Short Fiction Reviews: Greatest Uncommon Denominator, Darker Matter

A Look at Current Sci-fi and Fantasy Magazines

By David Soyka

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

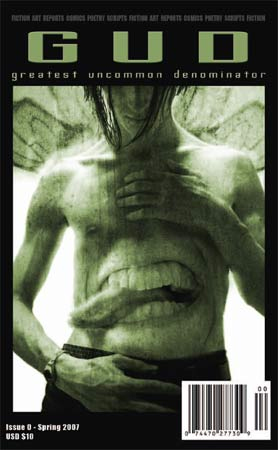

Greatest Uncommon Denominator is a new biannual that features decidedly strange stories, poetry, essays and artwork. The Spring 2007 debut, identified in an apparent attempt to be clever as Issue #0, has a cover page with the torso of a young boy whose stomach has a very large mouth with a lolling tongue. Gives you some idea of its savory contents.

Greatest Uncommon Denominator is a new biannual that features decidedly strange stories, poetry, essays and artwork. The Spring 2007 debut, identified in an apparent attempt to be clever as Issue #0, has a cover page with the torso of a young boy whose stomach has a very large mouth with a lolling tongue. Gives you some idea of its savory contents.

There are a few recognizable names, at least to me — Jason Stoddard, Bruce Boston, Charlie Anders (whose “Cutting a Figure” is an hilarious parable of breast implants that transmit Internet spam, highly recommended) — and a few that may someday become more so. Debbie Moorehouse leads off with the ironically titled “Sundown,” which takes place in an England following some kind of environmental disaster. The narrator is a “tracer,” a mercenary hired to track down runaway kids. Yes, we’re in Philip Marlowe territory, complete with the woman who comes desperate pleading for help to the seedy office of the private dick struggling with the possibility of a conscience. Moorehouse nicely subverts this well-worn trope with a meditation on hope in the face of hopelessness that contrasts the narrator’s affectless efforts to revive a fallen sparrow to his emotions regarding a dying ex-partner and the consequences that befall those he rescues.

There are a number of shorter works, such as Michelle Garrne Flye’s “A Yellow Sun with a Purple Crayon,” three paragraphs in which the narrator is asked to, you guessed it, draw a yellow sun with a purple crayon. Its brevity is preferable to “A Problem with the Law,” a poem by Neil Davies. I lost patience with this long before it finally got to the point. The repetition might be intended to represent the pervasive unfairness over which we have little or no control, if only because we are overwhelmed by all of it. Still, I found myself skipping ahead.

A. B. Goelman strings together four humorous vignettes in “4 Short Parables Revolving Around the Theme of Travel,” the best of which is a retelling of the scorpion and the frog folk tale. In this version, the scorpion has a French accent and publishes in Foreign Policy, but still is a slave to his nature. The disturbing part is how accurately it reflects international politics.

Other highlights include “Where Water Fails” by Rusty Barnes. While most of the fiction here is rooted in genre, this is one of two more or less realistic “literary” narratives. If anything, it might be called a horror story, but in this case the horror is that of the uncertainties of middle-life and growing old with someone you thought you knew, and realize that in some sense you still do. A darker-much darker, and all the more creepier in that it rings true-version of a mid-life crisis is offered by David Bulley in “Longs to Run.” Along the same lines, though funnier in a sick kind of way, is “Sown Seeds” by Errid Farland — if you have to die, there are worse ways of doing it, even if it does leave a bit of a mess behind for those who tried to help you out, and even if significant others may not see it that way. “Chicken,” by John Mantooth, is, like “Where Water Falls,” all the more horrific because of its realism, in which a young punk learns what happens when a bluff is called, which leads to a troubled kind of happy outcome.

One of the centerpiece stories is “Songs of the Dead” by Sarah Singleton and Chris Butler. They imagine (at least I don’t think there’s any history of such an event) that before his apprenticeship to engraver James Brasire, a young William Blake contracted to do a portrait of mental patient. Her doctor, Charles Bishop (note the irony of the last name) believes the need to sit still for a portrait has therapeutic value. Unless, of course, the patient is truly possessed by demons, even though the emerging “profession” of psychiatric care would discount it. Worth the price of the issue, as they say, with unexpected plot twists in which people, possessed or otherwise, are not always what they may seem.

While GUD appears in both print and PDF versions, Darker Matter is strictly a webzine, focusing on science fiction. Also new, the venture is published and edited by Ben Coppin. While it is freely available, the site and its authors are supported through donations and advertising.

While GUD appears in both print and PDF versions, Darker Matter is strictly a webzine, focusing on science fiction. Also new, the venture is published and edited by Ben Coppin. While it is freely available, the site and its authors are supported through donations and advertising.

Issue #3 features the last installment of a previously unpublished interview with Douglas Adams, based on “recently discovered” tapes of a conversation conducted with freelance journalist Ian Shircore in 1979. In the Analog tradition, there’s also a “science fact” article, I. E. Lester’s speculations about alien life forms. There are also five short stories, which can be rated by readers on a scale of 1 to 10, though I’m not sure that this is a particularly useful feature just because the technology allows it. Do you skip a story because some previous reader(s) gave it less than a five? Although, I guess the other side of that argument is, do you skip a story because some reviewer didn’t like it? The difference, I think, is that if the reviewer over time seems to have similar tastes to yours, then that might serve as some sort of reasonable benchmark, as opposed to an unknown collective, or just one person, who might have the critical faculties of, say, Harriet Klausner, the mythological Amazon reviewer famous for invariably gushing with gusto without distinction.

The lead story is “The Connection” by Bud Sparhawk and Ramona Wheeler (okay, if you’re really curious, it’s rated as seven stars, though all of these ratings could have easily changed with additional reader evaluations by the time you read this). As you might guess, it’s about the modern-day phenomenon of the need to be connected, playing on the slang of “connection” for a drug supplier as well as the electronic connection to cyberspace. It is perhaps all the more ironical that a story satirizing the need to get connected, even if it is for the less pleasurable experience of work, appears on-line, it doesn’t rise above vignette status in something that’s pretty much obvious, though redeemed by a slight twist at the end. (My rating: five stars.)

Eugie Foster ponders “The End of the Universe” (eight stars). For some reason, every thirty two thousand years, there’s a rift in the celestial underpinnings and the universe is disrupted. A group of software and sorcery experts headed by a recovered drug addict band together to get the universe over the hump. The trouble is, their readouts seem to indicate they should just let God — and everyone has a slightly different vision of who God might be — take over. The ending is a little abrupt, and a bit too pat, after a long set up, but overall I’d tend to go more or less with the reader rating on this one.

“Raft” by Larry Tritten (six stars) seems to be saying something about an uncaring universe. A spaceship explodes, ejecting a cube containing a man and a companion beast. Things don’t turn out well for the survivors, but the universe continues. Tritten says the story “was inspired by a short story by Evan S. Connell Jr. titled The Yellow Raft about a pilot shot down in the South Pacific during WW II.” (My rating: four stars.)

“Severance Pay” by Shane Nelson (eight stars) takes place in a totalitarian society. The protagonist has lost his wife and children because, he believes, of the bureaucratic ineptitude of a government to which he was once unquestioningly loyal. He loses his job and must resort to drastic measures for income. The metaphor here is about what we lose by chance and what we choose to lose when we have nothing left to lose. Choice, then, simply becomes an illusion in which we can only submit to the inevitable. I’m not sure the philosophical discussion is that closely tied to the denouement, but the irony of the title certainly packs a wallop when you do finally get there. While the shorter stories might have benefited for a little more development, I thought this one was longer than it could have been; still, I’d go along with the reader rating.

“Zinzi-zinzi-zinzic” is the sole bit of language used by an alien culture to proclaim victory after subtly conquering other species by way of their shadows. Until, that is, some one else, or some thing else, absorbs them, and that one word becomes a warning cry that no one else can hear. Robert Jeschonek gets seven stars by readers, and that seems about in the general neighborhood of where I’d put it.

Overall, not a bad collection of stories. The design, however, looks like something from 1997 rather than 2007. Three stars.