles showing up at one or other of the Oregon used book stores I haunted. It was fun to pick these things up for, I suppose 65c a copy or so. It wasn’t unusual for me to pass them up when I saw them for sale new!

Joe H., personally if I’m going to read grubby politics I’ll go for something real such as Tanenhaus’s book on Whitaker Cahmbers, Perlstein’s Nixonland, or Robert Caro’s The Power Broker. There are so many interesting tangents you can follow up on since these deal with real people, events, and places.

Here’s the reference for the letter from Joy Chant: Mythlore 3:1 (Whole No. 9) from 1973, pp. 23-24. She mentions that the creation of her imaginary world long predated reading Tolkien, and her influences were Mary Renault and Rosemary Sutcliffe. I know we’re getting ahead of things since RMBM is perhaps many months ahead, but I thought I’d mention these things so they’re there when folks are ready.

I discovered a lot of old fantasy (Morris, Haggard, Dunsany) through Dover reprints in the nineties, when I was a teenager. I first read The Wood Beyond the World in a facsimile of the original Kelmscott Press Edition. Anyone who thinks it’s a slog with modern typography should give *that* a try. Apart from the covers, which I love, BAF was a boon to me mainly for authors who weren’t in public domain yet but also not likely to be in libraries, like Clark Ashton Smith. Alas, an inexpensive copy of Zothique eludes me as well.

Geez, go take care of family matters for a few hours and look at all the great conversation I miss.

Joe H., thanks for the link. I’ll be sure to check it out.

Major, I was about 15 when I first discovered the BAF series. And yes, I intend to read Red Moon and Black Mounntain. It looks like I’m going to have to pick up the pace a bit.

Oh, and Excalibur also had a later reprinting from Ballantine after the BAF series was canceled.

Laubenthal’s Excalibur?

I have a ridiculous memory associated with that one. It may have been some other book, but it seems I had a layover on a Greyhound bus trip (about a half-day trip) to see a friend. During the wait for my bus to transfer into, I went to the little variety (?) store next door to the bus station and was looking at the books, and there was Excalibur (maybe — it’s a long time ago). Well, the bus came while I was there and left without me. So there I am stuck in Roseburg, Oregon… I called my friend, and his brother, who had a driver’s license, had to drive all that way to come and get me and drive us back to Coos Bay. It was about two hours each way…

Steve, if you ever see this, thanks again for the lift and for being a reasonably good sport about it…

Does anyone know the circumstances regarding why the BAF series was canceled? Too many complaints about feckless kids missing their buses while looking at the titles in stores? : )

Major, yes. That Excalibur. And that’s a great story.

I’m not sure why the BAF series was canceled, but I’ll do some digging and try to find out.

I expect it was poor sales and/or the shift from Ballantine to Del Rey. It’s kind of funny — Merlin’s Ring has the Galliardo cover and the Lin Carter introduction; and on the cover is a circle pretty much exactly the same size as the Unicorn Head circle, but it just says, “FIRST TIME IN PRINT”.

“In his planetary fantasies he strikes me as more of a jeweler than an architect, interested in creating beautiful patterns rather than in giving us a clear protagonist with a satisfying plot arc. I also like these stories because they really are planetary while remaining purely fantastic; it’s hard to think of other examples of that.”

These are two really good points, Raphael. I read all CAS’s stuff, or as much of it as I could get my hands on. I think you’re absolutely right: CAS is principally a stylist – but what a stylist! The opening sequence of this story is a classic in my opinion. That said, I recently I picked up one of his books after a long hiatus. The first few stories made me wonder why I hadn’t read him in so long, but then a pattern made itself apparent. CAS’s characters invariably come to sticky ends. I think CAS can be held only partially to blame for this element of repetitiveness. Raymond Chandler once outlined why pulp held such a personal appeal for him (I should add that he was trying to distinguish it from standard detective fiction, which relied on the big reveal at the end):

‘The technical basis of the Black Mask type of story on the other hand was that the scene outranked the plot, in the sense that a good plot was one which made good scenes.’

Personally I think this is a telling observation – telling inasmuch as it tells us something about Chandler’s skewed priorities as a writer (his plotting was pretty shambolic) but also about the priorities of pulp in general. Even Conan fans have admitted that if you read a dozen Conan stories in a row they can get repetitive, but of course they were published with at least a month’s hiatus between each story. A pulp author sold himself by his stylistic virtuosity rather than his intricate plotting.

Your point about how the CAS stories constitute a unique fusion of fantasy and SF is also very valid. The giant metal servitors which guard the causeway up to the sorcerer’s castle, the four moons of Xiccarph – these are all sf trappings in what would otherwise by a traditional fantasy fare, and are what establish CAS as a true original.

[…] N (Black Gate) The Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series: The Young Magicians edited by Lin Carter — “A number of people, myself included, have said that Lin Carter’s legacy will […]

“CAS’s characters invariably come to sticky ends.”

Very true, they generally do; and I must confess to taking a guilty pleasure in the varieties of stickiness in their various ends! But I can think of a number of stories where they don’t; and again, the *type* of sticky end seems largely determined by the milieu. I recently listened to all five Night Shade Press volumes of his collected stories on Audible (the only convenient way I could get them), and this really stood out to me. A couple types of story I didn’t mention before, but that are also very idiosyncratic, are his Averoigne stories and his Captain Volmar stories.

I like the Chandler quote; I think people often forget that Chandler and Hammett and people were like that were writing at the same time and in the same kinds of publications as REH and CAS and HPL, and that the stylistic choices and audiences had a large overlap.

Raphael, I really liked the Captain Volmar stories. And you make a great point about Chandler and Hammett writing for a pulp audience, at least until the became famous.

Smith is one of my favorite authors, the Zothique stories in particular. Having said that, at this point I find about one book of his stories the max I can consume in a single stretch these days. Otherwise it’s like trying to eat an entire pint of Ben & Jerry’s Phish Food or something — really good, but kind of overwhelming and you know you’ll regret it later.

Joe H., it’s been a while since I read much Smith, and that has mostly been isolated short stories. If I stick to the sequence after The Broken Sword, I should get to Zothique by the end of the year.

Does anyone know how the artist assignments for the BAF books were made? Did Ballantine have an art director who saw to this? Did Carter have any input?

When we talk about the BAF series, we generally talk about the textual content, although someone might mention liking the cover art for a given book. But what about the way the cover art and typography helped to make the series appealing?

What guidance were the artists given, if any, when they received an assignment?

The covers generally seemed fresh and successfully conveyed the impression of fantasy for grown-up readers. Part of that freshness may be attributed to the series -not- using the familiar artists for sf and fantasy such as Freas, Gaughan, Frazetta, Powers, Schoenherr, Emshwiller and so on, much as we might like some of the work of those artists.

I hope some discussion of this “aging” Blackgate entry is still possible.

The Young Magicians deserves special consideration because it is, in a sense, the real “launching” of the Ballantine Fantasy series. Yes, Ballantine had released a number of titles already. Most of those, however, didn’t have Carter introductions. And it was in -this- early offering in the series that Carter presented (or, in the case of Dunsany, Morris, and Cabell) re-presented authors who would be notable in the series during its five-year run. I suspect that, for a fair number of readers, The Young Magicians was their first purchase in the series — lured by the attractive cover and the prospect of new content by Tolkien.

In this book, more clearly than in any other so far in the series, Carter set out what -he- meant by (modern) adult fantasy. He demonstrated his credentials and he indicated where the series was going.

And by the end of the series, that “mission” had been accomplished. Really, what was left unreprinted by the time the BAF series ended?

One can think of odds and ends, to be sure, some of which would appear from Newcastle or other publishers; but most of the classic modern fantasy in the English language had been reprinted by Ballantine or, occasionally, other publishers around the same time. By the time Avon reprinted Rachel Maddux’s The Green Kingdom in 1977, what was left? A few years later Hyperion reprinted Kenneth Morris’s Book of the Three Dragons…

Major, you keep commenting, I’ll keep responding. I’m going to address your two most recent comments in one.

You make an excellent point and raise some interesting questions about the artists. At some point I’m going to do some posts about some of the artists who did BAF covers. That will probably take some research, so I’ve not gotten to it yet.

I don’t know enough about classic fantasy to answer your question in your second comment. Most of my knowledge of classic fantasy comes from the BAF series. Of course there were writers who occasionally dipped their toes in the waters of fantasy like Kipling and Dickens. Whether any of these authors had enough material for a book, or at least a book that would fit into the BAF line is not a question I have the knowledge to answer. Possibly some things from the pulps were still available. Carter selected a few things from the pulps here and there.

But Carter didn’t just try to publish reprints. He stated in the introduction to Deryni Rising, in the first sentence, that he and the Ballantines had hoped to publish new fantasy. And they did. The next two Deryni books, Hrolf Kraki’s saga, Double Phoenix, Excalibur, and Red Moon and Black Mountain were all original, and there may be others I’m not aware of.

So, yes, Carter did reprint most of the most important classic fantasy, but as far as publishing new works, I don’t think he was finished. I would like to have seen what other titles he would have found in the slush pile.