Special Fiction Feature: “The Poison Well”

By Judith Berman

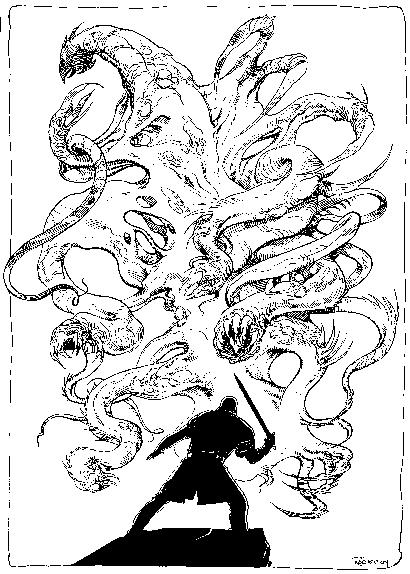

Illustrated by Denis Rodier

This is a Special Presentation of a complete work of fiction which originally appeared in Black Gate 7. It appears with the permission of Judith Berman and New Epoch Press, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. All rights reserved. Copyright 2004 by New Epoch Press.

Manvayar waited impatiently while Seppan’s mare plodded up the rise. At last Seppan reached the crossroads, and together they gazed down the lane that wound away from the high road.

Manvayar waited impatiently while Seppan’s mare plodded up the rise. At last Seppan reached the crossroads, and together they gazed down the lane that wound away from the high road.

“This must be the way,” Seppan said.

“They could have sent a guide for us,” said Manvayar.

Seppan smiled faintly. “You will get used to serving the Temple Court. No one wants to travel with an inquisitor on the hunt.”

Manvayar urged Raven down the bank of the high road and onto the lane, into the green shadows of the forest. He noticed that the country folk had done some cutting and coppicing along the edge of the lane, but further in the wood was an impenetrable tangle. The lord of this place had not even fired the brush for hunting.

Then he saw mounds of rock and a gap-toothed section of wall. The stones where the wall remained standing had been mortised together so closely that no weed had taken root.

“What is it?” Seppan asked, stopping his horse beside Raven.

“A Nariyo ruin,” said Manvayar. A trace of a path led toward the broken wall. He guided Raven down it a few steps.

Beyond the wall he could see an opening in the forest canopy. An old lattice of power prickled at his bones. He opened his soul-doors with care. And tasted something, power recently astir —

“Our business is at the manor,” Seppan said.

Manvayar glanced back. Seppan’s impassive face and priestly soul-mask concealed all trace of emotion, but from their brief acquaintance, Manvayar guessed the fat old inquisitor was yearning for his dinner.

He turned to the ruins and sent soul-touch questing a moment longer. Then, unexpectedly, the taste of putrefying flesh flooded his mouth. He gagged and nearly vomited. Old terror surged through his limbs. Raven reared up in response, whinnying shrilly. Manvayar slammed shut his soul-doors and clamped his will upon the sudden chaos of his emotions. “Here!” he shouted to Seppan. “It’s here!”

“What?” said Seppan. “Where?”

But it was already gone. With an effort Manvayar swallowed his nausea and moved his hand, which had seized his sword hilt, to stroke Raven’s velvet neck. He looked up. A breeze riffled the numberless leaves of the forest.

He understood why the inquisitors in the High Temple had sent him to this remote province. They would help cover his tracks, hide him from his old master. But in two scant weeks in the provincial capital, he had begun to feel impossibly lost. He did not belong in the placid countryside any more than a corpse-wagon belonged at a young ladies’ dancing party. The slow ride into these hills, while cloud-shadow and sunlight chased each other across the summer fields and he held Raven tightly in check to pace Seppan’s swaybacked mare, had not changed his mind. He had been sure the murder would prove nothing worse than a drunken quarrel and a bad dream sent by a country witch to plague her neighbors. The neighbors would fill the inquisitor’s ears with gossip while children chased puppies in the yard.

He had been wrong.

He was in familiar country again. The terrified guardsmen had not mistaken the power that had savaged their captain.

The necromancer was real.

The lane bore them steadily up the valley and into hedged fields of barley and amaranth. Soon scattered huts came into view. A peasant woman stepped back in alarm when she saw Seppan’s black robe and shaven head, the golden ear-spools and the death’s-head pendant bouncing on his chest. Then her eyes fixed upon Manvayar. Perhaps, he thought, she wondered why the Skull Priest’s man-at-arms did not wear Temple livery.

The peasant huts grew larger, exchanged thatch roofs for slate, coagulated into a village. As he and Seppan entered the market square, heads turned toward them, and silence seized peasants and tradesmen alike. The loudest sound as they rode through was the clang of iron-shod hooves on paving stones.

More green pastures; then the lord’s lead-roofed manor appeared atop a rise. The gate into the yard was wooden and new, but the wall surrounding the yard, and the manor itself, were built of ancient mortised granite.

Manvayar had ridden from the forest sunk half in trance, his soul-doors open and soul-touch reluctantly extended, and felt only the unease in the silent townsmen. Now, as they rode into the manor yard, and guards clustered around them, he closed soul-doors tight to shield himself from the distasteful smells of their unclothed souls.

The guards bowed to Seppan and helped him alight. Then they looked askance at Manvayar . A man-at-arms should have dismounted before his master.

“I’ll tend to my horse myself,” he said to them. “He’ll take the hand off anyone else who touches him.”

And the guards, eyeing Raven’s powerful build, the nervous blowing of his nostrils, did not argue.

Manvayar followed the guards to the stables, dismounted and tied his stallion to a rail. He had just pulled off saddle and pad when a young man in fine hunting leathers rode into the yard. The newcomer stopped near Manvayar.

Raven stretched his neck to snap at the other’s gelding. “Stay!” Manvayar ordered.

Raven pulled back, tossing his head. “That,” said the newcomer, “is not a lackey’s mount.”

“No,” said Manvayar.

The other leapt down and swaggered toward him on spurred and booted feet. The young nobleman was Manvayar’s age, but more powerfully built, and — a surprise — just as tall. He was also unusually handsome, with strong bones, dark eyes, and wavy golden hair pulled back with a leather tie. He came so close that Manvayar could smell his sweat.

“Who are you?” he asked, staring into Manvayar’s eyes. “Why are you here?”

Manvayar had never known how to respond to men whose every word and movement was a challenge. Sword-work he understood, exquisitely, viscerally. Once scholastic debate with priests and mages had delighted him. But games of domination ignited in him a tightly repressed fury.

He bowed. “I am Manvayar Duryen,” he said. “I came with the Skull Priest. I work for the Temple of Judgment.”

“In-deed!” The young nobleman took another step toward Manvayar. The smell of his body grew stronger. “And are you also a left-handed boy?”

Startled, for a second Manvayar wondered how the other could perceive it. He held Raven’s bridle with his right hand.

“A child of sorrow?” the lordling sneered. “A mage? A seer?”

Of course. Manvayar had heard the superstition often enough from ignorant folk on his father’s estates, and from the malicious at court: that a talent for magic was, like left-handedness or the inclination for sodomy, a curse borne of incest, perversion. That each necessarily accompanied the other.

“The Skull Priest finds me useful,” he said. And he turned back to Raven.

Even with soul-doors shut, he could feel the other’s gaze burning on his back. Manvayar made himself undo Raven’s neck-strap with his right hand. Finally the lordling turned and stalked toward the manor.

The room was large, with four arched windows and a carved wooden bed. They had been given one of the manor’s best — anything less would have been an insult to the Temple of Judgment. Still, the air was close and musty. Manvayar worked to open the casements and let in the evening breeze, but years of rust defeated him. The handles were going to break before they budged.

“Are you ready?” Seppan said. “Have you finished your washing?” Seppan seemed to think he bathed too often.

“Ready,” said Manvayar.

The lord’s family had already gathered in the hall. Most resembled the young nobleman Manvayar had encountered in the stable yard: tall, strong-boned and handsome. Lord Agard himself was stooped and gray-haired, his face lined, his teeth brown and already disappearing. He nodded first to a gray-bearded man who stood on his left — “My brother, Adoon” — and then to a short, dumpy woman with fewer teeth than he. “My wife,” he said. “You terrify her.” His contempt was obvious.

There was also the brother’s wife; the lord’s two gangling sons, neither of them the young man Manvayar had already met; the household Sun Priest; and finally the lord’s daughter. She stood in back, eyes downcast. Lord Agard did not seem to want to introduce her, and he shot Manvayar a hostile glance. Finally he ground out her name, “Aleid,” and then said, to Seppan, harshly, “You may speak to them all tomorrow.”

They moved to the table, the men to its head, women to the foot. Manvayar took a place below Seppan, who sat at the lord’s right hand.

At that moment the young nobleman he had met earlier strode into the hall. The other had changed his hunting clothes for a velvet robe and cap like his father’s, but he wore the robe open to show his fine pleated shirt and close-fitting hose. When he saw Manvayar, his eyes narrowed and his brows drew down.

“Avan,” Lord Agard said, gesturing. “My oldest son.”

“Why,” said Avan to Seppan, “do you require your lackey with you at dinner?”

Seppan glanced at Manvayar. “He is well-enough born.”

“If he isn’t a Temple lackey, what is he?” said Avan.

Seppan sighed. “The High Temple sent him to us,” he said. “He is… like myself, an investigator.”

An uncomfortable silence persisted through the fruit course and well into the soup. Manvayar made sure he used his right hand, and he kept soul-doors as tight as he could close them. But he could not shut out the acrid stink of their hostility toward him.

He had little appetite, anyway. The hall windows were shuttered despite the fine evening, and the airless room oppressed him. He found his eyes straying to the lord’s daughter. Something about her made him uneasy. Perhaps it was because he had hardly seen women of any sort in the years with his old master at Mount Massaren. And this girl was beautiful: dark eyes, fine strong bones, honey-dark hair streaked with gold. She wore a green dress over a white linen chemise, and her bodice pushed up her full breasts so that the pale swell of them just emerged from her clothing. She could not have been older than seventeen.

She reminded Manvayar of Raven. Perhaps it was the tense curve of her neck, fine tendons under velvet-soft skin, or perhaps it was the restlessness of her hands as they fidgeted with spoon and bowl. She did not speak or smile, or once look up. He noticed that, beneath the sleeves of her dress, her wrists were bandaged.

As the servants cleared soup bowls, Seppan spoke into the silence. “They are witnesses?” His gesture took in the whole family.

“No!” said Lord Agard, frowning. “No one here has seen anything. What happened has nothing to do with this house!”

“You said I should speak with them tomorrow,” said Seppan.

“I said you may speak with them if you must! I will not have anyone say I tried to shield my family from an inquisition.”

Seppan said, “The Temple report states the necromancer’s creature appeared in your stable yard. No one in your house witnessed it?”

“The thing followed the prince’s guardsmen to the manor,” said Lord Agard. “The prince has all sorts in his entourage, debauched courtiers, heretic priests — whores and sodomites everywhere you look.”

Seppan raised an eyebrow at this description of the Red Prince’s followers. “His entourage was not here. Only a cavalier with an escort of guards, come to deliver an invitation to the Ascension.”

“The cavalier was the prince’s man,” said Agard. “His fate followed him from some other place. If the necromancer was ever here in the flesh, he is long gone now.”

“But the necromancer killed Lord Tach two weeks ago!”

Agard frowned fiercely. The youngest boy, who had blurted the words, shrank back in his seat. “My son is mistaken,” said Agard. “Lord Tach could not have died by the necromancer’s hand. The necromancer was already gone.”

But Seppan just asked, mildly, “Lord Tach? Who was he?”

“A neighbor,” Agard said, “who thought himself good enough for my daughter.”

Manvayar, watching Aleid, saw her flinch.

Seppan held up his empty wine cup for the serving man. “And where,” he said, still in the same mild tone, “did this neighbor meet his unfortunate end? Was it also in your stable yard? I suppose there were also no witnesses?”

The lord flushed. “Are you mocking me?”

“I am merely asking the questions.”

“My father is right,” said the lord’s eldest son, speaking for the first time since challenging Manvayar’s right to sit at the table. “If the necromancer came from our lands, if he intended to stay, he wouldn’t call so much attention to himself here!”

“It’s sometimes difficult to judge the sense of a necromancer’s actions,” Seppan said. “An ordinary mage has to consume his own substance to work his spells. A necromancer can use as many souls as he can kill and bind. But it requires great strength of mind to consume the soul of another. The necromancer who is a priest or mage,” (here he glanced sideways at Manvayar) “who has already mastered the disciplines of mind and spirit, this man can dominate his captured souls completely and hide his crimes from even the most discerning. But often the necromancer is a dabbler, a weakling. He cannot achieve complete control. His ghosts drive him to madness. So the creatures appearing in your stable yard could be involuntary manifestations — outbursts of the necromancer’s fear or anger, one might say — that appear even when he would prefer to remain hidden.”

The servants began to lay out the meat course. Manvayar supposed that what Seppan said might be true. This necromancer was clearly not as skilled as his old master, from whom he had never tasted the faintest trace of forbidden magic until the end. And the swift brutality of the first death here, at least, did suggest a lack of control. A great necromancer, as he had discovered his master to be, did not kill his victims at first — perhaps did not even draw their blood. He would instead torment them as long as flesh could endure. It was not death itself that gave the necromancer his power, but the anguished emanations of the human heart.

Lord Agard’s voice cut through his thoughts. “So you like my daughter, lackey?”

Manvayar realized his eyes had found Aleid again, though she was not at all like the peasant girl he had discovered in his master’s binding-rooms. He turned to the head of the table. The lord glowered over a cup of wine; the gray-bearded younger brother’s gaze also fixed on him, full of hostility. Lord Agard’s splendid oldest son lounged in his seat, poking at his teeth with a golden toothpick.

Manvayar pushed away his plate. “My lord,” he said with enormous courtesy, “I notice that your house is very old, and must date to the time of our predecessors in this land. It’s unusual to see a Nariyo building so intact. Did your ancestors find the manor abandoned when they took possession of the valley, or did any of the old race still dwell here?”

The men still glowered at him. “Nariyo!” Lord Agard exclaimed, blinking with astonishment. After a moment he said, “There were a few necromancers here — so my grandfather told me. My ancestors dealt with them! They didn’t need an inquisitor to ferret them out.”

“And how long ago was that?” Manvayar asked.

“In my grandfather’s time,” said Agard. “All they needed were sharp steel and the Sun Priests’ holy prayers.”

“I saw a Nariyo ruin at the entrance to the valley,” Manvayar said. “Were Nariyo living there when your ancestors arrived?”

Scarlet, Lord Agard slammed down his wine cup. His brother looked away. The son still lounged in his chair, picking at his teeth, staring at Manvayar.

No one spoke for several moments. Finally the rabbity Sun Priest, who had kept silent the entire dinner, leaned forward. “It’s an unholy place,” he said with great intensity. “There is powerful poison in the well there. In a drought cattle sometimes find their way to it and drink. The poison torments them before it kills them. Horrible torments! They die in agony!”

A well of poisoned water? “Is a draft of the water always fatal?” Manvayar asked.

“Always,” said Avan, the lord’s son. “But we give a merciful death to any creature that drinks it.”

“I’m sure,” said Seppan, holding up his plate so the serving man could refill it, “that is very wise.”

After dinner, Manvayar called for more water to be sent to their room so he could wash away the smell of the rich food. As he dried his face, he noticed Seppan eyeing him.

“I would like to ask a favor,” said Seppan.

Manvayar put down the towel. “I am your servant.”

“Could you refrain from stirring up the family? I would particularly like to request that you keep your eyes — and your hands, should the occasion arise — off that girl. I trust you have learned that much self-control.”

“I’m sorry,” Manvayar said. He should indeed have exercised more discipline. “I didn’t intend to call attention to myself. It’s just that the girl — ”

“Leave the girl alone,” said Seppan.

“It’s just that there’s something about her — ”

“She’s pretty?” said Seppan. “You’d like to get under her skirts?”

Manvayar felt his face burn. He had no stomach for trying to explain. “It’s just that I don’t understand their reaction. They were angry with me on sight.”

“You don’t understand?” Seppan said. “A handsome young man, with a sword and a fancy horse, reeking of court polish, but dressed like a lackey? Everything about you shouts, ‘I’m a mystery!’ They don’t know what the inquisitor’s arrival will mean, but they know what kind of threat you are. Stay away from the girl, and try not to provoke her brother or her father again.”

Manvayar’s embarrassment deepened at this description of him. “I’m not trying to be mysterious. My father washed his hands of me years ago and I don’t own any other clothes. Even so, I can’t have been the first man to stare at the girl, and I haven’t done anything else to provoke them.”

Seppan sighed. “I take that back about your polish. Do you know anything about men or women? You don’t have to look at her. All they have to know is that she is going to look at you.

“Listen, please.” Now Seppan was completely serious. “I know you are a brilliant young mage, and feel wise in the ways of necromancy, and I am a fat old man without much talent. But if you are indeed here to serve the Temple, please don’t poke your fingers into every sore spot the family has. This girl is undoubtedly a very sore spot. You are a seer, aren’t you? Watch, listen, use your talent! Find these wounds before you open them again. Use them as a window into their hearts.”

In his old master’s eyes Manvayar knew this provincial inquisitor would seem inconsequential, even laughable. But he deserved Seppan’s reproach, and he had repudiated his master’s ways from beginning to end. If that meant trying to learn from a man with less talent than he, so be it.

Manvayar was willing to do as Seppan said, willing to try. It was just that he could hardly bear to use his talent this way. To open his soul-doors and, with his inmost self, touch those who could not mask their own emotions was like walking naked into a crowd of hostile strangers. The sour stink of lies, the crushing weight of contempt, the hot edge of anger fell on his unprotected soul like blows. Such a sensitive boy. He was ashamed of the fact. He valued mastery of the will above all human virtues. He ought to be able to wield magic as dispassionately as a sword. But he could not.

“So,” Manvayar said carefully, “you think we will find the necromancer within the household?”

“I think nothing yet, and meanwhile observe, and I recommend the same to you. Do you understand what I’m saying?”

“Stay away from the girl.”

Seppan sighed, rubbing his eyes. “Yes,” he said, “that, too.”

Manvayar slept that night on a pallet beneath one of the windows. Toward dawn he dreamed of footsteps in the hall. The footsteps became his own. They echoed as he passed through his master’s binding-rooms, searching. The dead lay upon stone blocks, wrapped with tarnished silver chains, or, half-flayed, they loomed above him like huge motionless birds. They cast wild shadows as his lantern guttered.

He opened his eyes and saw his old master staring through the window, face rippled by glass. Then he jerked fully awake and opened his eyes for real. There was no one at the window. An old moon leaned toward the brightening horizon.

The house was silent, dark, and airless as a tomb. Seppan did not stir as Manvayar dressed and left the room. The cooks had already begun to bustle in the kitchen. He saddled Raven in the stall by feel, and soon the two of them were cantering away from the manor.

He rode Raven among the green fields without paying much attention where. Chilly morning air poured over them like clean water. Slowly the dawn brightened. The lane entered an overgrown wood and at length curved around an oddly shaped boulder. Manvayar reined Raven to a walk, then a halt.

The top half of the boulder had been carved into a miniature maze, or a model of a city, or perhaps it was a tiny, mountainous landscape. He had seen these before, but never in such perfect condition.

The morning had seduced him and his soul-doors stood open to the world. Now, as clearly as if his eyes beheld it, he saw a figure approach from behind. A crude soul-mask made the figure as featureless as a block of wood. The hair on his scalp prickled.

“It’s the map of heaven,” said a voice, with vowels so thick he could barely understand them.

He turned in the saddle. Eyeing him frankly, a gray-haired peasant woman stood at the edge of the lane where a faint track led deeper into the wood. “You know what that means,” she said. “You’re a child of sorrow.”

Manvayar recognized her then. She was the woman they had passed in her garden yesterday, who had stared at him long and hard. Her stare now felt like insects crawling on his scalp. She was a witch, if obviously an unlearned and unsubtle one.

“Where is the temple this belongs to?” he asked.

“Temple?” she said. “This belongs to no temple, sir. The gods put it here. We children of sorrow, you and me, we don’t need the priests to talk to heaven.”

Manvayar stifled the urge to tell her, sharply, that he, an aristocrat’s son and scholar, had nothing in common with a peasant witch. “There must be a Nariyo temple near by. There always is.”

“Ah,” she said. “If you mean the poison well, it’s just down the path. If you say it was a temple — ”

“You just came from that direction. What were you doing?”

She showed him a basket filled with muddy vegetation. “It’s the lilies that grow there, sir. A single leaf is good for a man with a bad heart, and a dried flower will help for rheumatism, and a little slice of the corm, boiled and made up in a tea, will rid a woman of her baby. But you mustn’t drink the water there. It will make you sick to die. I don’t know for what those daughters of sorrow used the well.”

Ah yes, the usual petty wickedness: abortions, sick cows and stunted crops. It wasn’t worthy of an inquisitor’s attention. Her neighbors would take care of her if she went too far. But he wondered if she knew something, an old story handed down from before Lord Agard’s grandfather took possession of the valley. “What daughters of sorrow?”

“The girls that lived there, sir. The girls that died there.”

“Why do you say there were priestesses at the temple?”

“They try to speak,” she said. “But someone bound their tongues long ago. The gods cannot hear their prayers now.”

Raven chose that moment to fling up his head. He did not like standing around. Manvayar urged him toward the track the woman had come along. She stepped aside and belatedly pressed palms to her face in respect.

He could not have said precisely why he stopped Raven again. “The talent for magic,” he told her, “is not a mark of punishment the gods have placed upon children of evildoers. It’s like having an ear for music, nothing more. You can do better for yourself. You are not doomed to a life of sorrow, or insanity, or to commit evil yourself.”

She took her hands from her face and stared up at him, as if he had told her all fish sprouted wings nightly and roosted in trees. “Who taught you that, sir?”

He guided Raven up the track. The wood thinned and soon he saw mossy stonework rising to a ruined wall. An arched doorway opened into a meadow. He looped Raven’s reins around a branch and commanded him, “Wait!”

The first rays of sunlight now slanted across the grass. An ancient scarlet-blooming rose climbed the inside of the wall. The meadow sloped toward a swamp choked with blade-like leaves and tall stalks bearing delicate white flowers. The heady scent of lily overlaid the smell of damp earth and still water.

The witch had dug a muddy hole among the lilies. On the far side of the swamp the slope was steeper, and a stair descended through a tangle of blackberries.

He circled toward that stairway along the high ground and discovered the well itself, a still, square pool enclosed by water-stained Nariyo stonework. On three sides, the marble had been carved into a stylized flower-and-leaf frieze that reflected mirror-perfect in the well. On the side toward the lilies, the wall was low enough to allow amber water to seep from the swamp into the pool.

Manvayar recognized the flower-and-leaf design from Nariyo books and other ruins he had visited. His master had told him it was called maro and was sacred to the Nariyo deity of the same name, goddess of truth and insight. His old master had said maro was not an earthly flower, but now, upon seeing the design side by side with the real lilies in the swamp, it was obvious the two were the same. A temple to Maro had once stood upon this ground.

He squatted and slipped into trance, sending out his soul-touch. Beneath the crumbling walls shone the lattice of power, the ancient foundations of the temple laid with prayer and magic. There were also human bones under the earth, and the stink of necromancy rose out of leaf mold and dewy grass, fouling his nostrils and throat. The smell was old, but there was fresh blood in it.

He steeled himself to pursue that scent to its source, but then a confused image approached the well. He pulled shut his soul-doors and opened his eyes. A girl appeared through another gap in the wall and, holding her skirts, began to descend the grassy slope with care. It was Aleid, the lord’s daughter.

He frowned. She was unaccompanied. “Good morning,” he said.

She flung up her head wildly, startled out of all proportion, and at the same moment lost her footing. With a cry she began to slide toward the well. Manvayar leapt up and caught her arm. “Forgive me,” he said, pulling her to her feet again. “I didn’t mean to surprise you.”

She stared up at him, breathing quickly. This close he could see how perfect her skin was, white and smooth as cream. Her blue riding dress was high-necked to protect her from the sun, so that not even the hollow of her throat showed. Her honey-colored hair fell upon his hand like silk.

Finally she closed her mouth. He let go and backed away. He had no idea what to say. The perfume in her hair clung to his nostrils. He could still feel her warmth on his hands. His concentration was completely shattered.

Another thing he still had not mastered, this paralyzing deluge of the senses. If ever he could find a way to make his soul-doors impervious to the world, ordinary sight and smell would still find their way in. His old master had been right in one thing: only the discipline of the mage could save him.

Manvayar had worked hard to do as his master had ordered, worked to purge all desire from his flesh. But what was possible in solitude at Mount Massaren was not so easy on a summer morning with a beautiful girl beside him.

He looked away for anything at all, and saw that her straw hat had fallen into the well. He scrambled down the bank to retrieve it.

“Don’t touch the water!” she cried in alarm.

He stopped, hand outstretched. “What,” he said, relieved to be offered something innocent to say, “just to touch it?”

“It can poison you through your skin,” she said. “It’s an evil thing.”

He straightened. It was on the tip of his tongue to ask her why, in that case, she had come here, but that seemed too close to asking why she was abroad without a companion, a question that seemed fraught with illicit suggestion. He pulled his thoughts back. “Where does the poison come from? How does it get into the water?”

“It’s a curse,” she said, putting a hand on his arm and stepping carefully down the bank toward him. “Long ago a man ruined a Nariyo girl. She drowned herself in the well. And ever since the water has been bitter poison!” Her hand lingered on his arm. He noticed once again that her wrists were bandaged.

She was as ignorant as the peasant witch. The well was not evil. It did not even appear to be particularly magical, at least no more than the rest of the ruined temple.

Aleid, though — there was something odd about her, something opaque or fragmented to his inner eye.

But now she was close to him again, with her milk-pale skin and the perfume in her gold-streaked hair. She laid her hand on his chest. “Why did you come here this morning?” she asked. “Why do you ask about the well? Do you think the necromancer has been here?”

Her hand crept up to touch his beard, his cheek. “Yes,” he said to the top of her head. He did, very much, want to take her down on the grass and pull her skirt over her cream-white thighs —

With an enormous effort of will, he made his mind pure, cold, orderly, unmoved by the world. The discipline of the mage.

Looking away, watching a stray breeze ripple the surface of the well and blow Aleid’s hat toward the swaying lilies, he recalled that some of the temples to Maro had maintained oracles. The old books said the priestesses drank from the water of maro and read mysteries of past, present and future. That was an allegory, said his master. “Priestess” did not mean a real woman but the purified soul, drinking deeply from divine wisdom.

The amber water of maro, in which no other thing appeared to be living, seeped from the muddy feet of the lilies and drained into the well. There was no allegory here at all, Manvayar realized. The lilies were the poison in the well. The guardians of the oracle had swallowed the poison, and pretended their drunken visions came from the omnipresent eye of the goddess. So much for the wisdom of the vanished Nariyo.

Aleid had pressed her body against his. Now she pulled his head down and kissed him languorously. He felt her tongue slipping into his mouth.

He plucked Aleid’s hands from him, pushed her back a few steps. “Surely your mother will be missing you soon,” he said, as courteously as he could manage.

She flushed a furious red, turned, and ran from him, one hand holding up her skirts, the other covering her mouth. He wondered if the necromancer had sent her to meet him. The distraction had certainly succeeded.

Manvayar urged Raven to a gallop, eager to distance himself from Aleid. The bright morning no longer seemed clean. What had happened upset him unreasonably. Such a sensitive boy — as his older brother had always mocked him.

But there was nothing delicate about hating necromancy, or wanting to purge the world of every trace of its works. Since fleeing Mount Massaren he had burned to do the work of Lord Death, God of Judgment. In that he was strong and certain.

When he reached the manor, Manvayar tended to Raven and then went in search of the Skull Priest. He expected to find Seppan still in bed. Seppan had been a late riser and an excruciatingly slow mover on the trip out from the provincial capital, the reason the journey had taken five days. But as Manvayar came into the stuffy hall, lit now by a single unshuttered window, he saw that Seppan and Lord Agard already held court. Seppan wore full regalia: an embroidered collar and an apron of carved human bones spread across his fat belly and lap.

On a stool before Seppan and Agard sat Agard’s wife. “And then I ran out to see to Aleid,” she was saying in a timid voice. “That’s all.”

Manvayar’s boots rang loudly as he crossed the hall to take up a position behind Seppan. Seppan and Agard frowned at him but did not otherwise acknowledge his arrival.

“You see,” said Agard. “She saw nothing. She knows nothing.”

Seppan said, mildly, “It’s my duty to be thorough.”

Seppan dismissed the lord’s wife and called in his brother. The lord’s brother also claimed to have seen nothing. He had been out on the farms in his capacity as steward when the prince’s messenger been killed. On the day their neighbor Lord Tach had died, business had taken him to the provincial capital.

As Seppan had suggested, Manvayar opened his soul-doors. With distaste he reached out to touch the two unclothed souls, the lord and his brother, with his own naked heart. The brother’s words tasted of truth overlying fear. Lord Agard’s soul smelled of fear also. The fear was in part a fear of discovery, but was otherwise dark and unnamed. Manvayar wanted Seppan to ask the brother directly if he had ever worked necromancy so that Manvayar could smell truth or lie in the denial. But Seppan asked no challenging questions and soon dismissed the brother after the wife.

Next was the brother’s wife, then a plump, elderly nurse. Seppan plied his mild questions. Where were you when the cavalier was killed? And Lord Tach? What did you see? What did you hear?

Terrible screams, the nurse said, her voice trembling. She had looked out the window, seen a cloud, maybe. The cloud rushed upward and she had fainted.

Then Seppan surprised Manvayar by asking, “Do you think the necromancer came with the prince’s messengers?”

Lord Agard chose that moment to shift in his chair. It creaked, causing the nurse to glance in his direction, and Manvayar felt her pull blankness like a shutter over her memory of terror. “It’s better left alone, sir,” she whispered. “Leave wickedness where it lies.”

To Manvayar’s disappointment, Seppan pursued this interesting hint no further. He dismissed the nurse. “Some refreshment, I think, before we continue,” he said to Lord Agard.

It was hardly mid-morning. But the lord called in his servants and sent them for cakes and beer. Manvayar headed for the door.

“Master Duryen!” Seppan called. Manvayar turned. “Now where are you going?”

“Some air,” said Manvayar. The stale air in the hall, together with this touching of other souls, had left him distinctly queasy.

Seppan heaved his bulk out of his chair and crossed the floor. “And where did you go this morning?”

“I rode out for exercise,” Manvayar said. “I… didn’t expect that you would begin so early.”

“Are you a wild man of Tu-shan that you can’t stay under a roof?”

Agard stepped out of the other door of the hall just then. Manvayar said, in a low voice, “I rode down to the entrance of the valley, and found a peasant witch at the Nariyo temple. There is still old power there, and someone has spilled blood recently. I… smelled the necromancer again. I don’t think the witch is the necromancer, but she might know who is. She can tell a mage from an ordinary man.”

He shied away from telling Seppan about his encounter with Aleid. He suspected that Seppan would hold him responsible even if all attempts at seduction had been on Aleid’s side. “I would like to call up and question the dead at the well,” he finished.

Seppan gazed at him. “The exsuscitation,” he said, “is a long way down the road. There are still many facts to establish about these deaths, especially the second one. If you indeed want to be useful to the Temple, you may begin by bestowing upon me the gift of your presence. I trust you have learned that much discipline.”

The fat, lazy priest who could not last two hours without feeding accused him of lacking discipline! But Manvayar suppressed his temper. If his old master had taught him anything, it was that the explanation for a fault mattered absolutely not at all. “I beg your pardon, sir,” he said, bowing.

Seppan shook his head in exasperation. “Go take your air.” He turned to the tray of sweets the servants had brought.

The sun shone brightly, but even in the yard the walls of the manor pressed on him. A groom walked a gray mare whose tail was tied up with pink ribbons — Aleid’s mount, no doubt. Beyond the stables, flush against the wall that encircled the manor, stood an armory and a stretch of practice ground. Manvayar turned in that direction.

Suddenly the oppression in the air condensed into cold threat, and an overpowering stink of rotting flesh rolled over him. The mare screamed and bolted past Manvayar. He spun around. A speck hung for an instant in his vision, then swelled. First it looked like a cloud of bloody pus suspended in water. Then, still growing, it congealed into a tangle of pinkish webbing and glistening limbs. Some of the limbs ended in groping hands, some bore toothy leeches’ mouths.

The exhilaration of pure hatred rushed through Manvayar. The necromancer was here! He narrowed his attention to the width of a sword blade, reached to the roots of his soul and ripped out a piece of his own substance, which he formed into Nariyo words of command and hurled at the creature. The words sank into its flesh. It thrashed but kept swelling outward until it was twice as high as a man and its limbs writhed toward the manor windows.

A man was screaming. Inside the stables, horses whinnied and crashed against their stalls. The stench of putrefaction choked him.

Manvayar took a few steps forward, rounding the corner of the stables. The thing had pinned the screaming groom to the ground. Fingers thick as cucumbers gouged out his eyes, and the man’s bloody liver lay discarded on the stones. Now the creature looked like a strange tree precariously rooted in the groom’s body; agony fed the thing and made it branch and leaf into flesh. Its topmost limbs reached the manor’s second story.

Manvayar took a few steps forward, rounding the corner of the stables. The thing had pinned the screaming groom to the ground. Fingers thick as cucumbers gouged out his eyes, and the man’s bloody liver lay discarded on the stones. Now the creature looked like a strange tree precariously rooted in the groom’s body; agony fed the thing and made it branch and leaf into flesh. Its topmost limbs reached the manor’s second story.

Manvayar saw Aleid, hands over her mouth, at a window above him, and he was suddenly afraid the monster would seize her as it had the groom.

His sword was already in his hand. He slashed at the limbs tearing at the groom. Blue light leapt from the sword and the severed pieces shriveled like hair in a candle flame. The power coursed out of him now. Elation filled him as he felt his strength.

The divine, the source of all grace and power, is both below and above; that was what the Nariyo had written. Manvayar reached into the dark labyrinths of his soul and stretched upward into the clear sky, and for a moment he felt as big as the world and bright as the sun. He slammed his sword down upon the top of the monster. A lightning bolt crashed through him and exploded.

Then the courtyard was empty, the stink gone. The creature had vanished. Exaltation crumbled away, and he was only himself. He leaned on his sword, shivering and ill. He began to be aware of other sounds: dogs barking in a frenzy, muffled shouts from the house.

The groom at his feet moaned. Manvayar wondered how the man could remain alive in his half-dismembered state. He suppressed nausea with great effort. Seppan was right. This necromancer had no finesse — only ferocious hatred.

Then people stood around him: Lord Agard, Avan, Seppan, the Sun Priest mumbling prayers. “Go on!” commanded the lord. A man-at-arms swung a battle-axe upon the groom’s neck. Blood flew as the axe struck paving stones.

Manvayar looked away, looked up. Aleid no longer gazed from the second story.

Chaos in the house: servants milled, women and children wailed and sobbed. They shrank from Manvayar as he stalked the corridors, searching for the window Aleid had watched from.

He found it in her bedchamber, where Aleid herself lay in screaming hysterics. He pushed aside an elderly maidservant who tried to block his entry, pulled Aleid by the wrist from her bed, and flung the contents of a pitcher over her head.

The screams stopped instantly. She stared at him in terror. “What did you see?” he demanded. Water dripped from her face but she made no attempt to wipe it away. Her pupils were dilated so wide that her eyes looked black.

“What did you see?” he said again through gritted teeth, shaking her. Now he had blood all over his hands. She bore a deep gash on her wrist. “You must have seen what happened! Who was there?”

More women flapped around him, squawking. He shook them off. Aleid began to sob. “I didn’t — ” she gasped. “I didn’t see — ”

The door opened with a crash. Manvayar half-turned; Lord Agard and his son stormed in.

“What in the Bright Lord’s name are you doing in my daughter’s bedroom?” Agard shouted, purple with rage.

“Questioning her, sir,” said Manvayar coldly. “She saw what happened better than I did.”

“She’s a precious little vixen,” said Agard. “That’s why she’s carrying on. Now, I don’t care if you are king of Nariyo wizards — get out!”

“You can’t hide what you know about this,” Manvayar said, temper rising. “Do you think you can keep secrets from the Temple of Judgment?”

“That’s enough!” cried Seppan, from the door. And he said a word.

For a moment everyone in the room froze: weeping Aleid clung to her father; the mother embraced her daughter, bloodying her dress; Agard and Avan glared in fury. Then Manvayar mastered his anger and bowed to Seppan. He stepped past Avan into the corridor.

“What did you think to accomplish by that?” It was Seppan’s turn to lose his temper.

“The girl saw the whole thing from the window,” Manvayar said. “And there’s more.” He showed Seppan the blood on his hands. “I think the necromancer has been using her to call up his power – he’s preparing to eat her soul too.”

“It isn’t time to question her! Haven’t I told you to stay away from her? Do you have any self-control?”

Manvayar poured water into the basin and washed his hands. “I don’t understand,” he said. He stripped off his shirt, and then the singlet beneath, both splattered with the groom’s blood; as long as he was in a rich man’s house, let the servants wash them. “You know as well as I that everyone here is hiding something. But you don’t press them. I’ve twice smelled the necromancer at that ruin, and you don’t even want to investigate. How many people are going to die – how many times is the necromancer going to feed and strengthen himself, before we make any real effort to unmask him?”

Manvayar had not raised his voice. He was not going to give Seppan further cause for remarks. He pulled on his only spare singlet and shirt and turned again to face the Skull Priest.

Seppan, seated on the bed, had spilled his divining bones from their cloth bag onto the covers. He said to Manvayar, “My actions are not arbitrary. The Temple has procedures, based in long experience, that govern my actions. Experience that I need remind you, you utterly lack — ”

“Yes,” said Manvayar. “But at the well — ”

“The first manifestation was here, at the manor, wasn’t it? The prince’s cavalier. And the second time, too. The neighbor-lord. And today, the groom. All three times in the manor stable yard. Don’t you think this is significant?”

“But why not act now?” Manvayar asked. “The necromancer will be tired from sending out his power. He will have lost power because I destroyed his creature before he could eat a new soul.”

“Young man,” said Seppan, “it is a pity that the guidance you have received is hopelessly unequal to your talent. Your magic is like a thunderclap deafening everyone in the neighborhood. It has deafened me. Listen: an inquisitor is not just an arrow speeding toward the heart of truth. The task is not just to discover the necromancer but to undo his work. To give over to Lord Death what is His due. We will not repair the balance of the living world by overturning everything in sight. Patience, please, patience, patience, patience.”

He turned to his divining bones, closed his eyes and slipped into trance. Bitter contempt filled Manvayar. Seppan talked as if a hunt for a necromancer were a suit at law, a plodding through words and facts like a peasant through a field of mud. He had expected the priests of the God of Judgment to be as keen on the trail as a pack of hounds, and as merciless with their prey.

Seppan began to chant in an almost inaudible monotone, tossing the carved finger-bones from hand to hand. Manvayar turned away, pacing to the window, to the door, to the window again. His old master had thought all such tools, bones or playing cards, gems or mirrors, to be the crutch of a weak talent. The ancient ones, he had said, had drunk from maro, the pure spring of divine truth. Find that spring within yourself and nothing in the universe will be hidden.

But his old master had proved to be a secret necromancer.

And maro was only a poisonous weed.

Truth, though, divine truth: Manvayar knew what that was. Truth was a quarry and you hunted it to the kill. It was the whirlwind that tore down the walls concealing evil. It was the blinding flash of insight that in a white-hot instant reduced all deception to ash.

He wanted to be the hound of the God of Judgment. He wanted to open this suffocating stone tomb of a house to the sky and cleanse it with fire and storm. Everything else was just words, hypocrisy, delay.

“I see you are of no mind to attempt self-discipline,” said Seppan, looking up from the scatter of bones upon the bedcover. “If you can’t be still, please go out and prowl around the countryside again. Perhaps that will relieve your restlessness. But for everyone’s sake, stay away from the girl!”

Manvayar suppressed another blaze of anger. Seppan had no idea of the disciplines to which he subjected himself. The nightmares he kept locked up, the desires — if he had been his brother he would have taken Aleid this morning without a thought.

He bowed with utmost politeness. “I am your servant, sir.”

Manvayar took his sword outside to the practice ground beyond the stables. The guards had carried away the groom’s remains, and a pair of terrified kitchen servants now sloshed water on the pools of blood.

He cleaned a layer of ash from his sword, all that was left of the necromancer’s creature. Then he swung his arms, working at tightness in his shoulders. He had hardly trained in months, not since leaving Mount Massaren. And then to spring into violent motion —

He stretched arms and legs thoroughly. Then he stripped off his shirt and singlet and began to pace through the first of the Thirty-Nine Courtesies of War, starting, as he always did, on his right and weaker side. He left soul-doors ajar to warn him in case the necromancer again summoned his creature.

Exercise was a fine idea. He had been far too sedentary lately. Manvayar moved onto the Second Courtesy and then the Third, with its demanding deep stances and pivots, and he did feel his mind settle, his anger dissipate. Seppan had been right to chastise him. He did not have self-discipline. He had let emotion spur him into wild and ill-considered action.

Exercise had always calmed his thoughts. Even his old master, no man of war, had approved of the discipline of the sword.

Perhaps, though, if that mage had understood there was pleasure in breathing and sweating hard, and pushing your muscles to the limit, he would have forbidden it.

After a while, he saw Avan approaching from the house. Manvayar wondered why Avan would venture into this courtyard where the power of the tormented dead had so recently flowered — unless just to show he was not afraid.

“Well, look at our left-handed boy,” Avan said, when he reached the practice ground. “He really can use his stick like a man.”

Manvayar began the Fourth Courtesy, with its three imaginary opponents. His muscles were already aching and his wind shorter than he could remember. Sweat poured down his skin.

“A swordsman and a mage,” Avan said. “And a man of very few words. You must be useful indeed to the Temple of Judgment. I hear you dealt impressively with the necromancer’s monster. Thunder and lightning! But you weren’t quick enough to save that poor groom, were you?”

Manvayar longed to switch his sword to his left hand and show this swaggering provincial what real sword-work looked like. Instead, again remembering Seppan’s advice, he reluctantly extended soul-touch toward Avan. He tasted not only the hostility that was obvious, but jealousy, which surprised and puzzled him. Beneath that was a powerful fear, not only of what had happened, but of what the truth might turn out to be.

“You have an eye for my sister, left-handed boy,” Avan said. “I’d look elsewhere if I were you. There is nothing unclean in our house. No necromancer could live here and we not know it. Are you and that priest too stupid to notice that the evil only comes when we have a visitor?”

An interesting point, thought Manvayar, but so was the corollary: it’s always the visitor who is killed.

Until now. Except for me.

Manvayar labored, his sword whining as he cut one Diagonal after another. “Do you have anything to say for yourself?” Avan said.

“I prefer,” Manvayar panted, “to save my breath.”

He did not need to be watching to taste the surge of hatred those words caused. “Remember what I said,” Avan told him, and he stalked back to the house.

Exhaustion forced Manvayar quit soon after that. He stretched arms and legs again, then grabbed his clothing and returned inside. At the top of the stairs that led to the bedrooms, he passed Aleid clinging to a maidservant. Aleid’s face was blotched and red from tears. When she saw Manvayar, she shrank back, pressed her face into the servant’s ample bosom. Embarrassment flooded him. He had forgotten he was in a house with women, and here he strutted half-naked and sweating through the hallways.

But then he noticed again how she presented a confusing picture to his inner eye, almost as if she herself wore a wizard’s mask that prevented any leakage of self into the world.

The mask was not complete. It was less a blank outer shell than a cloak sewn with fragments of a mirror, each reflecting in a different direction. Each showing a different piece of her, and perhaps every one of them a false image.

“Can you tell me, sir,” Manvayar asked Seppan, as he sponged sweat from his skin, “what sort of man was the prince’s messenger, the one who died here?”

“I didn’t know him.” Seppan had finished divining and now gazed out the window.

“There was nothing more than his name in the Temple reports I was shown,” said Manvayar.

“There were no other reports.”

“A young man? Old? Nobly or base born?”

“Don’t tell me you have been thinking,” said Seppan, turning. “What sort of man would you expect?”

“Well-born,” Manvayar said, “but not rich. A younger son in need of a patron, maybe. Presentable, but not too smart — or the prince would have him at some other task.”

“In other words, someone like yourself,” Seppan said. “Only more personable and better dressed.”

Manvayar eyed Seppan, wondering if the inquisitor were being humorous.

“Go on,” Seppan said, encouragingly. “What else have you been thinking?”

“That I might have been the necromancer’s intended target today. As you perhaps have noticed, I wear protective spells. In case my old master is searching for me. It would — they would deflect such an attack.”

“Ah,” said Seppan. “And the necromancer’s second victim? Another handsome young man?”

“He was a suitor.”

“And where,” said Seppan, “is this train of thought leading us?”

“The girl,” said Manvayar. “Aleid.”

Seppan raised an eyebrow. “You think she doesn’t like young men who admire her, and she kills them?”

It was on the tip of Manvayar’s tongue to tell Seppan the girl was a whore who would lie down with anyone on sight. “I think,” he said, “someone else might not like them.”

“Well, perhaps we should put more spells on you,” said Seppan. Manvayar still couldn’t tell whether he was serious.

At first Manvayar slept heavily. Then he began to dream about journeying with his old master to a Nariyo ruin. A sound woke him, footsteps tapping softly past the door. They faded into silence.

After that he lay awake for hours. Now he could not stop thinking. He thought about everyone he had met since their arrival. None of them, except the peasant witch, had any magic, and he doubted she was powerful enough to hide binding spells from both a Skull Priest and a mage, even a mage as stupid as he.

Then he began to think about Aleid, and to wish he had taken her at the well, beautiful Aleid with her perfumed, honey-dark hair. She wanted him, the whore.

Then he thought: she was bait. He had been right in the first place.

And he began to wonder if he was smart enough to get out of this house alive.

He opened his eyes to find his old master above him. A spell crashed around him like an avalanche of stones, thrusting him toward darkness.

His own cry startled him awake. The first light of day seeped into the airless room. He dressed quickly, took his sword, and headed down to the stables.

Soon he and Raven cantered through the sweet morning air. The lane they followed ran beside a stream. The stream was clear and deep, perfect for swimming. Manvayar began to look for a place to get down to the water. When the lane veered from the stream, he guided Raven along a narrow track that clung to the bank.

But the track wound through increasingly tangled brush until it reached a wall of fine mortised Nariyo stonework, and then it, too, bent away from the stream, following the wall upward, and then they were at the ruined temple again.

Today a thin sheet of clouds covered the sun. There were no shadows in the forest, only a green dimness that brightened slowly as he and Raven rode into the meadow surrounding the poison well.

Manvayar’s bones prickled as he rode across the temple’s foundations. A faint reek of necromancy mingled with the lilies’ perfume. He was suddenly sure he was not alone. He dismounted and walked to the slope overlooking the well, extending his soul-touch outward.

And found cold danger.

He drew his sword and spun around. A cloud of bloody pus leaked into the air, flowering into wet flesh that billowed outward. Stench blasted him in the face. Sticky-slimy fingers grabbed his sword hand, and fiery numbness shot along his arm. Shouting Nariyo words of command, Manvayar stumbled backward. The numbness scorched through his whole body, paralyzing him. He felt his power shooting toward the creature, but no ground lay beneath him.

He was falling.

He smacked into cold water. His boots filled and he sank like a stone, unable to move. A bitter taste filled his mouth. The light dimmed as he sank, but he could see skulls lying in the brown depths below him. The old temple magic scratched at his bones.

And then his feet touched bottom, and the paralysis broke. Skulls crumbled under his boots as he shoved with all his strength. He shot upward, desperately groping toward air. He broke the surface and choked and coughed as he floundered in the water, searching for the necromancer’s creature.

It hovered over the meadow, not much larger than a horse. His words had injured it and it had not yet fed anew. Its toothed hands groped at the edge of the swamp, but it did not seem to be able to cross the poisoned water. Manvayar hauled his feet onto the submerged stones dividing well from swamp, and he pulled himself to a standing position, hacking water from his lungs.

He reached with one hand into the bright arch of the sky, and the other into the murky, brownish depths of his soul. And, coughing out Nariyo words of command, he squeezed a piece of himself into lightning. The monster burst apart. Gold-lit ripples spread across the water and died.

The meadow was empty.

Manvayar waded to the edge of the meadow and crawled onto the bank. There he jammed his fingers into the back of his throat, and hot bitter water roiled up from his stomach. Again and again he forced himself to vomit, until, panting and coughing, he could heave only bile.

He collapsed onto the grass, though he knew he didn’t dare rest long. The necromancer might still lurk nearby, and if Aleid was right and the water could sicken a man even through his skin, he needed to seek out Seppan right away. The inquisitor would — Manvayar hoped — know magic against poison.

But he was drained and sick, and sluggish from exhaustion. Calling out lightning twice in two days had used up too much of him. A mage’s living soul could regenerate, but not this quickly.

His heartbeat drummed in his ears. He could hear a murmuring and crying like a distant flock of birds. It seemed to come from all around, from under the swamp and the meadow and from under the roots of the trees beyond. He pushed himself into a sitting position but he could not spy what made it.

He emptied the water from his boots and pulled them on again. Then he saw that his sword had tumbled down to the water’s edge. He crawled over and grasped it.

His sword looked very strange. The blade shimmered, and the scarred pommel glowed like precious wood. As he peered closer, he was surprised to see what a beautiful thing his hand had become: long slender fingers, tendons taut as bowstrings, fine hairs glinting like gold — even the rough nails, even the scar on his thumb seemed to have been perfectly sculpted.

He rose to his knees and sheathed his sword. Movement on the surface of the well caught his eye. He leaned closer. It was himself mirrored in the dark water, framed by white lilies and luxuriant grass. His face surprised him, too. His short hair and beard shone pure gold. His eyes were the blue of the zenith at evening. He had never thought of himself as handsome like his brother, but the well showed him a face that was pure and merciless as an angel’s. Except those eyes: they were haunted and sad, tender. He had always hated his tender heart, so easy to wound, so difficult to master. The bitter taste of the well filled his mouth. He spat into the water and shattered the angel’s face.

He pushed himself to his feet and unsteadily climbed the slope toward Raven. The crying grew louder as if the distant flock approached. He looked up, half expecting to see cranes settling in the high canopy of the forest. Trees spun lazily over the meadow. The meadow heaved and undulated as if something tried to force its way out of the ground. The bird-cries sounded almost like speech.

At last he realized the poison was already working on him. But his thoughts had slowed, curdling into impenetrable clumps.

Then the earth did split open. Girls’ heads sprouted out of tumbled dirt and grass, out of mud and swamp water. Iron spikes fastened their tongues, and blood spilled from their mouths as they struggled to speak, keening wordlessly like a flock of seabirds.

Their torment arrowed straight into his heart. Manvayar tried to slam his soul-doors, but could not find them. He might as well have been born naked.

Dark-haired and blonde, the girls clawed their way out of the earth. Chains bound their wrists, too, and linked the spikes that pierced their hearts and bellies. The girls floundered in the upturned clods, splashed in the well; mud covered their bloody shifts and bruised flesh.

Manvayar tried to step backward, but they crowded around, crying, lifting their thin shackled wrists. Their faces pleaded with him. It was as if his own gut was pierced by burning metal, his own bones hammered through with iron, as if he himself had been buried a hundred years, yearning for breath and a release from pain. Anguish filled him until he thought he would shatter. To free them he reached for splinters of bright sky with one hand, but there was nothing left in the well of his soul, so he seized his own aching guts, tore out his heart by the roots, and ripped himself apart in all directions.

Trees crackled with lightning. The air exploded into a billion glittering motes. The crying girls blazed with light, and their shackles burst into flame and vanished.

And then fire and thunder rolled away. Manvayar found himself on his knees in the mud. The girls wore plain blue robes now, and they flocked around him. They opened their mouths.

The earth said

MARO

The priestesses said

MARO

The meadow, the forest, the gray sky rang with light as if they were a gong struck by a god.

Do you seek the truth? The priestesses said to Manvayar. Do you want to serve your god?

They showed him:

Smoke and fire pour from the white-walled temple. Here rides a lord and his handsome sons in golden armor. Velvet ribbons fly from warhorses that prance daintily through pools of blood. Here follow Sun Priests who hold aloft their rayed scepters, chanting. Here is the cloistered garden with its pool of lilies. Here, cornered by fire and red-spattered soldiers, huddle the Nariyo seeresses and the old women who care for them.

Now the lord and his sons dismount onto spurred and booted feet. A word from the lord: the old women are put swiftly to the sword. Another word: soldiers bind the girls and drag them to the well, and forcing their mouths open, they pour in the amber poison, helmet-full after helmet-full. The lord takes first pick of the girls, and then the sons choose, and the soldiers make do with the leavings. Smoke billows into the evening sky while the Sun Priests chant prayers to shackle evil and imprison it forever. When the soldiers are finished the lord orders them to use their knives.

We did not die quickly, the girls told Manvayar.

We were bound in our torment.

They bound up our pain and our magic. They chained us here, in the living world.

He looked down and saw blood runneling across the mud; he saw naked bodies floating in the water and scattered over the meadow. In terror he again jammed his fingers into his throat, but nothing more came up.

We only drank an eggshell’s worth to see what is hidden, the priestesses told him in their bird voices.

The water of truth is strongest at the bottom of the well.

So much will make you sick to die.

He struggled to his feet again, wondering if Seppan could still save him. The priestesses became bones standing there. “Raven!” he shouted, stumbling up the slope. “Raven!”

But what he found was beautiful Aleid, with her honey-dark hair, her cream-white skin. “How could you free them?” she screamed.

Ghosts cried in his ears, Do you want the truth?

A man drags Aleid to the well, and the man is her father, and he beats her until her face is bloody, calling her a whore. And holding her nose to force open her mouth, he pours in a cup of poison. She chokes and sobs. He throws her to the ground and rides away.

We served the oracle for a few years only, the girls told Manvayar. They never gave the water to a woman of child-bearing age.

Aleid sobs while the poison takes her. She moans, writhes in pain, grips herself between her thighs; when she draws hands from under her skirts they are red with blood, and she wails, wails, wails.

“Stop!” Manvayar shouted at the ghosts, even though he knew they alone weren’t the cause of these visions. It was the poison, and insight hidden like old bones in his murky heart.

This is the truth, the girls said.

Aleid wails, she screams and sobs in terror. Poison eats into her soul and opens doors she had not been born with. Bony ghosts crowd on that threshold.

We were hungry for blood and pain, the priestesses told him.

We wanted to remember what it was like to live, they said.

We wanted her to give us vengeance.

“Raven!” Manvayar called out. He lost his balance and grabbed Aleid’s arm. She had hiked up her long sleeve to the elbow, exposing rows of cuts on her arm, some freshly scabbed, some old wounds. Her blood welled around his fingers.

You wanted truth, said the priestesses.

A solitary girl descends to the well and cups her hands to drink the poison. With a knife she slashes her arm. And while the hungry ghosts gather to feed, she eats in her turn as much of the power of the tormented dead as she can swallow.

She was hungry for our pain too, the ghosts said. She thought eating us would make her strong.

But what happened here was stronger than she was.

“You can’t make me see these things!” Aleid screamed at Manvayar. She pulled out of his weakened grip and ran.

“Stop!” he shouted. And then, in terror, when he found the earth rushing toward his face, and he was no longer strong enough to push it away, “Help me! Help me!”

What happened here is also stronger than you, murmured the priestesses of Maro, those daughters of sorrow.

He slid down through the earth as if it were brown viscous water. He tried to draw a breath but soil poured into his lungs, stone plugged his throat. He wanted to beg Aleid for help once more, but he could no longer move his lips. This time he knew he would never swim back to the surface.

But then a powerful soul-touch hauled him upwards. A word lanced through him. His scream of agony pushed through the soil choking his throat until hoarse and curdled sound burst into air, and breath rushed back into his lungs.

And then the tumult of the poison, the terror and panic, all receded into silence. He lay there gazing at the clouds, panting, too weak to move.

Hands pulled him mercilessly to a sitting position. “You’d best get on your way, sir,” said the peasant witch.

He had thought it was Seppan who had banished the poison. “Where’s Aleid?” he croaked.

“I didn’t save your life to keep you poking your nose where it doesn’t belong,” she said. “You go finish what you started. You send those girls to Lord Death for their judgment. You can’t leave such as them to wander the country of the living.”

He rolled onto his hands and knees.

Raven galloped up the lane, Manvayar clinging to the saddle with all his strength. The poison had ebbed, but at the edge of his vision Nariyo bones rose out of fields and ditches and cried to him, They murdered us for our land. On the far side of the village he spied Aleid’s gray mare ahead of him. Aleid, glancing over her shoulder, began to scream. She urged her own mount to a gallop, but too late; Raven was already closing on her. Her hair and gown flew behind her as they climbed the hill.

Guards at the manor gate jumped from Raven’s thundering hooves. Manvayar slid to the ground and stumbled up the steps, following Aleid through the manor door. The guards tried to stop him, but Raven reared up, screaming louder than Aleid, and scattered them.

Dizziness claimed him for a moment. Next Manvayar found himself in the airless hall, and the lord in his velvet robe gripped one of Manvayar’s arms, and his gray-bearded brother had the other, and here was handsome Avan in shirt and breeches and sword. A fist fell like a hammer on Manvayar’s chin. Aleid screamed, “He drank the poison! He freed the ghosts! He’s trying to kill me!” Another fist smashed into Manvayar’s nose, and blood filled his mouth.

The rabbity Sun Priest, rayed scepter held aloft, began chanting prayers to bind evil.

Manvayar gasped, “The Skull Priest — ”

The next blow slammed into his gut. He doubled over, retching. Avan grabbed him by the hair and hauled him upright. “The Skull Priest,” he mimicked. “Did you think you would find the necromancer by drinking poison?”

The first threads of the Sun Priest’s spells floated onto Manvayar like spider’s gauze. He did not try to brush them away. Beyond his weakness and the pain of Avan’s blows, a strange bright clarity was rising in the emptied well of his soul.

Avan drew his sword. “Did you discover the truth?” he taunted, pulling his sword back for a killing thrust.

The clarity spilled through Manvayar’s senses, bitter as the amber poison, only this water was pure, it was as bright as sunfire and as sharp as broken glass. The brilliance burned his eyes, his guts, his very thoughts. It was as if a conflagration blazed through the manor hall itself, smelting stone walls and human souls alike to perfect transparency, and shining onto all that had been hidden inside.

Manvayar had not been able to prevent his old master’s escape from the inquisitors. But he would bring judgment on this evil.

He said to them, rage scalding his mouth, “Do you want to see the truth?”

The old lord pushes up Aleid’s skirts, spreads her knees and mounts her. He has cast his velvet robe aside on a nearby chair, and now his pimply buttocks clench and heave away. But Aleid’s face is hardest for Manvayar to look at, pretty Aleid, her eyes squeezed shut into emptiness.

Aleid whimpered. Avan grabbed Manvayar, threw him against the wall, raised his sword higher. “Stop the sending. Stop this lie!”

“I’m showing you the truth,” Manvayar said.

Avan slides his hands into Aleid’s nightgown, squeezes her breasts, pushes her against a wall. She looks away. “You whore,” he whispers. And he rakes up her nightgown, lifts her bodily, and shoves himself into her.

Sobbing, Aleid collapsed to her knees. Avan’s arm, poised for the thrust, began to shake.

“You don’t want to know the truth?” Manvayar asked.

At dawn a cavalier slips from Aleid’s bedchamber. She sits in the disordered bed and gazes into emptiness. Then she takes a knife and draws it across her scarred arm, one slow cut after another, each deeper than the last. Blood spills onto her white nightgown. At last she rises. She unlocks a trinket box and removes a bottle of amber liquid, from which she fills a small cup. As she drinks, she looks out the rusted window that does not open. And then her breath catches, she sees something below, she blazes with anguish and loathing. Outside the window, a man begins to shriek in mortal terror —

Avan struck Manvayar over and over. The lord shouted at Avan, the uncle shouted, Aleid sobbed in huge shuddering gulps. Then a deafening word of command rang through the room.

STOP!

Everything stopped. Hands fell away from Manvayar and he had to clutch the wall to keep his feet. In the silence he heard Avan’s sword tip grate on the floor.

Fat old Seppan waddled across the hall. “What in the name of Lord Death is going on?”

“Your servant drank from the poison well,” said Lord Agard. “He’s dying.” He spoke imperiously, but sweat shone on his gray skin.

Anger suffused Seppan’s face. “And what did you learn there?” he said to Manvayar, voice rising.

“There’s no point in talking to him,” said Lord Agard. “It’s an act of mercy to put him out of his madness.”

Seppan ignored the lord. “What did you learn from the poison? What did you learn from the ancient wisdom of the Nariyo?”

If Seppan had not laid the word of command so heavily upon him, Manvayar would have showed Seppan what he had showed the others. He opened his mouth to try to explain it in words, but the Skull Priest kept berating him, not even pausing for breath, and then ghosts crowded into the hall beyond Seppan, dead girls in blue robes. Aleid was the only one who noticed them. Other than the Sun Priest, who was watching the inquisitor, she might have been the only member of the lord’s household who could see them. Her sobs were small and desolate at first. The priestesses slipped to her side and whispered in her ears, touching her hair and skin. She shrank into herself as if she lacked the strength to pull away, as if there were no other place on earth to go.

“They’re here, master,” Manvayar said. “From the temple.”

Seppan shouted, scarlet, “Didn’t I tell you to keep away from there? Should I even try to save you from your stupidity?”

Manvayar had coursed after truth like a hound on a blood trail, and he had at last hunted down his necromancer. Surely Aleid deserved to die. She was fated to die by decree of the Temple of Judgment. But the sight of her crying, hugging herself with bloody hands, taught him that he was after all no merciless hunter. He was just a left-handed boy with no skin over his heart. The vision of Maro is bitter as poison, and sharp as broken glass.

Aleid sobbed now with pain and effort. Bloody pus leaked into the air above her head, flowered into wrinkled mouths and groping hands. Manvayar reached for power to throw, but he had nothing left, and Seppan’s word of command still weighed on him. “I can’t stop it,” he said. “Master, you have to.”

At last Seppan stopped shouting at him long enough to take notice of the monster and the ghosts. Surprised, the priest turned to face Aleid, raised his fat hands and spoke another word of command.

Aleid flinched as if stabbed. The word seized the creature and it began to shrivel. But the dead girls kept touching her, whispering and pointing to her father and uncle and brothers, the blood of their murderers. Aleid shook her head, sobbing, while her tears spilled and her eyes squeezed shut into emptiness. The wrinkled flesh sent down roots into her heart, her belly, between her thighs. More pus and blood flowed into the air and congealed into more burrowing, thrusting, feeding roots and groping hands. Seppan began to chant a prayer to the God of Judgment.

Maro had burned the world clear as glass: Manvayar could see that this time the creature was not necromancy. He had unshackled the dead priestesses, so Aleid could no longer use them for her magic. This time she fashioned the monster out of her own fractured soul. The ghosts were urging her to avenge her torment and their own, but she did not send the monster to destroy her father or her brother. She fed it herself instead.

Lord Agard stared at her, gray-faced. Manvayar looked the lord and his brother and his strong-boned sons, at their rich clothes and their pride and vanity and fear, and he knew what was going to happen:

“She is the necromancer,” Avan said, amazed. And he plunged his sword toward his sister’s back.

Manvayar managed to draw his sword in time, and using his left hand, his true hand, he lunged forward to knock aside Avan’s blow. Avan turned and thrust swiftly at his heart. Dizziness swung over Manvayar, weakness unhinged his knees, but he dropped beneath Avan’s thrust and swept his own sword under the other’s arm. The blade bit deep, and Avan staggered backward.

Lord Agard shouted. Avan’s younger brothers leapt forward, swords out. The noise of metal clashing and men yelling rang through the hall. Manvayar slashed the youngest boy across the hand, and that sword skittered onto the floor. Avan came in again, big, powerful, quick even wounded. The lord himself swung a sword at Manvayar. Manvayar tried to stay between them and Aleid, parrying, striking. She might be fated to die, but he wouldn’t let them be the ones to kill her.

He saw Seppan, untouched by the creature’s groping hands, and he saw a steel-sharp fissure open in the world as Lord Death reached down to answer Seppan’s prayers, and destroy the monster.

But as cold swirled out of that fissure, the ghosts surged to its brink. The dead girls began praying to Lord Death, and their wild keening drowned out Seppan.

What happened here is stronger than any of you, they told Manvayar.

We will have vengeance any way we can.

Didn’t you long to be the God of Judgment’s champion?

And then a steel-sharp hand seized Manvayar. Ice ran through him like fever. He flew like an arrow of darkness, exploded like a bolt of fire, roared like a whirlwind across a plain. Bird voices cried in the whirlwind, and white birds tumbled like scraps of paper into an abyss of light. He soared after the priestesses, but a cold hand tossed him roughly back.

And he stood in the hall again, trembling and sick from the touch of the god.

The ghosts had vanished. The monster had disappeared, too. The Sun Priest knelt in terrified prayer while the guards and servants cowered at the doors. Clutching his injured hand, the youngest boy huddled behind an appalled and grim-faced Seppan.

At first Manvayar wondered where the others had gone. He had to look down to find them: Lord Agard, his brother, his sons, their blood still pooling across the floor.

Their blood on his sword. On his clothes. Lord Death had exacted the dead girls’ vengeance, He had put on Manvayar like a glove to do His work.

Manvayar had wanted judgment. But he had not known what it would be like.

“Manvayar,” a girl’s voice said.

Aleid lay at his feet, her breath coming in short gasps. She looked as transparent as a ghost herself. With enormous effort he knelt and took her hand. “You are a seer,” Aleid said. “Will the Sun take a girl like me?”

Before Manvayar could answer, Avan said scornfully, “You?” He sat slumped against the wall, hand in his armpit. “The Sun will not want you, sister.” The words made him cough.

“The Sun is merciful! The Bright Lord is merciful!” Aleid said. But Avan did not hear her. His last cough hacked up a river of blood, and in another moment he was still.

When Manvayar looked back, Aleid had gone as well, smoke in the wind. The insight was fading in him, and he could not see whether Lord Death delivered her to brightness or retribution.