High Space Opera: Jim Starlin’s Metamorphosis Odyssey and Dreadstar

Recently, Black Gate overlord John O’Neill reported the news that Jim Starlin’s comic-book creation Dreadstar was in development as a TV series. Starlin will be a writer and executive producer of the new show, which is to be developed for television by Universal Cable Productions and Benderspink. No network was announced for the series, but io9 observed that Universal’s behind a number of shows for Syfy, where a Dreadstar show would presumably fit nicely.

Recently, Black Gate overlord John O’Neill reported the news that Jim Starlin’s comic-book creation Dreadstar was in development as a TV series. Starlin will be a writer and executive producer of the new show, which is to be developed for television by Universal Cable Productions and Benderspink. No network was announced for the series, but io9 observed that Universal’s behind a number of shows for Syfy, where a Dreadstar show would presumably fit nicely.

As it happens, I was a fan of Dreadstar when it was being published back in the late 80s. It had been years since I’d looked at an issue, though, so the news of the TV deal prompted me to dig out the old comics and go through them again. I ended up with mixed feelings. For me, at least, the golden age of Dreadstar was about twelve. But if I can see problems with the book more clearly now, I can also see what works. And I can see how an ongoing TV show makes a certain amount of sense.

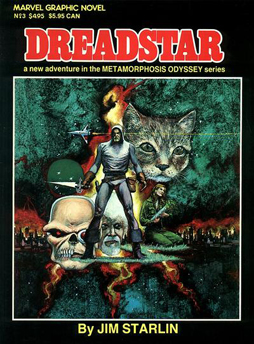

To explain that I need to start by going through the book’s publishing history. This gets complicated. Before Dreadstar there was The Metamorphosis Odyssey, a painted serial that ran for the first nine issues of Marvel’s Epic Illustrated. Epic was an anthology of creator-owned work somewhat along the lines of Heavy Metal magazine. By the time Starlin’s serial ended, late in 1981, he’d also published a related story through Eclipse Comics, a painted story called The Price. (Originally in black-and-white, it would later be reprinted by Marvel in colour. The Metamorphosis Odyssey, meanwhile, was in black-and-white for its first few chapters, then switched to colour as it went on.) The next chapter of the story came in Marvel’s third “graphic novel” — a line of books which somewhat resembled softcover European graphic albums — called, simply, Dreadstar.

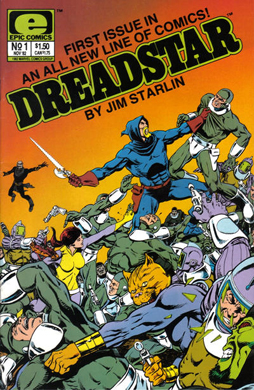

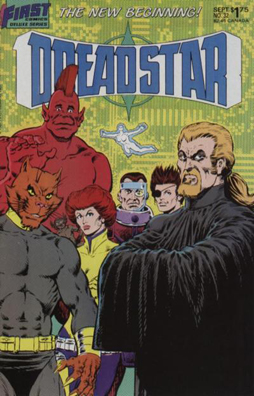

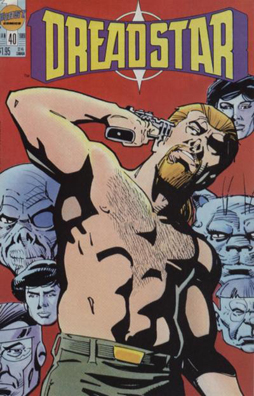

After another short story in Epic Illustrated, Starlin began an ongoing series published through Marvel’s new Epic line of comics. That lasted for 26 issues, at which point a financial dispute led Starlin to switch publishers (an unusual move at the time) and take the book to First Comics. Starlin had been writing and drawing the book himself up to that point, with the assistance of inkers, colourists, and guest artist Jim Sherman in issue 24; with issue 32 Starlin switched the tone of the book significantly, and with number 33 brought in a new artistic team of penciller Luke McDonnell and inker Val Mayerik. That lasted through issue 40, with Angel Medina providing pencils for issue 39. With issue 41 Medina took over as regular artist while Starlin handed the writing of the book off to Peter David. The title lasted through issue 64, at which point it was caught up in the linewide cancellation of First Comics. Plans to continue the title, and other First books, in a series of limited series came to nothing, though David did continue his story in a limited series in 1994 (that I have not read) with art by Ernie Colon.

After another short story in Epic Illustrated, Starlin began an ongoing series published through Marvel’s new Epic line of comics. That lasted for 26 issues, at which point a financial dispute led Starlin to switch publishers (an unusual move at the time) and take the book to First Comics. Starlin had been writing and drawing the book himself up to that point, with the assistance of inkers, colourists, and guest artist Jim Sherman in issue 24; with issue 32 Starlin switched the tone of the book significantly, and with number 33 brought in a new artistic team of penciller Luke McDonnell and inker Val Mayerik. That lasted through issue 40, with Angel Medina providing pencils for issue 39. With issue 41 Medina took over as regular artist while Starlin handed the writing of the book off to Peter David. The title lasted through issue 64, at which point it was caught up in the linewide cancellation of First Comics. Plans to continue the title, and other First books, in a series of limited series came to nothing, though David did continue his story in a limited series in 1994 (that I have not read) with art by Ernie Colon.

So that all sounds complicated. One thing worth pointing out from all the preceding, I think, is that Starlin was taking advantage of new creative options opening up in the comics field of the time. With the Metamorphosis Odyssey and Dreadstar, as well as the graphic novel, Starlin helped support Marvel’s experiments with creator-owned comics. He also tried out new colouring techniques in the ongoing book, just as he personally experimented with new media. It wasn’t the most ground-breaking comic of its times, but Starlin was trying new things and, crucially, maintaining control over his own creation.

At any rate, with all the publishing shifts came some plot changes; as the original serial promised, metamorphoses and an odyssey were both involved. That serial was set in a Milky Way galaxy in the process of being conquered by an evil species called the Zygoteans. The last survivor of their greatest enemies enacts a plan to stop them — by destroying the galaxy. Among the crew he gathers (or creates) to help him is a human from a planet called Byfrexia: Vanth, later to be known as Vanth Dreadstar, who possesses a mystical sword that gives him tremendous strength and the ability to absorb energy.

At any rate, with all the publishing shifts came some plot changes; as the original serial promised, metamorphoses and an odyssey were both involved. That serial was set in a Milky Way galaxy in the process of being conquered by an evil species called the Zygoteans. The last survivor of their greatest enemies enacts a plan to stop them — by destroying the galaxy. Among the crew he gathers (or creates) to help him is a human from a planet called Byfrexia: Vanth, later to be known as Vanth Dreadstar, who possesses a mystical sword that gives him tremendous strength and the ability to absorb energy.

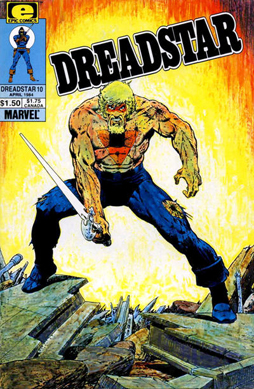

I find the story of the Odyssey a little slow; it only really seems to come to life when Vanth enters the scene. The art’s variable. Some of the painted chapters are wonderfully atmospheric, notably the second installment; others feel to me oddly static. One of Starlin’s greatest strengths as a comic artist is his dynamic sense of storytelling, and that doesn’t always come through in the highly-rendered paintings of the Odyssey. Plot-wise, Starlin introduces a number of characters who don’t end up doing anything distinctive, and so remain unmemorable. Vanth is the main exception, written and painted as violent, driven, and wrestling with his own doubts about violence and rightness. I don’t know when Starlin planned to centre the ongoing saga around him, but it was a good decision; he’s a character on a heroic scale, broad and yet with enough inner conflict to drive a series.

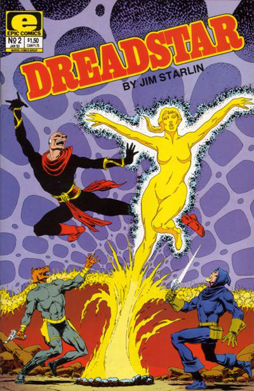

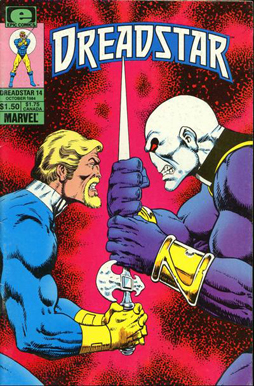

By the end of the Epic serial, the scene’s shifted to another galaxy. The Price introduces some of the key supporting characters in the series to come, as well as their home: the Empirical Galaxy. This galaxy, it turns out, is divided between two imperial powers. On the one hand are the forces of the kingdom called only the Monarchy, and on the other are the religious zealots of the Instrumentality, led by the brutal High Lord Papal. The Price follows the story of a bishop of the Instrumentality, a man named Syzygy Darklock, part of the Order of Vieltoor — religious wizards. Darklock’s brother is killed in the opening pages of the book, and his investigation leads him through some severe trials, along with foreshadowing of worse to come. At the end, horribly scarred, he leaves the church to seek out the next stage of his destiny, in the person of Vanth Dreadstar.

By the end of the Epic serial, the scene’s shifted to another galaxy. The Price introduces some of the key supporting characters in the series to come, as well as their home: the Empirical Galaxy. This galaxy, it turns out, is divided between two imperial powers. On the one hand are the forces of the kingdom called only the Monarchy, and on the other are the religious zealots of the Instrumentality, led by the brutal High Lord Papal. The Price follows the story of a bishop of the Instrumentality, a man named Syzygy Darklock, part of the Order of Vieltoor — religious wizards. Darklock’s brother is killed in the opening pages of the book, and his investigation leads him through some severe trials, along with foreshadowing of worse to come. At the end, horribly scarred, he leaves the church to seek out the next stage of his destiny, in the person of Vanth Dreadstar.

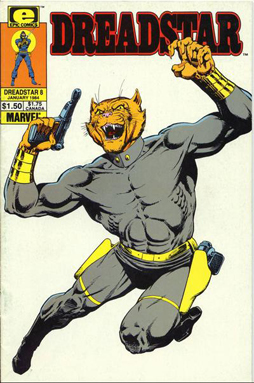

Who we find in the pages of the Dreadstar graphic novel. Vanth’s wound up on an out-of-the-way farming planet that’s home to a race of cat-people — genetically bred as a warrior race, the cat-people turned out to be pacifists with a knack for farming. Vanth finds a human woman among them, falls in love, and for years they live together happily. Then Syzygy Darklock shows up. You can see the disaster coming. Inevitably, tragedy strikes and the old warrior must take up his sword again and seek vengeance.

The art on the graphic novel and The Price seems more assured to me than the painting of The Metamorphosis Odyssey, faces more expressive and backgrounds more thoroughly designed. The plot of The Price is relatively inventive, but overly-baroque; by the end, when it’s clear who has been manipulting Syzygy and why, it’s hard not to think that simpler and better means could have been found for the same end. The graphic novel, on the other hand, suffers from a too-obvious structure. You know what’s going to happen all the way through. And yet the story never really creates a sense of tragedy because you know, also, that while bad things will happen the male lead will rise above them and use them as a spur to greater deeds. There is a minor twist at the end, in the form of Vanth’s specific actions and who he chooses as allies; but it’s not really enough to make the story distinctive.

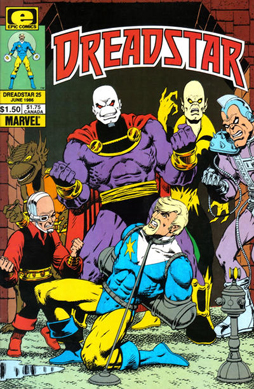

It does set up the ongoing series, in which Vanth Dreadstar, Syzygy, a surviving cat-man named Oedi, the blind telepath Willow, and a smuggler called Skeevo Phlatus form a band of rebels attacking the Instrumentality. Over the course of its run the series grew lighter in tone, developing a sprawling mix of super-heroics and high space opera. A complex plot threw out some loose ends but largely cohered, ending with a galactic war in the last Marvel issues and first First issues — after which the book changed tone again. In the wake of the resolution of the first major storyline, Vanth found himself in a bleak world hunting down criminals. The dark shift was emphasised by McDonnell’s jagged art. After Starlin left the book, David returned it to a more adventurous tone, aided by Medina’s detailed-yet-cartoony visuals (to this day I’m surprised Medina never emerged as an artistic superstar of the early Image Comics era); the plot was looser, humour more prominent and indeed excessive, and what thematic depth the book had maintained over its run was largely lost.

It does set up the ongoing series, in which Vanth Dreadstar, Syzygy, a surviving cat-man named Oedi, the blind telepath Willow, and a smuggler called Skeevo Phlatus form a band of rebels attacking the Instrumentality. Over the course of its run the series grew lighter in tone, developing a sprawling mix of super-heroics and high space opera. A complex plot threw out some loose ends but largely cohered, ending with a galactic war in the last Marvel issues and first First issues — after which the book changed tone again. In the wake of the resolution of the first major storyline, Vanth found himself in a bleak world hunting down criminals. The dark shift was emphasised by McDonnell’s jagged art. After Starlin left the book, David returned it to a more adventurous tone, aided by Medina’s detailed-yet-cartoony visuals (to this day I’m surprised Medina never emerged as an artistic superstar of the early Image Comics era); the plot was looser, humour more prominent and indeed excessive, and what thematic depth the book had maintained over its run was largely lost.

So let’s go back and look more closely at the run of the Dreadstar series proper (which is apparently the storyline the proposed TV show will adapt). Rereading it for the first time in years, I found some problems. Starlin’s dialogue wasn’t particularly distinctive, and his characters tended to sound alike. Some storytelling choices that seemed edgy or dark at the time now feel obvious if not distasteful — both Vanth and Syzygy have fridged women in their pasts, for example. The overall plot is sharply-executed, but some elements do remain underplayed, notably a false ‘saviour’ that Vanth promotes as an alternative to the gods of the Instrumentality. And the escalating power levels result in a number of bad tactical and strategic choices both by individual characters and by some of the empires (particularly when the ability to teleport comes into play).

You can also see where the story’s clearly speaking more to its own times than to ours. That’s often something especially visible in science fiction, and so here we have a galaxy that operates on a basically analogue and not digital conceptual framework. Which to some extent is an issue because of the story’s aspirations: Starlin comments on media and propaganda over the course of the tale, but obviously he focuses on television as the mass communications medium of the galaxy. As well, the idea of a galaxy divided between two super-powers is something that had more resonance during the Cold War. These things aren’t problems, in that every story ages; but that they stick out for me as much as they did suggests that I wasn’t entirely engaged with the story — and brings home how much the reading experience has changed. (As a contrast: I reread Starlin’s mid-70s run on Warlock not too long ago, and had no comparable experience.)

You can also see where the story’s clearly speaking more to its own times than to ours. That’s often something especially visible in science fiction, and so here we have a galaxy that operates on a basically analogue and not digital conceptual framework. Which to some extent is an issue because of the story’s aspirations: Starlin comments on media and propaganda over the course of the tale, but obviously he focuses on television as the mass communications medium of the galaxy. As well, the idea of a galaxy divided between two super-powers is something that had more resonance during the Cold War. These things aren’t problems, in that every story ages; but that they stick out for me as much as they did suggests that I wasn’t entirely engaged with the story — and brings home how much the reading experience has changed. (As a contrast: I reread Starlin’s mid-70s run on Warlock not too long ago, and had no comparable experience.)

Then again, there’s a level in which this actually helps the story, bringing out its pulp roots more clearly — it’s a slightly-outdated but still thrilling sf action story, like the stories that presumably inspired it. Comics storytelling has changed over time, as well, and so the storytelling style — the number of panels per page, the use of large blocks of text, and so forth — similarly reflects its era. Narration is often melodramatic. Exposition is obvious. In the Marvel issues, especially, several pages each issue have to be given over to recapitulating the story so far, slowing everything down. That said, Starlin was one of the great mainstream comics craftsmen of the 70s and 80s, and that incredible technique is on full display here. Most of the individual issues were, like a lot of super-hero books, structured around a fight scene or chase — and those set-pieces work stunningly well, as Starlin often discards dialogue entirely to move the eye from place to place across the page through compositional know-how. These scenes are incredibly well-paced, each with its own dramatic structure, its own rhythm of tension and release.

The visual storytelling is strong, then, if somewhat classical in tone. But unlike a lot of comics of the era the long-term plotting is detailed, and here is where it does feel a little like a contemporary TV show. Starlin told a single story over twenty-eight issues, and it’s possible now to imagine that adapted into a TV season — or into several seasons. The core plot ideas may have to be tweaked a bit, but the basic structure is clear.

The visual storytelling is strong, then, if somewhat classical in tone. But unlike a lot of comics of the era the long-term plotting is detailed, and here is where it does feel a little like a contemporary TV show. Starlin told a single story over twenty-eight issues, and it’s possible now to imagine that adapted into a TV season — or into several seasons. The core plot ideas may have to be tweaked a bit, but the basic structure is clear.

Which raises the big question: is it worth doing?

Anything can be made out of anything. But what strikes me as odd about Dreadstar is the way it seemed to grow more attenuated over time. To dwindle thematically. Granted that it kept changing throughout its run, it seemed to consistently evolve into more mainstream incarnations of itself — if only ‘mainstream’ by the standards of the comics field of the 1980s. By the time Starlin left the book, it felt at times like self-parody. That only grew worse when David took over, but long before that I came to think that Starlin had been growing less personally invested with the book. There seemed to be less and less metaphorical power in Dreadstar; plot came to overwhelm ideas.

Starlin, of course, made his name at Marvel in the 1970s writing and drawing Captain Marvel and then Warlock. His Death of Captain Marvel was Marvel’s first graphic novel (the Dreadstar graphic novel was the third in the same sequence). A few months ago I wrote in a post here that these stories were “psychedelic cosmic fables, Métal Hurlant done a la Marvel with a kind of Moorcockian emo irony.” That was in a review of Guardians of the Galaxy, many of whose characters were based on Starlin’s creations. (And with the success of that movie you can see why a TV show based on another of Starlin’s superhero space operas would be attractive.)

The point I want to make about these books is that, whether they were fully realised in terms of narrative craft or not, they were driven by a vaulting ambition. Thematically they were a heady brew, stories about death, religion, power, change, and inevitable doom, wrapped up with pseudo-Catholic imagery and a distrust of authority. There’s an excellent interview with Starlin at the Publisher’s Weekly web site in which Starlin remembers going to a Catholic school:

The point I want to make about these books is that, whether they were fully realised in terms of narrative craft or not, they were driven by a vaulting ambition. Thematically they were a heady brew, stories about death, religion, power, change, and inevitable doom, wrapped up with pseudo-Catholic imagery and a distrust of authority. There’s an excellent interview with Starlin at the Publisher’s Weekly web site in which Starlin remembers going to a Catholic school:

[T]he school nuns, who were the majority of the teachers at this particular parochial school, were right-wing, card-carrying John Birch Society members. By the time I was in third grade, I already knew that the class-conscious, and often racist, bile coming from these supposed teachers was utter nonsense. I remember one nun denouncing President John Kennedy for his stand on civil rights. She was certain that his “vile attacks” on the country’s class structure would bring about Armageddon. With a background like that, I couldn’t help but question the validity of all religions.

Later, after being given a choice between jail time and military service, Starlin was in the American Navy during the Vietnam war:

My time in the service made it clear to me that what we were being told in our newspapers and newscasts, back in the States, wasn’t half the story of what was really going on. I worked as a photographer in an intelligence outfit and we would get these rolls of aerial film in every so often, showing the results of bomb runs along the Ho Chi Min Trail; mile after mile of bomb craters with the occasional shattered village thrown into the mix. Half the time, you could have easily mistaken these shots for photos of the moon. Again, this kind of thing couldn’t help but surface in my work.

The fascination with death that emerges in his comics reaches a kind of apex with the Metamorphosis Odyssey serial. The entire Milky Way is destroyed. And then … where do you go? I’m not sure Starlin found an answer. Some of Dreadstar reads like a second go-round with material that matters to him: like Captain Mar-Vell, Vanth Dreadstar’s a blond soldier who tries to become better but is constantly drawn to conflict and war. Syzygy Darklock doesn’t just have a similar name to Adam Warlock, he also has a bleak destiny haunted by the shadow of his inevitable death. (And he has a costume similar to the costume Starlin would design for Warlock in The Infinity Gauntlet; but then the black-and-red outfit is also similar to that of Starlin’s DC character The Weird, so it may well be a personal preference.)

The fascination with death that emerges in his comics reaches a kind of apex with the Metamorphosis Odyssey serial. The entire Milky Way is destroyed. And then … where do you go? I’m not sure Starlin found an answer. Some of Dreadstar reads like a second go-round with material that matters to him: like Captain Mar-Vell, Vanth Dreadstar’s a blond soldier who tries to become better but is constantly drawn to conflict and war. Syzygy Darklock doesn’t just have a similar name to Adam Warlock, he also has a bleak destiny haunted by the shadow of his inevitable death. (And he has a costume similar to the costume Starlin would design for Warlock in The Infinity Gauntlet; but then the black-and-red outfit is also similar to that of Starlin’s DC character The Weird, so it may well be a personal preference.)

It’s not necessarily a bad thing for an artist to revisit the themes that drive them. But with Dreadstar it didn’t feel as though Starlin was adding much new symbolic weight. And what was already there seemed to fade. As the book developed and changed, it seemed to become more super-heroic, less individual, less distinct. Vanth’s powers changed, and he got a costume. The bad guys developed a team of super-powered agents to go up against his team. And so on.

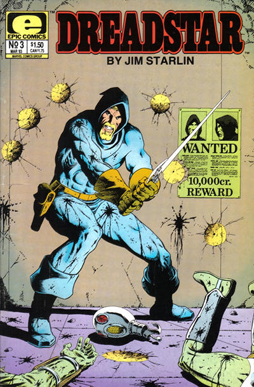

When Starlin turned the book over to McDonnell in late 1987, the storyline felt like a parody of the trends you could see on the average comics store rack. In the post-Watchmen and post-Dark Knight world, “grim’n’gritty” was the big thing. So Dreadstar was no longer a space opera; instead it was a strange mix of sf and hard-boiled noir. That might have been interesting, but it didn’t do either genre well. The social background of the setting was too underdeveloped to be believable, or even coherent, and the plots were too convoluted — again, you found yourself wondering why master manipulators were coming up with intricate plans and waiting for just this moment to activate them when there were simpler options available.

Normally the idea of a long-running book reinventing itself implies renovation. Dreadstar, unfortunately, did something else, becoming more generic as it went on. Then again, under Starlin it was never less than entertaining. Starlin’s clean, inventive art was always a pleasure, and the cynical undertones of the complex adventure story gave a bit of heft to the saga. Although occasionally slowed by exposition and bland dialogue, it’s still a fun book. With Dreadstar, as with other long-form serialised American comics, the creator got no second draft: as each issue was done, it was published. It’ll be interesting to see what happens if the TV show gets off the ground, and Starlin can revisit and revise his long-running odyssey.

Normally the idea of a long-running book reinventing itself implies renovation. Dreadstar, unfortunately, did something else, becoming more generic as it went on. Then again, under Starlin it was never less than entertaining. Starlin’s clean, inventive art was always a pleasure, and the cynical undertones of the complex adventure story gave a bit of heft to the saga. Although occasionally slowed by exposition and bland dialogue, it’s still a fun book. With Dreadstar, as with other long-form serialised American comics, the creator got no second draft: as each issue was done, it was published. It’ll be interesting to see what happens if the TV show gets off the ground, and Starlin can revisit and revise his long-running odyssey.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I think I read a bunch of the Dreadstar series that came from Epic; I was vaguely aware of the other incarnations (I was a hair too young for Epic Magazine proper when it came out).

And for some reason, reading the description of the story, I kind of keep flashing on Lexx, especially the first season or two.

> That was in a review of Guardians of the Galaxy, many of whose characters were based on Starlin’s creations.

> (And with the success of that movie you can see why a TV show based on another of Starlin’s superhero space

> operas would be attractive.)

Matthew,

Great article – and I think this sentence is particularly insightful. The big question I have for a Dreadstar series is “Why now?” Sure, Starlin’s getting a bit more attention these days as the creator of Thanos, but I couldn’t figure out why Dreadstar would suddenly become a hot property after three decades of being ignored (and now that it’s starting to seem a little out of date).

Focusing on Starlin’s AVENGERS connection was my mistake, The runaway success of GUARDIANS OF THE GALAXY was the piece I didn’t consider. If you’re a production house shopping around for a comparable property, why not spend your money on another comic created by the guy behind many of the GotG crew? Especially if it’s a similarly colorful space opera, packed with adventure, and plenty of opportunity for tongue-in-cheek humor?

I like the early Dreadstar stories, yeah. I agree that Starlin seemed less engaged as he went along, and I can’t help thinking that’s the whole reason he handed the book off to other people – he ended up looking at it as a “yeah, whatever” thing after a while and decided to move on to other things.

I don’t care for Peter David’s Dreadstar because I don’t like David’s work in general. His plots can get really tangled and his sense of humor is especially grating. If I thought he was funny I might not feel that way, but I don’t think he’s funny at all.

Starlin did a book with Malibu/Bravura (the same imprint that published the Dreadstar miniseries) in the 90s that I think was pretty good, a horror-adventure thing called Breed. Other than that, I think he’s rather fallen off as a storyteller. It makes me sad when he returns to Marvel and repeats Warlock vs. Thanos all over again.

Gawdz…

I always wanted a “Dreadstar” thing for a movie. Early on it was a “If I won the Giga Lottery and was going to donate it – and had already become rich or won a smaller lottery…” kind of I wish I could make it happen fantasy. But today it could be done rather easily with modern CG which I LOVE…

The only thing I’m on is just how the “Chew and Spew” machine wrecks everything. Dreadstar has a great STORY. That’s why something that was otherwise “Uh, superheroes in sci-fi star wars setting?” became so legendary.

Modern movie monopoly industries would just put up very good CG effects, chew the plot to crud and regurgitate it on the audience. No, really, they’d do a tip of the hat to 50s attempts at ‘immersive’ theater and have a ‘barf o tron” that’d spray chopped up bland porridge on the audience just to drive the point in…

[…] work that appeared in Epic and later under the First Comics brand (covered in a detailed review right here at Black Gate by Matthew David Surridge just last […]

[…] meant the coolest stories). Tragically, I had missed the Dreadstar stories in EPIC ILLUSTRATED (the Metamorphosis Odyssey), so when I started seeing comics with that same logo, I was intrigued. Especially with issue no. […]