Birthday Reviews: Janet Pack’s “A Coin for Charon”

Janet Pack was born on November 5, 1952.

Pack has collaborated with Kevin Stein on several poems and has co-edited anthologies with Margaret Weis, Robin Crew, and Martin H. Greenberg. She has occasionally published as Janet Deaver-Pack.

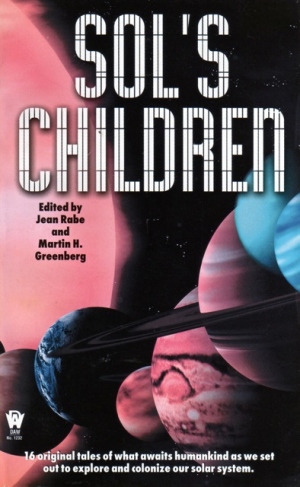

“A Coin for Charon” was published in Jean Rabe and Martin H. Greenberg’s anthology Sol’s Children in 2002. It has never been reprinted.

Pack’s story demonstrates one of the problems with writing about near future events, although in a slightly atypical way. Pack published the story, set on a space station in orbit around Pluto, in 2002 and in 2006, NASA launched the New Horizons mission to fly through the Plutonian system. When Pack wrote the story, little was known about Pluto and only one moon, Charon, had been discovered. By 2005, two additional moons had been found, Nix and Hydra. By the time New Horizons had reached Pluto and upended what we thought we knew about the planet, two additional moons, Kerberos and Styx, had been discovered. We have also learned that Pluto was not the frozen ball of rock and “methane-ethane-nitrogen-carbon-monoxide frost” that Pack described.

However, the focus of the story is less on Pluto and more on the dysfunctional relationship between two of the scientists on the space station, Velerie Heyer and Konrad Gregorius, whose relationship starts badly and only worsens as they get to know each other and are forced to work together, with the discovery of a magnetic element that Pack describes as forcing the tidal lock between Pluto and Charon, only cementing their enmity.

There are many historical stories about scientific relationships which go wrong and Pack takes the worst of all of those and transplants them to a remote space station with very tight living quarters, sure to exacerbate the problem. Although she mentions the rest of the station’s inhabitants, Heyer and Gregorius are really the only ones shown in any depth, although Heyer also interacts with Tobias Wellett. Without more input from the secondary characters, Heyer’s view of the situation is, of necessity, skewed and the reader is left wondering if the other characters have really kept to themselves as much as Heyer indicates rather than trying to alleviate the tension before the state of affairs could reach the point it does in the story.