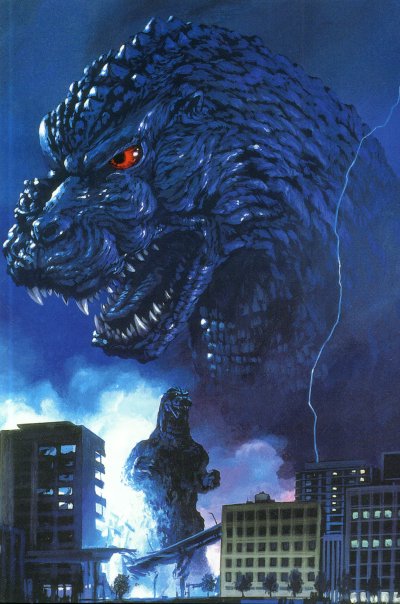

Godzilla, So-So Solo-Act: The Return of Godzilla (Godzilla 1985)

The most recent Japanese Godzilla film, 2016’s Shin Godzilla (aka Godzilla: Resurgence), is about to stomp into North America on Blu-ray. Shin Godzilla received an extremely limited one-week run in U.S. theaters in October 2016 — the theater where I watched it ran it once each on Saturday and Sunday morning — so this home video release is the first opportunity most people in Region A will have to see it. (I’ve reached a point where I no longer consider the world in terms of nations but of Blu-ray region coding. “What part of the world are you from?” “Region A.”)

The most recent Japanese Godzilla film, 2016’s Shin Godzilla (aka Godzilla: Resurgence), is about to stomp into North America on Blu-ray. Shin Godzilla received an extremely limited one-week run in U.S. theaters in October 2016 — the theater where I watched it ran it once each on Saturday and Sunday morning — so this home video release is the first opportunity most people in Region A will have to see it. (I’ve reached a point where I no longer consider the world in terms of nations but of Blu-ray region coding. “What part of the world are you from?” “Region A.”)

As prep for examining Shin Godzilla, I’m warping back to 1984 and the film in the series with which it has the most in common, i.e. the last time Godzilla went solo, with no other monster in sight: The Return of Godzilla. The home video timing works out well, since The Return of Godzilla only recently had its own digital video debut in North America on a Blu-ray from Kraken Releasing. In fact, the film hasn’t been available here on home video in any format since the late 1990s.

It’s also the first time the original version of the film has been legally available in the United States. When The Return of Godzilla first reached American theaters, it was as a grotesque Dr. Pepper-fueled mutant hybrid called Godzilla 1985. This Americanized version has been heavily slagged for decades for good reasons, but the original isn’t a hidden gem like the Japanese version of King Kong vs. Godzilla. Don’t expect a kaiju epiphany on your first viewing of The Return of Godzilla.

The Reboot of Godzilla

Known in Japan simply as Gojira, The Return of Godzilla was a reboot of the series long before that term for franchise reimagination became popular. It ignited the “Heisei” series of Godzilla films that lasted until 1996 and brought the legendary monster to a second height of fame and quality. Which is strange, since The Return of Godzilla doesn’t look as if it could ignite anything bigger than a tealight candle.