In August of the first year of the reign of Emperor Titus Flavius Caesar Vespasianus Augustus, the volcano Vesuvius erupted in the south of Italy and destroyed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Thousands of lives were lost. Out of the fire, ashes, and pyroclastic flows, an Italian film subgenre was born.

In August of the first year of the reign of Emperor Titus Flavius Caesar Vespasianus Augustus, the volcano Vesuvius erupted in the south of Italy and destroyed the cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Thousands of lives were lost. Out of the fire, ashes, and pyroclastic flows, an Italian film subgenre was born.

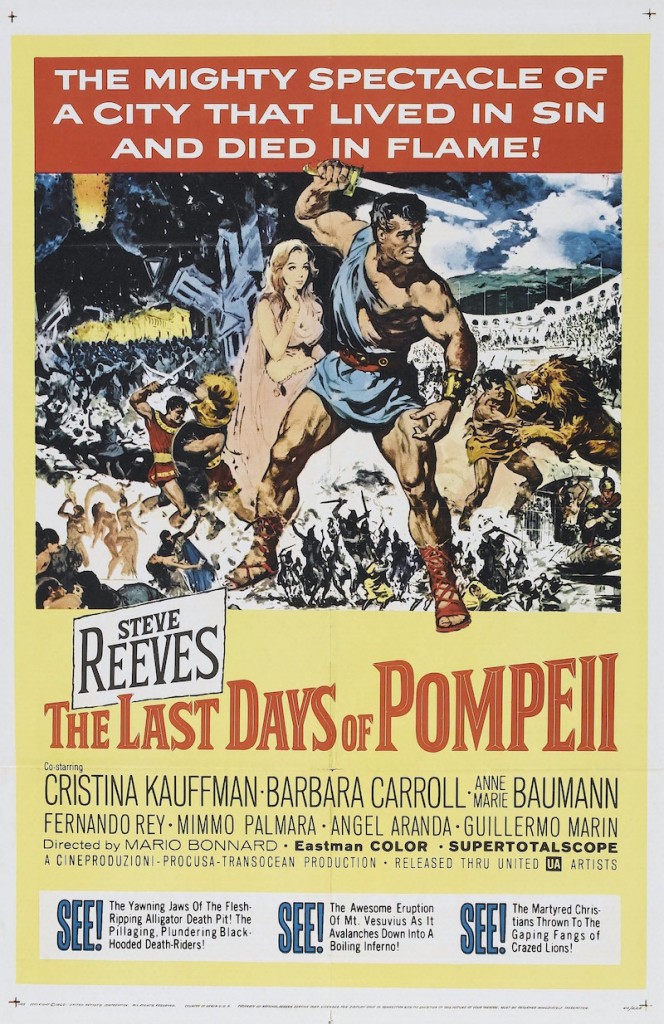

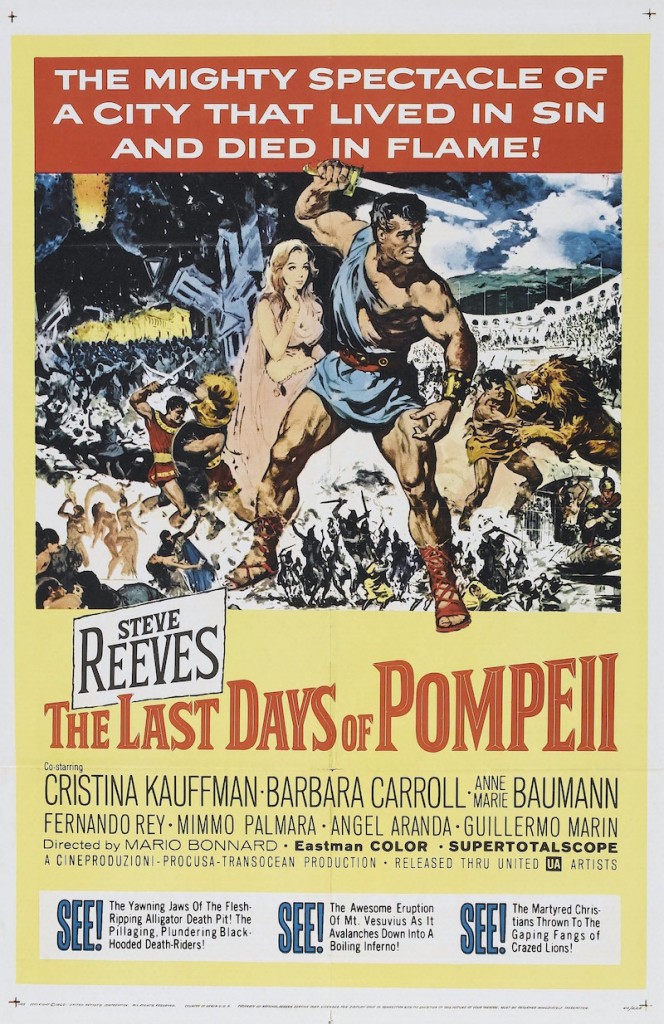

The 1959 film The Last Days of Pompeii (Gli ultimi giorni di Pompei) is the most famous of the many journeys Italian cinema has taken into the story of Vesuvius’s first-century eruption. Ostensibly based on Edward Bulwer-Lytton’s bestselling 1834 novel, the movie is a sword-and-sandal (peplum) riff that departs freely from its source so it can work as a vehicle for new megastar Steve “Hercules” Reeves. Reeves was at the height of his stardom and the peplum genre was also approaching the summit of its commercial success. There were loopier and cheesier days ahead for sword-and-sandal movies — I would argue more fun days — but for class and cash, The Last Days of Pompeii is a pinnacle. It lumbers sometimes under the weight of trying to appear like a serious prestige picture, but the lust for action entertainment carries it along. If you want to watch a dead serious epic from the same year, you have Ben-Hur. If you want to watch masses of polystyrene walls and pillars rain down on the cast and a hero slay lions and crocodiles, stay here.

Mario Bonnard is credited with directing The Last Days of Pompeii, but he fell sick on the first day of production. The man who took over the job was the assistant director, Sergio Leone. Yes, that Sergio Leone. Leone already had extensive experience working on Hollywood epics shot in Rome, including Quo Vadis. He proved he could helm a big feature with The Last Days of Pompeii, and soon after landed his first credited director job on another peplum, the fantastic romp The Colossus of Rhodes (1961), which I humbly submit is the pest peplum of all time. Two years later, Leone jump-started the genre that would surpass sword-and-sandal movies as the Next Big Thing in Italy with his Western, A Fistful of Dollars.

Although the eruption of Vesuvius is the reason the film was made, its story works as an ancient Roman drama even without the volcano. This isn’t a modern disaster film where the volcano is a constant subject of speculation with the actual on-screen disaster consuming the entire last third. Vesuvius appears in a few matte paintings and receives almost no mention again until the last ten minutes, when it interrupts the finale in the amphitheater to become the big curtain-closer. Forget the former plot, everybody run away!

…

Read More Read More