Short Fiction Reviews: Fantasy Magazine, Realms of Fantasy, and Heliotrope

by David Soyka

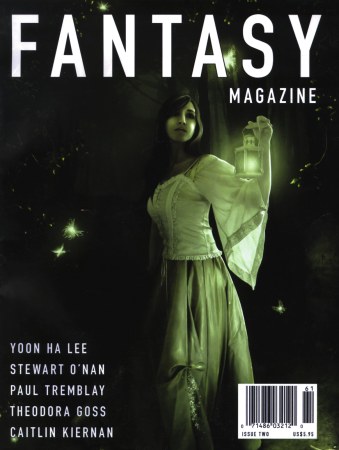

Fantasy Magazine, Issue 2 [Prime Books, edited by Sean Wallace, $5.95]

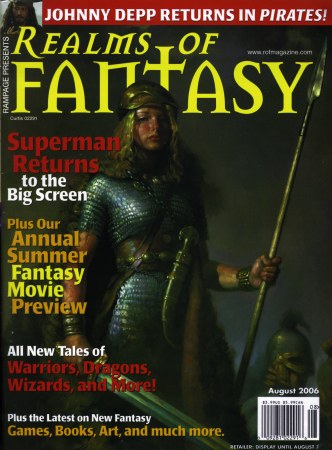

Realms of Fantasy, August 2006 [Sovereign Media, edited by Shawna McCarthy, $3.99]

Heliotrope, August 2006 [Fantasy Book Spot, www.heliotropemag.com]

In an August 4, 2006 blog post, Charles Stross remarks that,

Fantasy is, almost by definition, consolatory and escapist literature. Pure fantasy doesn’t really tell us anything about the world we live in…

Of course, that depends on how you define “fantasy,” pure or otherwise, which, as with “science fiction,” comes with the pejorative baggage not only of mindless escapism, but of badly written escapism. Stross seems to mean by “pure fantasy” the Lord of the Rings formulaic horde, though it’s hard to be sure. (It is also a mite odd that a writer of a continuing fantasy series would make the same kind of Swiss cheese-holed generalization that raises hackles when made by figures outside the genre — see, for example, Sven Bickerts.)

Stross does make the one exception for Paul Park, and while admittedly he’s talking about current publishing trends, such a simplistic observation ignores such folks as China Mieville or Kelly Link or Jeff VanderMeer, to name just a few of the top of my head, not to mention, say, Kafka or Shakespeare, all of whom have quite a lot to say about the world we live in.

Putting aside the literary merits of the form, “fantasy” is a marketing classification — people who intentionally browse the fantasy section of the bookstore have certain expectations about the goods on display. When you go to a pizza parlor, you expect something with tomato and cheese on a baked crust. Even so, there’s a big difference between what you get at Pizza Hut and what you get at a family-owned Italian eatery with a brick oven that only uses local produce and a sauce recipe handed down for generations.

In this respect, two magazines that contain “fantasy” in their titles may seem to be offering Pizza Hut fare, but actually contain something tastier (though, if what you crave is just Pizza Hut, you may be disappointed). One, Fantasy Magazine is a newly launched quarterly (which has had some initial growing pains in fulfilling subscriptions, but which seems to have been corrected) published by Prime Books, an imprint of Wildside Press, and edited by Sean Wallace. The issues I’ve seen feature on the cover wistful looking young women gazing at something presumably magical, leading you to think the contents concern themselves with faery land kind of stuff. But not quite.

The other is Realms of Fantasy, a much slicker, more established bimonthly production whose August issue displays a blonde woman outfitted in medieval combat gear with the subhead of “Warriors, Dragons, Wizards and More!” Again, you can’t always tell a book by its cover.

Fantasy #2 is a simple production — saddle-stitched, printed on inexpensive paper with black and white interior artwork that adds little or nothing to the presentation. There’s no editorial commentary or letters to the editor; though there is a book reviews department. The no-frills focus is on fiction, and even the interviews by Matthew Cheney are set ups for what might be considered (though there’s no overt indication that it is) the featured story. In issue 2, that honor goes to Theodora Goss, which already tells us to expect a fantasyland that’s more than mere escapism. Indeed, Cheney conducts a nice interview that rises above the mundane “where do you get your ideas” kind of questioning; in response to “Why are myths. legends, folktales and fairy tales relevant to the contemporary world,” it is interesting to note how Goss differs from Stross:

There are several ways in which fantasy is relevant to our modern world. The first is that the world is fantastical…our stock market operates on the Tinkerbell principle: it exists only so long as we believe in it. Imagine a roomful of brokers clapping their hands and saying, “I believe in Microsoft!” Our world is permeated by the fantastic. That’s why fantasy has become so popular, I think. Not because it offers an escape from the world, but because it expresses something fundamental about it.

Goss’s contribution towards this fundamental expression is “Lessons with Miss Gray,” a recurring character in her short fiction whose ostensible lessons in witchcraft are more deeply rooted in the wonder and loss of childhood innocence. Similar themes are sounded in Margaret Ronald’s “Sparking Anger” and Bruce McAllister’s “Ragazzo.” The former is darker — a young girl whose retribution against a predator ironically brands her as social misfit — while the latter is a riff on the idea of the “evil eye,” which in this case results in a positive transformation.

From a different perspective, Lavie Tidhar’s spookily moody “Children of the Revolution” ponders some coming of age stories that end before adulthood, a mediation on post-Soviet Russia and the perils of rapid industrialization. I wish there were a point to the whole story, a happy or meaningful ending with a sound moral truth, but things don’t happen this way. A good example of what Goss means by fantasy that expresses realism.

Another good example, and my personal favorite of this issue, is “Cotton Country,” in which Aaron Schutz depicts both the literal and figurative hellish legacy of slavery, while also pondering how those who genuinely intend to do good are no more rewarded in this world or the next. This story could just as easily have appeared in a literary magazine, in what would be accepted there as Toni Morrison-styled magic realism. As would Stewart O’Nan’s “The Novel of the Holocaust.” The title refers to an author on the verge of a book tour to publicize a fantastical re-telling of his life as a boy in the concentration camps. As an Oprah’s pick, widespread success seems imminent. Reality, however, is not better than fantasy, except for one outcome that makes a significant difference, as reflected in the brilliant last line.

That these stories would not be out-of-place in a non-genre publication is not meant to disparage their compatriots in these pages. It does serve to underline that fantasy can be serious stuff. Indeed, if there could be one criticism of this particular issue, it’s the lack of humor (though there are some chuckles in “Lessons with Miss Gray”).

More true to the form, perhaps, are the folktale-like “Nine Tails Hundred Hearts” by Yoon Ha Lee and “The Voices of the Snakes” by Karina Sumner-Smith. “On the Bus” by Patricia Russo concerns a dying woman who, in humoring a demented sister, takes an expected ride. Caitlin Kiernan gets best title award with “Madonna Littoralis,” a fabulist fish story that is best described in the author’s own words as, “about denying the immutability of form and affirming the fluidity of existence.” Paul G. Tremblay’s “It’s Against the Law to Feed the Ducks” is an end-of-the-world (at least as we know it) tale; though I’m not quite sure what to make of “Light of the Moon” by Karen Anne Mitchell, in which the narrator may be suffering because of her illness or because of her treatment. I suspect that is the point.

None of these stories strike me as mere “escapism” (though, by the way, what’s wrong with a little escapism now and then?). Nor do those in Realms of Fantasy (though the “realms” here do include a range of media, including reviews of movies and games that qualify as escapist). On the nonfiction side, the Folkroots column by Midori Snyder provides an interesting analysis of the disturbing details behind the myth of the armless maiden, a metaphor of a girl’s right of passage into adulthood that also features elements of parental and societal abuse, as you might expect when a woman’s brother or father hacks off her limbs. As Snyder points out, the “shocking metaphor of mutilation… erupted with savage reality” during the Sierra Leone civil war when rebels made a practice of hacking the limbs of women and children.

None of these stories strike me as mere “escapism” (though, by the way, what’s wrong with a little escapism now and then?). Nor do those in Realms of Fantasy (though the “realms” here do include a range of media, including reviews of movies and games that qualify as escapist). On the nonfiction side, the Folkroots column by Midori Snyder provides an interesting analysis of the disturbing details behind the myth of the armless maiden, a metaphor of a girl’s right of passage into adulthood that also features elements of parental and societal abuse, as you might expect when a woman’s brother or father hacks off her limbs. As Snyder points out, the “shocking metaphor of mutilation… erupted with savage reality” during the Sierra Leone civil war when rebels made a practice of hacking the limbs of women and children.

Other kinds of amputations are emotional or psychological in nature, as Scott William Carter’s “The Grand Mal Reaper” illustrates. The narrator experiences fits that transport him to somebody’s death bed; he cannot help the person in any way, he can only witness the person’s pain. The ending is both funny and, to some philosophical inclinations, true. “Indigo with Distance” by E. Catherine Tobler is the amputation of a loving relationship by cultural forces, and how, even after seeing irreversible tragedy, it endures in some form.

“Of Metal Men and Scarlet Thread and Dancing with the Sunrise” by Ken Scholes is in keeping with the cover art and the medieval warrior kinds of themes that Stross seems to disparage. The setting is a little more exotic, combining elements of steampunk, Lawrence of Arabia, and sword and sorcery. It contemplates the ethics and implications of the use of the ultimate weapon, though it sidesteps the question of why wiping out a civilization in one decisive devastating blow is any worse than the smaller-scale horrors of conventional warfare.

An oblique answer of sorts is provided in Darrell Schweitzer’s “The Hero,” which ponders the “collateral damage” caused by the mythical hero excised upon elevation to legendary status. And about which those who strive to emulate such heroic acts learn the truth of too late.

“The Cold Drake” by Renee Bennet is more pure mythology: a magical creature matures in human captivity to gain the strength to destroy her evil father and return home. Another coming of age riff is offered by K. D. Wentworth in “True North,” where children venture to a place where they can never fully return again, though the wiser ones will continue to find it in a different form.

Every one of these stories features a protagonist who in one way or another successfully escapes oppression, chooses not to escape as a means of opposing compression, or realizes that escape is not possible and achieves some peace in that realization (which is a form of escape). But there’s hardly anything escapist about any of that.

I’ve previously remarked on my own personal bias about reading fiction on the computer screen. Heliotrope, a new publication of Fantasy Book Spot, would seem to bridge print and pixel worlds by offering contents of the magazine in PDF format. Of course, you can print out web pages, too, but those pages are designed to fit on the screen, whereas these are pages designed for printout. It may be a minor distinction. If you actually want a print out version without using up your printer ink, you can order a copy that is “free,” though you pay $6.95 for shipping.

I’ve previously remarked on my own personal bias about reading fiction on the computer screen. Heliotrope, a new publication of Fantasy Book Spot, would seem to bridge print and pixel worlds by offering contents of the magazine in PDF format. Of course, you can print out web pages, too, but those pages are designed to fit on the screen, whereas these are pages designed for printout. It may be a minor distinction. If you actually want a print out version without using up your printer ink, you can order a copy that is “free,” though you pay $6.95 for shipping.

The premier August issue has a nice range of short fiction, articles, poetry and reviews. There’s also a comment feature, which is the unlimited “letters to the editor” function you’ll typically find on other magazine sites such as Strange Horizons. It also lets you download specific sections, or the entire magazine.

There are three stories. “Honey Mouth” by Samantha Henderson concerns how the unsolved murder of a child is revenged, thanks to an intermediary aware of the ghostly presence of the child and a swarm of bees. It is a conventional ghost story, though nicely written. “American Gothic” by Michael Colengelo, in contrast, is a horror story, which subverts the idea that the bestiality of humans makes animals appear to be superior creatures. According to Colengelo, it’s just a matter of perspective.

By far the wackiest story I’ve read recently is “On the Air” by Edward Morris. This is alternate history on speed in which the events of World War I end much differently, as this transcript of a show from the newly invented television illustrates in overwhelming detail. Some stories are jam-packed with adventure; this one is jam packed with historical and literary references. To just give you an idea, Hugo Gernsback is the show’s host. It’s not surprising the story is dedicated to Paul DiFilippo and also Lou Antonelli; Morris might have included Howard Waldrop, as well.

In keeping with our theme for this installment of reviewed fantasy short fiction, the editor of Heliotrope is one Jay Tomio, whose tagline in his posts to the comments sections is taken from M. John Harrison: “I think it’s undignified to read for the purposes of escape. After you grow up, you should start reading for other purposes.”

The aforementioned are as good a place to start as any.