Short Fiction Reviews: Paradox and Interzone 210

A Look at Current Sci-fi and Fantasy Magazines

By David Soyka

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

Paradox describes itself as “The Magazine of Historical and Speculative Fiction”; the most current issue of Winter 2006-2007 (due to a change in bi-annual publishing schedule, the next issue won’t appear until October 2007), favors primarily alternative history. Sarah Monette’s “Amanta Dorée” posits a prostitute/spy with a secret in a nineteenth-century New Orleans where France maintains ownership of the Louisiana territory. “After the Circus” by Danny Adams imagines what, had he survived, hero of the Fatherland Manfred von Richthofen-more famously known as the Red Baron flying ace of World War I and Snoopy fame-would have made of Adolf Hitler. “Somewhere, Sometime in the Nile” by Stephanie Dray ponders alternate histories for Israel and Palestine as affected by a disenchanted time traveler whose bereavement over the loss of her son changes history to something more like what we know it.

Paradox describes itself as “The Magazine of Historical and Speculative Fiction”; the most current issue of Winter 2006-2007 (due to a change in bi-annual publishing schedule, the next issue won’t appear until October 2007), favors primarily alternative history. Sarah Monette’s “Amanta Dorée” posits a prostitute/spy with a secret in a nineteenth-century New Orleans where France maintains ownership of the Louisiana territory. “After the Circus” by Danny Adams imagines what, had he survived, hero of the Fatherland Manfred von Richthofen-more famously known as the Red Baron flying ace of World War I and Snoopy fame-would have made of Adolf Hitler. “Somewhere, Sometime in the Nile” by Stephanie Dray ponders alternate histories for Israel and Palestine as affected by a disenchanted time traveler whose bereavement over the loss of her son changes history to something more like what we know it.

Alternate history is about “what if,” but it also needs to think about the “why” of the “what if.” Otherwise, it’s the same kind of situation as in fantasy-okay, you’ve got elves and heroes and quests, but what’s the point? If you just want escapism, well, okay, if you like that sort of thing (and, yeah, I know how much certain folks hate that sort of phrase). So, okay, the South won the Civil War, or JFK wasn’t assassinated, or Napoleon was taller, or George W. Bush really did lose Florida (if only). But, what’s the point?

Philip K. Dick created alternate realities as a way to question the one we actually live in. The vast Harry Turtledove alternate history opus (of which I am familiar of only a small fraction, so I’m speculating a bit here) seems to suggest that even if things had been different, they may still have turned out more or less the same because, well, that’s the way humanity is.

Of more recent vintage are the alternate World War II novels of Jo Walton’s Farthing and Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America. Walton deftly shows how the tendency of otherwise decent people to “just go along” makes evil possible, while Roth, not surprisingly, portrays a more blatant American anti-Semitism.

In his novels, The Light Ages and House of Storms, Ian R. MacLeod ponders the social upheavals wrought by technological change in an Industrial Age where magic combines with machinery. MacLeod’s novella, “The Master’s Miller Tale” (May 2007 Fantasy and Science Fiction) takes place in the same alternate universe. The protagonist is the titular last of the master millers, vainly trying to compete against the new steam-powered mill. The miller joins a group of Luddites who resort to terrorism to halt progress, with disastrous consequences. The story poignantly conveys the doomed struggle to preserve what you love in the face of uncontrollable forces.

In contrast, most of the stories in Paradox lose me because they focus on the “what if” with little consideration of “why.” Take, for example, Monette’s tale, which is probably the most intriguing in terms of setting and characters. There’s a murder, though it’s not one of those “figure out the puzzle” kind of murder mysteries, and the central character’s ambiguous identity, which isn’t hard to figure out. Overarching this is an English spy to whom the prostitute is attracted, and he may perhaps reciprocate, but they are fated to stay apart, and not because they work for different governments. All of this reads as if it’s a setup for a series, or the opening chapter of a novel, but as a self-contained story, I’m struggling to figure out the “why.” Why should I care about the protagonist’s situation, what difference would it make if it took place in an historically accurate New Orleans rather than an invented one, what is the point of the character’s sexual behavior, beyond the tired old symbolism of how we all prostitute ourselves for some seemingly better cause?

I don’t know, anymore than I know why some stories have wizards in them. Just because they can doesn’t seem sufficient.

One story in the subgenre I did like was “The Qualities of a Monarch” by C. Kevin Barrett, which won the magazine’s “flash alternate history” contest. Two men are attending an execution involving King Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn. This being alternate history land, you can guess the subject of the beheading in this version might affect Charles Laughton’s career. The reason for the execution is a humorous inversion of the real Henry’s political justifications for his multiple bad-ending marriages.

The remaining stories are either straight historical fiction, “The Luck of the Irish” by Brian K. Crawford, or hybrids with fantasy, “The Duke of Bedford Prays for His Brother’s Soul” by Anne Sheldon, or science fiction, “Marathon” by Bruce Durham. The latter is a time traveler ostensibly observing the famous Greek battle that provided the length for modern-day long-distance running races. The protagonist must take on the role of the first Marathon runner and also figure out some way to avoid his fate. There’s an amusing line when the character announces his arrival, but other than that, nothing that makes me want to go the distance.

Sheldon depicts the brutality of medieval times, something that gets lost in today’s Renaissance Faires, in considering moral questions that, alas, have not been banished to the dust bins of history. How can people pillage and rape and claim their actions fulfill a higher good? How might they suffer for it, and to what extent might they be aware of the suffering they’ve caused? What price are they willing to pay?

Finally, the “Luck of the Irish” is a colorful pirate story, even while you can guess that when a trio of escaped convicts murder and impersonate the crew of a trading ship, they will soon come to regret assuming identities they don’t know enough about. Particularly nice is Crawford’s description of the baby-faced adolescent mid-shipman who eventually proves the downfall of the convicts’ ruse. However, an editor who allows a story to actually print the phrase a “chill went up his spine” should be made to walk the plank.

Interzone 210

Interzone 210

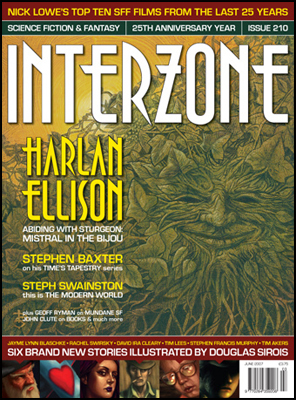

There are a couple of odd things about the June Interzone. The first is that the cover prominently displays the names of Harlan Ellison, Stephen Baxter, and Steph Swainston. I guess I can understand that this might be a way to attract interest. However, I think people buy the magazine primarily for the stories, and none of these three contribute fiction; Baxter and Swainston are the subjects of interviews, while the Ellison is basically his introduction to an upcoming collection of Theodore Sturgeon stories…as you might expect, the article is as much about Ellison as Sturgeon, though certainly worth checking out if you’re interested in either of these guys.

All of the fiction is illustrated by Douglas Sirois, which leads me to the other odd thing. Not that you’d have a single illustrator, but why an illustrator would, for Jayme Lynn Blaschke’s high adventure tale, “The Final Voyage of La Riaza,” draw a character with a full white beard when the author describes the character’s beard as “sparse”?

After you blow through the opening pirates flying through the air with not exactly the greatest of ease, things get considerably more serious and darker. The standout here is “Heartstrung” by Rachel Swirsky, which takes the phrase “heart on your sleeve” to literal extremes. In this Angela Carter kind of fantasy, a mother sews her coming-of-age daughter’s heart onto a sweater, just as her own mother had done for her. But the mother pricks her finger during the process, and as a result begins to have feelings she hasn’t had since her own heart got sewn on a sleeve. Which makes the mother wonder if what she had just done for the daughter really is for her own good.

“Tearing Down Tuesday” by Steven Francis Murphy, is a parable about child abuse. In some kind of post-apocalypse, Kyle’s favorite robot is about to be dismantled. Problem is, Kyle feels more affection for the robot than most people. Further complicating matters is that the robot is suicidal. Along comes the Reverend Robinson with an idea of how Kyle can earn money to buy the robot before it is turned into parts. How Kyle and the robot gain their freedom, and at what costs, demonstrate how a “non-real” setting provides emotionally resonating truths about what happens in real life.

A similar post apocalyptic world is the setting for “Preachers” by Tim Lee. The narrator’s father was a mechanic who openly disdained the paramilitary authorities. When fuel becomes scarce, so do the machines that rely on them. Farming becomes more difficult. The world changes. A group of traveling preachers attempt to provide an explanation for the dire straits of the world. Some things never change, however, such as the choices a son makes in a world no longer like his father’s.

“Dr. Abernathy’s Dream Theater” by David Ira Cleary is another example of Victorian steampunk that seems popular of late. The narrator is addicted to a substance called “kuuf,” without which he becomes dimwitted. Echoes of Poe, here, in which the narrator engages in a “scientific” experiment to determine the nature of dreams. And which are worse, the ones generated from our subconscious, or from our pharmaceuticals?

Really creepy is “Toke” by Tim Akers in which a group of boys terrorize a race of scarecrows. Except that it’s the scarecrows who will terrorize them as the narrator personally learns how the scarecrows came to be.

I don’t know how much we can learn from history, even history that didn’t happen, but the horror here provides useful reminders about why history is the way it is, in whatever version.