The Poison Apple: What do The Watchmen, Sandman, Frankenstein, Dracula, H.P. Lovecraft and Sherlock Holmes have in Common?

Leslie Klinger in Sherlock mode

An Interview with Leslie S. Klinger

Crowens: What drew you to the Victorian era? That seems to be the common thread for most of your books except for your annotated graphic novels.

Klinger: When I was young, I was a big science fiction reader. In my second year of law school, my girlfriend bought me a copy of the William S. Baring-Gould Annotated Sherlock Holmes. I was hooked. Like most people, I probably read one or two stories as a kid, paid little attention to them, and wasn’t really interested in mysteries. Then I started reading this, and I enjoyed the footnotes — the idea that there was this scholarship. One of my responses to the Baring-Gould edition was a weird one: Some day when I’m old and retired, maybe I’ll be the person who will update it. I became immersed and decided I was going to become a Sherlockian.

In 1976, there was a classified ad in the Baker Street Journal placed by somebody selling his collection of 300 books, a real collection, not like the junk I’d been buying. It was very expensive… like thirty-five hundred dollars. I talked it over with my wife. For that time that was a lot of money. She said, “You’re the kind of person who should be a collector. Go for it.”

Suddenly I had the core of a really good collection and became known in some small circles as a nut about Sherlock Holmes. I started giving talks about Sherlock Holmes, and I got invited to a dinner at the BSI back in 70s. It was one of those bucket list things where I never thought about it again. In 1995 a friend arranged for another invitation. I went to the dinner, and I haven’t missed one since then.

In the mid-nineties, after I annoyed her one too many times with a suggestion that we make “plans,” my wife said, “You have all those books. Why don’t you go write something?”

And I thought about it, and frankly the thought had never occurred to me. Over the years, I had written tax-related and estate planning articles, because that’s what you do if you’re a lawyer interested in your profession, but it never occurred to me to write anything about Sherlock Holmes, even though I’d been reading the Baker Street Irregulars Journal. So, I tried my hand at it and started writing some articles, and they were published.

It was clear after forty years that the Baring-Gould annotated version of Sherlock Holmes was going to need a new edition. It was sort of a mild fantasy that I’d be the one to update it, but in the mid-nineties I said to myself, “Well, why do I have to wait until I’m old and gray? Why don’t I start doing this one story at a time?” In my first few efforts, I literally typed out the original material and then added on material at the end of them. I did one or two stories that way. When I showed them to my friend, Christopher Roden, he said, “You don’t have the rights to the Baring-Gould annotations. You can’t just use them.”

My reply was, “Oh, I guess that’s true.” So, I had to do something else, and he gave me a whole sheet of notes on it. That’s when I started doing a few stories at a time.

Steven T. Doyle and Mark Gagen, who had bought what is now Wessex Press, said to me, “Gee, these are really good. Let’s publish them. But let’s do it more organized and start with the Adventures of Sherlock Holmes first.”

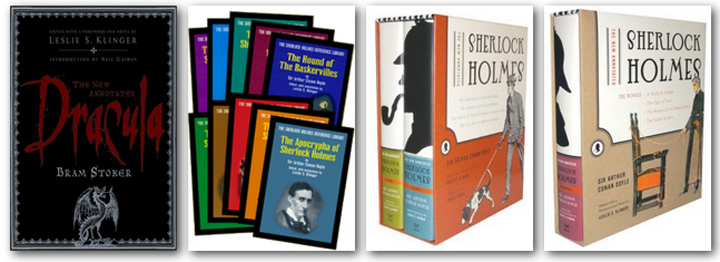

I agreed, and that became the first volume of what is now known as the Sherlock Holmes Reference Library. That came out in 1998. People liked it a lot but commented that my writing style resembled a law review. They didn’t mean it as a compliment. What they meant, quite correctly, was that there was one line of text, and the rest of the page were footnotes.

Then in 2002, out of the blue I get a call from Bob Weil who is a senior editor at W.W. Norton & Company. He said to me, “We want to do a new edition of the Baring-Gould books, and we hear you’re the guy to edit it for us.”

I said, “Really? You’re going to pay me?”

That book came out in 2004 and 2005, and I won the Edgar Award (sponsored by Mystery Writers of America). I became involved in MWA, met a lot of other writers, and really liked the writing world, and said to myself, “Okay, what else can I do?”

So, I called Bob Weil. “Bob, great news! I decided my next book will be Dracula,” and he said, “Oh!” Then I thought, “maybe I’m not the kind of writer who calls his publisher and tells him what his next book is. Maybe I actually have to ask permission.”

In the non-fiction world that’s what happens. You make a proposal. You try to sell it to a publisher. They say yes. They give you some money, then you go write the book. So, Bob said to me, “Gee, I think you’re great, Les. I think you could do a wonderful job, but the marketing department was wondering what do you know about vampires? Would you consider working with a co-writer?”

I didn’t like that idea, but after it bounced around with the corporate decision-makers, eventually Bob came back to me and wanted Dracula and was glad I didn’t sell the project to a competitor. I love the Victorian period. To me, it’s just a fascinating time, because it’s the time when so many things that we think of as twentieth century movements began: Women’s rights, changes for people of color, the Industrial Revolution, and the end of colonialism. All those things started in the late nineteenth century. That’s sort of the long story of how I got there, but my next book is about the 1920s.

And that’s Lovecraft, right?

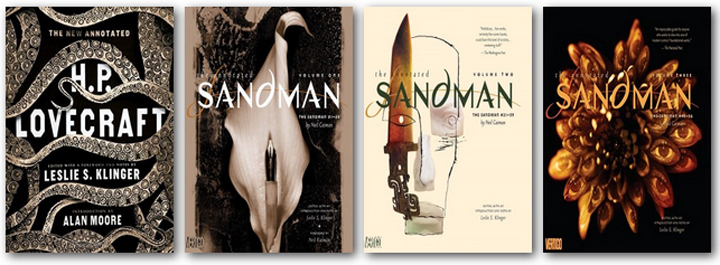

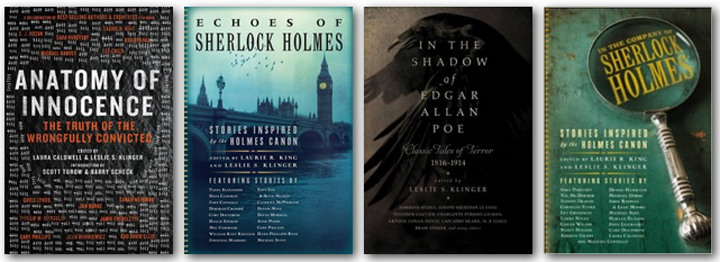

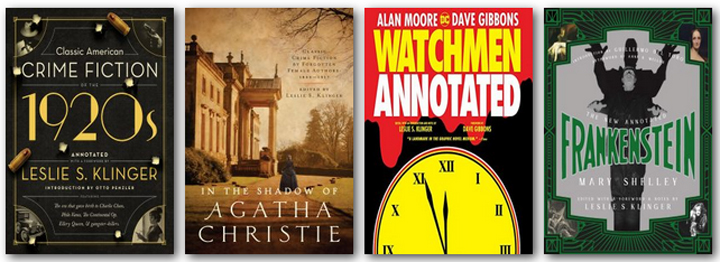

Well, yes, Lovecraft wrote in the 1920’s, and I did an annotated collection of Lovecraft, and there’s a second one of Lovecraft coming out, but I also started another series for Pegasus, and the first volume will come out later this year. It’s called Classic American Crime Fiction, and the first volume starts with the 1920s. This includes the first Ellery Queen, the first Charlie Chan, the first Philo Vance, Hammett’s Red Harvest, and the novel, Little Caesar all in one volume with a long scholarly introduction about how did we get to the 1920s in American mystery writing. I’m hoping the book will do well enough to turn into a series with the next volume covering the 1930s.

Now, I noticed you’ve done some Sherlock pastiches. Have you played around with any other fiction, or do you just love the non-fiction stuff?

I’ve written two short stories, and that’s it. I think like most writers I have a bad novel sitting on my computer. I felt like I really wanted to try my hand at it. It’s basically a science fiction novel, and it was a fascinating experience because it was so hard. First thing I did was call a friend of mine who was a novelist and asked if I had to outline. Then she asked me, “Can you tell me the story in three sentences?” I said, “Yeah.” She said, “Go for it. You don’t need an outline.”

But you sit down staring at a blank screen and wonder what are you going to tell me next. Part of it is simply that it’s a very different sort of time commitment to write a novel. For me, when you’re in the middle of a story you want to sit in front of the computer and get it out. You’ve got it in your head what is happening next, and you want to tell it, and that takes large blocks of time. The kind of writing that I normally do… it’s hard to explain, but I break it up into one hour or two hours…

I was curious, since you’re a lawyer, you’d think by the end of the day your brain would be so overloaded, but here you get into such detailed work with the annotations. Do you ever turn your brain off?

The short answer is I don’t ever turn my brain off except when I actually do fall asleep, and then it’s busy dreaming. I’m attention craving. There must be some kind of disorder there. I like to have my mind busy, whether it’s playing a game or whatever. But it’s really easy to do this kind of writing in short blocks. It’s easy to go home, cook dinner and go upstairs to write for an hour. Then if I’m really into it and my wife is very kind, the entire weekend I’ll spend up in my office writing. I can do a typical footnote in a half hour but it varies and can be up to two hours. So, the writing process breaks up into little pieces. Whereas in fiction writing it wasn’t comfortable breaking it up into little segments like that. Someday, I’d like to get back to the novel, and see if I can make it better. I have so many other projects in mind. Maybe if I took off for three months or something.

You said you were originally drawn to science fiction when you were a child. Who inspired you?

Oh… all of them. I was an omnivorous reader. Not so much fantasy. I didn’t discover Tolkien until college. In the Sixties, there was this sudden discovery of Tolkien. Every college dorm room had a “Welcome to Middle Earth” poster. After that, people were naming their children with Elvish names. That’s when I discovered Tolkien. Before that, however, I’d been reading Heinlein and Asimov, Poul Anderson, A.E. van Vogt — everybody.

No, I didn’t read Lovecraft. That was an embarrassment in a way. The idea to do the Annotated Lovecraft, I must say, came from Bob Weil, not from me. So, the process, as I said, was not an easy one. You pitch the publisher on a book. Then they tell you yes or no. So, after I finished Dracula, it was obvious to me that the next project should be Frankenstein, but W.W. Norton & Company said, “No.” They said the book didn’t sell well, steadily, but not volumes, and they didn’t think there was a particular market for it. This was in 2008. So, I went back to them and pitched another half dozen ideas.

The Sherlock volumes came out in 2005. I obviously had written a lot of essays, but I was done with those books. Some of the other great ideas I had: War of the Worlds, The Lodger… I always wanted to do a book about the Ripper. Marie Belloc Lowndes wrote a wonderful book called The Lodger, which Hitchcock adapted into a film. I can’t even think of all the books I’ve pitched, and I was told, “No.”

Then Bob said to me, “What about Lovecraft?” The reason why he liked it was because he thought there was a built-in audience. He was right about that one. I had always heard about Lovecraft and knew he had been a major influence on a lot of writers, but I had never read his stuff.

It’s good story material.

I agree. It’s really good. Then, to my delight, the Annotated Lovecraft volume did very, very well, and Bob said to me two years ago, I guess, is there enough material for a second volume? I said, “Yeah, we really had to trim and cut it down to 22 stories on the first volume, and some of the cuts were painful.” So, there will be a second volume that will come out in 2019, but Lovecraft was not one of the ones I read back in those days. To my delight, I found out the science fiction writers were all Sherlock Holmes fans.

Really? Such as?

Van Vogt, Poul Anderson, Isaac Asimov… Asimov, Anderson were members of BSI… I don’t think any of the others were members of the Irregulars, so early on… Phillip Jose Farmer was a long-time Sherlockian. He wasn’t a BSI but founded his own Sherlockian society in Peoria, IL, and you can see the influence from it in some of the stories that would have references to Holmes.

Can you name a specific story?

Van Vogt’s Slan has references. Poul Anderson wrote the “Case of the Missing Martian Crown Jewels” in which Sialock is a Martian detective and so on. Asimov wrote a whole series of short stories that are Sherlockian parodies. Early on, a friend of mine and I started a science fiction book club. This came about, because I recognized Harlan Ellison while riding in an elevator, and I realized he was going to see a lawyer on another floor that was a friend of ours. I called up the lawyer and asked if he could connect me to Harlan. Then I called Harlan and introduced myself saying that we were a group of lawyers that had formed a science fiction book club. We’d like to take him out to lunch or dinner to talk about his books. He said, “Let me get this straight. You’re lawyers. You’re going to pay for me? I’m there.”

So that was the beginning of our little club. The authors that were coming to town or lived nearby were thrilled that intelligent readers were going to pay for a nice meal. They weren’t squee-ing fans. Ellison was first. We did Van Vogt. We did Phil Farmer who happened to be in LA for something and came over my house for dinner. Also, Poul Anderson. It was almost coincidental that they’d find out I was also a Sherlock Holmes nut. That was a common thread for a lot of them. Larry Niven and I ended up meeting in a limousine sharing a car coming back from the airport.

By the way, this wasn’t planned, but just about everyone I interviewed for the past year or so for Black Gate had something to do with vampires. Of course, you did the Annotated Dracula. I also interviewed Nancy Holder who did the novelizations of Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Charlaine Harris with her Sookie Stackhouse series and Nancy Kilpatrick.

Charlaine and I met when we were on the MWA board. What happened was the Southern California chapter was in a state of disarray. I was on a board and the national vice president called me up and said, “We need you and one or two of the other board members to pull it together — recruit, find a new chapter president, etc. The other board members looked and me and said, “You have an office staff. Why don’t you be president?” So, I became chapter president for two and a half terms and being a chapter president meant being a member of the national board. So, I got to become friends with a lot of mystery writers from around the country. I had already been friends with all these Southern California writers. So, I got to meet Charlaine. A few years ago, I moderated a panel at Bouchercon on Supernatural Mysteries. I said to Charlaine, who was also on the panel, “You’ve announced that you’re done with the series. Tell us what’s next. What’s the next great trend that everyone’s going to want to write just like you?” She didn’t have a new trend to announce, or she wasn’t going to tell us.

I was really shocked over at Bouchercon as to how big the paranormal mystery market was. I keep on laughing, because I keep on running into her, and she will get her interview this year, but Heather Graham is a perfect example too, because she’s so cross genre.

Absolutely… and Toni Kelner. Toni writes with Charlaine from time to time. Back to the Sherlockian pastiche… you know that Laurie R. King and I have this anthology series going. The first one was called A Study in Sherlock. The second one was called In the Company of Sherlock Holmes. The third one is called The Echoes of Sherlock Holmes. The first two were published by Random House and the third by Pegasus. These are all stories inspired by the Sherlock Holmes Canon. One of the stories I wrote.

Basically, we went to friends and asked if they wanted to write a story. The idea came about, because I had always been tagged for panels on Sherlock Holmes even if I wanted to talk about Victorian crime or whatever, and Laurie, too. Laurie and I have been on a dozen Sherlock Holmes panels. This was at Left Coast Crime, and I asked the programming people if I could do something different from the normal Sherlock Holmes panel. Instead, I wanted Michael Connelly, Lee Child, and Jan Burke on the panel. They were all attending, and I knew they were all secretly fans of Sherlock Holmes. So, we did this panel, and it was great. Lee would say, “I don’t know much about Sherlock Holmes, but… and say something very perceptive, and the same thing with Michael and Jan. After that I mentioned to Laurie, “What if we ask them to write stories?”

Lee and Jan were in the first volume. Michael was too busy, but he was in the second volume. We had Neil Gaiman and other amazing A-list writers. The fourth volume comes out in October, and it’s called For the Sake of the Game. Toni’s got a story in it. We asked Charlaine but she didn’t feel comfortable that she knew enough about Sherlock Holmes, which is probably not true. But in any event, people write short stories for the joy of it. Nobody does it for the money.

By the way, I bought your Volume 3 of your Annotated Sherlock Holmes, and I also picked up a copy of one of the Wessex Press annotations on The Last Bow.

Only nine more [of the Reference Library volumes] to buy. You need the other two Norton volumes of Holmes as well, because if you put them on the bookshelf next to each other they finish the profile of Holmes on the spines. They all fit together beautifully!

Good to know. But getting back to my question, I read your interpretation of The Last Bow. Do you suggest reading the story first and then re-read it with the footnote annotations? Otherwise, you could go two pages at a time and go back and forth.

You read the story and go back with the notes. The reason why I suggest that is first of all the notes are not spoiler-free. They can’t be, because part of the purpose of notes is to point out some of the foreshadowing, and this against this. Once I saw that somebody was reviewing my New Annotated Frankenstein online, and they commented how there were two pages of notes about an asylum in Paris — the history about the greatest asylum in Paris, which is mentioned in three words in one sentence in the book, but it was so interesting.

When I read The Last Bow the other day, you mentioned something in your annotations about a foreign hand or something like that. I read the footnote and thought, “Gee, I never heard of that term.” And it was so funny, because I’ve read that section so many times, and it’s one of those things that I didn’t know what it meant, but it just kind of worked, and I didn’t question what it meant, because the story flowed.

My aim with footnotes is that it’s supposed to make the reading experience more pleasurable. It’s supposed be things that say, “I didn’t know that,” or you say, “That’s really cool.” This supposed to be fun. I love getting into things that are there but aren’t essential to the story. The books in the Reference Library, as you’ll see, are very different from the Norton volumes, which are the most illustrated versions of the Canon ever published. Secondly, the Norton notes are deliberately more about historical and cultural things than about Sherlockian theories. The Reference Library is much more Sherlockian in essence. Most of the notes in the Reference Library are a compendium of Sherlockian research as compared to writing a long note as to what’s a foreign hand or something like that. A wise friend of mine once said, “It begins with Sherlock Holmes, but it ends up being about friendships.” During BSI week, it’s such a treat. I meet up with dear friends that I get to see in-person once a year. We’re very close while we’re together, and then we don’t see each other for a while.

You’ve done the Annotated Sandman, and you’ve also done the Annotated Watchman. These graphic novel series are completely different from the other stuff you’ve done. How did you get involved with all that?

There was still a Sherlock Holmes element involved. I met Neil Gaiman through Mike Whelan, the current president of the Baker Street Irregulars. Mike invited Neil to come to the BSI dinner back in 2002 as a guest, because he knew he was interested in Sherlock Holmes. I think Michael Dirda, who was sort of our literary recruiter, had suggested him. Mike seated us together at the dinner. Don’t know why. Just thought we’d hit it off, and we did. We became friends. Actually, when I was doing Sherlock Holmes, I showed Neil some galleys, and he came up with some very good suggestions as to how to organize the book. He was very helpful. Then, he wrote the introduction to Dracula.

We were friends first, and then at some point along the way he said to me, “So, are you actually any good as a lawyer?” I said, “Yes, I’m actually very good.” So, he said, “Good, I need one.” I’m his lawyer now, too.

He had come to me with suggestions about books he thought would be good to annotate. His favorite idea, and one of my favorites, too, was to do Kim by Rudyard Kipling, which really needs annotation. The whole Indian culture is so interesting — the Raj, the grand game… but it doesn’t sell well. So, that idea didn’t go anywhere. But we always joked about doing Sandman, because I love the comics. They are very literate, but Neil said, “Let’s wait till I’m dead.”

Then one day, we’re talking, and he said to me, “I’m starting to forget some of the things that I wrote in Sandman. We should do this now. I’m calling DC Comics.”

He had enough clout there. He called DC and they said, “Yes, sir.” So, the next thing I know we were working together, and he was wonderful. He had all the original scripts.

For some reason, DC decided to spread out the publication project over three years. When the last book finally came out in 2014, I guess, I was out having lunch with my editor at DC, and in passing I told him that my dream project was to do Watchman, another truly literate graphic novel. So, he said, “Make us a proposal.” So, I wrote up a two-pager figuring it wasn’t going to go anywhere and sent it in. Four or five months later, I asked him where my author copies for the last volume of Sandman were, and that’s when he told me they were moving ahead with Watchman. Then I asked, “With me?” and he said, “Yeah.”

Leslie Klinger giving a speech at Sherlockian dinner at Bouchercon 2017 in Toronto.

Laurie R. King is seated behind him to his left.

Did you need permission?

Oh yes, but my editor said, “Don’t start, yet.” So, six months later, he finally got back to me and said, “Okay, the corporate people up at the top have now approved you on the project. Let’s get going, and we’d like it in six months.”

So, he put me in touch with its illustrator, Dave Gibbons. Alan Moore wanted nothing to do with the project. This wasn’t anything personal. He’d already written the introduction to my Annotated Lovecraft, and I think we already had a good relationship — A quick story how that came about—when I was touring in England and was meeting with the Count Dracula Society based in London for the Dracula book, I met Leah Moore, Alan’s daughter, and her husband. She and her husband were doing a comic book called the Complete Dracula, a beautiful graphic novel. We had a Sherlock Holmes connection, too. They asked me if I would help them with it and just read it over. I agreed. So anyway, we got to be friends, and I also helped them with a couple of Sherlockian graphic novels.

Then, I emailed Leah and said, “How do I best present to your dad that I’d like him to write the introduction for my Annotated Lovecraft?” She emailed me back eight hours later and said he’d love to do it. I said, “Leah, I didn’t want you to ask him, I just wanted to know how to go about it.”

So anyway, he was onboard with that, but he did not want to be involved with Watchman, because he said it’s really a closed chapter of his life. He doesn’t want anything to do with DC any more. What happened, I think, was when he and Dave Gibbons wrote Watchman they had no idea of the success was going to be and how tightly DC would hold on to it.

When was Watchmen written?

In ’86. The deal was they’d get the copyrights back when the book went out of print, but it never went out of print. DC has controlled the rights for all those years, and did things like the movie, and the Before Watchman series, and I think Alan hated all of that. I think he felt that they were exploiting his characters and ideas without his involvement or permission. So basically, he said, “this is a closed chapter of my life, and I don’t want to go there.” Alan has moved on. Dave Gibbons, on the other hand was eager to help with the annotations and had actually been involved in some other books that had been out in the past twenty-three years and had talked at length about Watchman. He had a copy of all the scripts, which was essential for me. He read every single note that I wrote and had comments and became very involved with the process. So, it was really a pleasure to do that book. But to me, it’s a murder mystery. “Who killed the Comedian?” is really the subtitle of the book.

It’s also an alternate universe.

It’s a combination of everything I love. I can’t think of another graphic novel that would intrigue me like those two did. I’d like to add that Neil and I and his publisher have shaken hands on doing an annotated edition of another of his major works, but the deal is not signed yet, so I can’t say any more at this point.

So, did we go over all your questions? I do ramble on. You can tell I like to tell stories.

Crowens (looking over notes): You’re going to laugh. I have a note here to myself that Sherlock’s logic would be contradictory to your interest in Gothic horror such as in Dracula and Frankenstein, and yet you love both, and I wrote down the quote from The Sussex Vampire that “This agency stands flat-footed upon the ground, and there it must remain. The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply.”

There’s been a tremendous amount of crossover. First, there’s been at least a dozen or more Sherlock Holmes versus Dracula stories… Sherlock Holmes on the same side as Dracula, and I just love all those things in that tradition.

I was curious because Black Gate is an action/fantasy magazine, but what was it like interviewing George R.R. Martin at Stokercon 2016 on the Queen Mary in Long Beach, California?

He was just a treat to talk to. I met him before through Neil, and again, we just had a lot of common interests. He’s done science fiction stuff. He’s done vampire fiction. Obviously, he’s done the whole sword and sorcery thing, which is my secret passion — not reading so much but in role playing games. My primary recreational activity over the past thirty years has been… starting with Wizardry … has been computer role playing games — mainly the sword and sorcery kind.

Am I allowed to mention that?

Certainly. I’m sad to say I’ve put in more than two hundred hours each on Elder Scrolls Online, Skyrim, and Dragon Age Inquisition. I love those kinds of games.

Do you ever sleep?

Not if I can help it. Some people think I’m a vampire. I still remember very early on I had dinner one night with Boris Bitker, a name that probably doesn’t mean anything to you… now a retired professor at Harvard. He was, at that time, the most eminent tax professor in the world. I said to his wife, “Does Boris love science fiction, or mysteries, or puzzles like I do, because I assume that’s what makes a great tax lawyer?” She said, “No, he only reads tax material. That’s all he ever reads.”

Creatures of the mind… I didn’t wake up as a kid and say I wanted to be a tax lawyer. I stumbled there, but it all makes sense to me looking back at it now. Tax law is like nuclear physics. It’s very abstract. There’s a lot of game playing in your head moving pieces around and all that. So, it all does fit with Sherlock. Somebody once said to me, “Ah ha! Deduction!”

… as in tax deduction.

Leslie S. Klinger was the technical advisor for Warner Bros. on the film Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011) and served (without credit) in that role for Warner Bros.’ earlier hit Sherlock Holmes (2009). Klinger also lectures extensively on Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, Arthur Conan Doyle, Dracula, Bram Stoker, H. P. Lovecraft, Frankenstein and the Victorian age. He has taught a number of courses on these topics for UCLA Extension. Klinger has travelled extensively as a public speaker on these topics, including programs in Istanbul, Transylvania, Toronto, and the House of Lords in London, as well as college campuses around the U.S. www.lesliesklinger.com

Elizabeth Crowens is a Hollywood veteran, journalist, and author of Silent Meridian, a 19th century X Files / alternate history novel series. It won First Prize in the 2018 Independent Press Awards in Steampunk, First Prize in the 2016 Chanticleer Review’s Goethe Awards for Turn of the Century Historical Fiction and was short-listed as a finalist for their 2016 Cygnus Awards in Speculative Fiction, Paranormal and Ozma Fantasy Awards and a finalist in the 2017 Eric Hoffer Awards. www.elizabethcrowens.com, Facebook: @BooksbyElizabethCrowens, Twitter: @ECrowens

A fascinating, wide-ranging interview with a fascinating, wide-ranging subject. Brava!

And totally worth it for the last-line pun, “Deduction!” [grin]