Birthday Reviews: David R. Bunch’s “The From-Far-Up-There-Missile Worry”

David R. Bunch was born on August 7, 1925 and died on May 29, 2000.

His second collection of short stories, Bunch! Was a Philip K. Dick Award nominee in 1994. Bunch also was the only author to have two stories included in Harlan Ellison’s anthology Dangerous Visions, which featured his stories “Incident in Moderan” and “The Escaping.” Many of Bunch’s stories are set in his world of Moderan

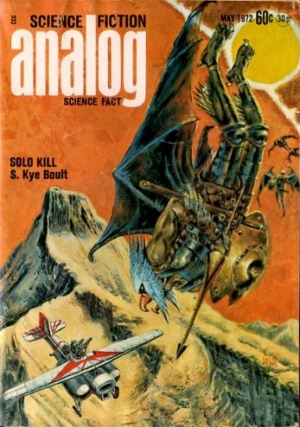

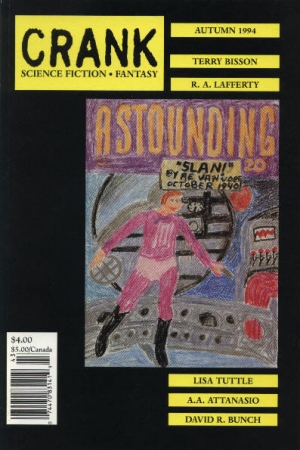

Bunch’s penultimate professional sale was “The From-Far-Up-There-Missile Worry,” which appeared in the fourth issue of Crank!, edited by Bryan Cholfin and published in 1994. As with most of Bunch’s work, this story has never been reprinted and is currently out of print.

“The From-Far-Up-There Missile Worry” is a strange stream-of-conscience tale clearly is set in a world in which some sort of annihilation is imminent, with the narrator living in dread of the end of his world and trying to come up with his reactions when the end, which he predicts will fall from the sky, comes. His fear is clearly demonstrated by his constantly shifting his thoughts from one area to another as well as his use of randomly capitalized words scattered throughout the story.

As the relatively short work progresses, Bunch builds more on the atmosphere of despair than providing any real indication of a story or even what is happening to the reader. The narrator’s internal dialogue about his concern for himself and his future is really the driving force, although by the end of the work, it becomes clear that humans, or partial humans, are in danger of being wiped out by the complete cyborgs that mankind created and which have gotten away from their control. Despite this, the story does not come across as anti-technological or a warning about mankind building its own replacements. “The From-Far-Up-There Missile Worry” is a study in an all-encompassing anxiety that cripples from the inability to take any meaningful action to either protect oneself or effect a change to the world.