A Hidden Synagogue in Tangier

The interior of the Nahon Synagogue, with lamps donated by local families

Both of my readers have probably been wondering where I’ve been the past few weeks. I just got back from one of my semi-regular writing retreats in Tangier, Morocco. Besides getting heaps of writing done, every time I go to Tangier I always discover something new in this historic and complex city. This time I found a beautiful synagogue hidden at the end of a tiny alley.

Nahon Synagogue was built in 1878 by a wealthy banker from the nearby city of Tetouan in honor of his father Mose Nahon. Or this might have happened in 1868. The plaque on the front of the building says 1868, the caretaker and the synagogue’s literature say 1878.

The history of Jews in Tangier stretches back way before the 19th century. Archaeologists have dug up potsherds decorated with menorahs dating from Carthaginian times. Nothing else is known about Tangier’s Jewish community for this early period.

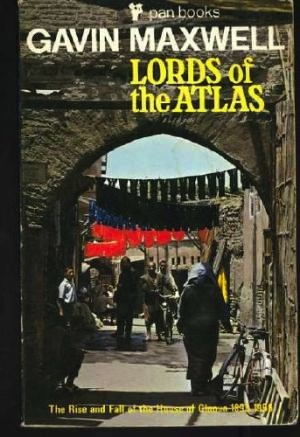

For people who have never been there, Morocco conjures up images of decadent ports, imposing casbahs, mysterious medinas, and mountains filled with bandits. It’s a mystique the tour companies like to perpetuate for this modern and rapidly changing country.

For people who have never been there, Morocco conjures up images of decadent ports, imposing casbahs, mysterious medinas, and mountains filled with bandits. It’s a mystique the tour companies like to perpetuate for this modern and rapidly changing country.