The Golden Age of Science Fiction: Manly Wade Wellman

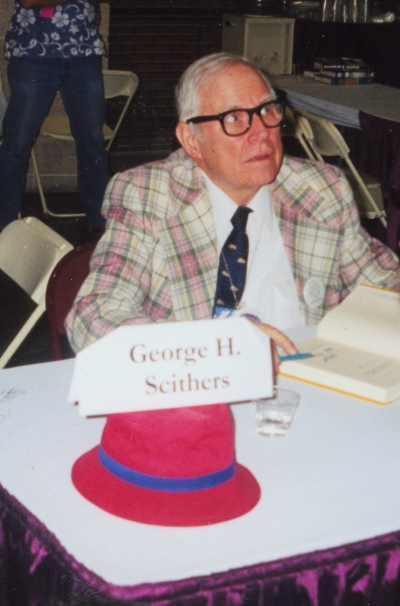

The World Fantasy Awards are presented during the World Fantasy Convention and are selected by a mix of nominations from members of the convention and a panel of judges. The awards were established in 1975 and presented at the 1st World Fantasy Convention in Providence, Rhode Island. Traditionally, the awards took the form of a bust of H.P. Lovecraft sculpted by Gahan Wilson, however in recent years the trophy became controversial in light of Lovecraft’s more problematic beliefs and has been replaced with a trophy of a tree with a full moon. The Lifetime Achievement Award has been part of the award since its founding, with the first one being presented to Robert Bloch. In 1980, the year Wellman was recognized, the convention was held in Baltimore, Maryland. Judges were Stephen R. Donaldson, Frank Belknap Long, andrew j. offutt, Ted White, and Susan Wood.

Manly Wade Wellman was born in Kamundongo in Portuguese West Africa (now part of Angola) on May 21, 1903, where his father was serving as a medical officer. When he was six years old, his family moved back to the United States and Wellman attended school in Washington, DC and prep school in Salt Lake City before going to Wichita Municipal University to earn a BA in English.