Birthday Reviews: Jack London’s “A Thousand Deaths”

Jack London was born on January 12, 1876 and died on November 22, 1916. Best known as an adventure author for his novels The Call of the Wild, White Fang, and The Sea Wolf, he also wrote novels which would be considered proto-science fiction, perhaps most notably Before Adam. Active in socialist causes, many of his works supported the rights of workers, including his dystopian novel The Iron Heel, which has appeared as a preliminary nominee on the Prometheus Hall of Fame ballot twice.

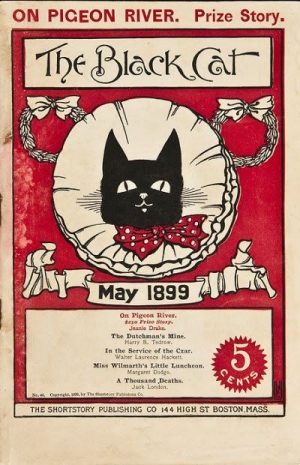

“A Thousand Deaths” was purchased by Herman Umbstaetter and published in the May 1899 issue of Black Cat. The magazine reprinted the story in 1917 and it has been published in several science fiction collections over the years, including a reprint in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1967 when Ed Ferman was the editor. It has been reprinted in various London collections and science fiction anthologies over the years.

“A Thousand Deaths” is the story of a man who has been disowned by his wealthy parents and forced to make his own way in the world. He has found a niche for himself as a merchant marine, but when the story opens, he is drowning in San Francisco Bay, having decided rather precipitously to leave the ship he had been working on. He passes out in the water and when he awakens, he finds himself revived on a pleasure yacht which happens to belong to his father, who does not recognize him.

His father is interested in finding a way to stave off death and has, in fact, brought the narrator back to life. Without revealing his identity to his father, the two agree that the narrator will allow his father to kill him in various ways and bring him back to life to test his various hypotheses. The father is depicted as a monster, reminiscent of Jules Verne’s Captain Nemo or H.G. Wells’s Doctor Moreau. His two assistants, whose only notable characteristic is that they are black, unfortunately, allow the casual racism of the period in which the story was written to shine through.

The narrator eventually tires of the experimentation, especially when he realizes that his father is doing much more to him than his father has told him. He effects an escape after managing an unlikely scientific breakthrough that allows him to follow in his father’s monstrous footsteps.

The story was clearly written at a time when it was believed that science would eventually be able to solve all of life’s (and death’s) problems, and while it doesn’t have a Frankensteinian “There-were-things-man-was-not-meant-to-know” lesson to it, London definitely makes the implication that technological advances needed to be tempered by man’s humanity.