Short Fiction Reviews: Fantasy and Science Fiction and Interzone

A Look at Current Sci-fi and Fantasy Magazines

By David Soyka

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

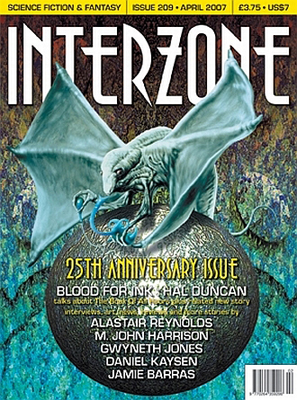

This installment of reviews is arriving a little late, so neither of our subjects this time around — September’s Fantasy and Science Fiction and the twentieth anniversary edition of Interzone — is likely still available at your local newsstand. Both venerable publications, however, sell back issues, so if anything here piques your interest, you should be able to get your hands on it.

This installment of reviews is arriving a little late, so neither of our subjects this time around — September’s Fantasy and Science Fiction and the twentieth anniversary edition of Interzone — is likely still available at your local newsstand. Both venerable publications, however, sell back issues, so if anything here piques your interest, you should be able to get your hands on it.

Indeed, if you’re intrigued by the less than overly prolific Ted Chiang and you’d like to check out his latest, “The Merchant and the Alchemist’s Gate” but can’t afford the collectible limited chapbook from Subterranean Press, then the September issue of Fantasy and Science Fiction fits your budget. Chiang’s fable is the cover story, but because it ties into the themes in Interzone 209, I’ll come back to that and consider the other contributions, first.

For the most part, this is light-hearted fare, The one exception, however, is John Lanagan’s. “Episode Seven: Last Stand Against the Pack in the Kingdom of the Purple Flower,” whose title might make you think it is fluff, but is in fact a bit more disturbing. A homage to end of the world survivor tales with mutant creatures devouring humans and strange fauna flourishing amidst abandoned technology, Lanagan offers a couple of new and interesting twists. One is the literally breathless narration, very long sentences I assume meant to mimic both the panic of the situation and the diction of Jackie, the college-aged pregnant protagonist. The other is that Jackie’s knight in shining armor, Wayne, is a comic books nerd whose ability to outsmart and kill the mutants comes from his reading material, and that he may be enjoying this comic-book-come-to-life a little more than he should. And that perhaps “what’s up” with Wayne may be more than that he’s found his niche in life as a mutant killer and protector of an expectant mother (whose child is not his) may involve some sort of possession beyond that of duty to a fellow creature in need. Nice reworking of a hackneyed scenario…Cormac McCarthy, eat your heart out!

Robert Reed’s “If We Can Save Just One Child…” uses a light touch to describe the serious issue of the increasing reliance of computer profiling to predict/identify child predators and how easy it is to get it wrong. While Reed’s description of how easy it is for the innocent to get wrongly accused is troubling because of its likelihood, the ending, in which a self-styled avenger of child abuse attacks the inaccurately profiled protagonist, in trying to be ironical and clever is a clunker in an otherwise engaging story.

“Wrong Number” by Alexander Jablokov posits a woman unlucky in love who finds a mechanic who can repair both automotive and karmic fender benders. The mechanic himself is in search of a lost love, but the woman hopes that his affection can be bent towards her through the use of a girlfriend who needs a past indiscretion straightened. Things work out, but not with a pat happy ending, because even in fantasy the way real life works out intrudes (it’s “wrong number” in a number of respects). And, sometimes, that’s all for the better. Nothing deep, here, but some amusing moments. File under “John Collier.”

In the tradition of Golden Age SF, Albert E. Cowdrey puts diplomats in outer space for “Envoy Extraordinary,” in which a pompous emissary serves as an unwitting tool for interstellar realpolitik. The protagonist is sufficiently unsympathetic that his desserts in this case might be considered just; the subsequent rehabilitation of his reputation as a hero is, alas, all-too recognizable in these days of Jessica Lynch and Mission Accomplished. Unlike what passes for politics in the real world, at least Cowdrey is making this up for the sole purpose of entertainment.

“Atalanta Loses at the Interpantheonic Trivia Bee” is, you guessed it, a retelling of the Greek/Roman myth in which the characters are updated to act like modern teenagers. In Heather Lindsley’s version, Atalanta isn’t running a race, but participating in the titular contest, and Hippomenes again wins her heart with golden apples, but this time they contain his key bodily parts. It all comes together with a nice closing line. Once again, nothing groundbreaking, but mildly diverting, though perhaps more so for fans of this particular myth.

Also clever, and also in the ancient legends camp, is Kevin Haw’s “Requirements for the Mythology Merit Badge” which, as you again guessed it, is just that. Some funny lines.

Of note on the non-fiction side, the always irascible Lucius Shepard takes aim at crummy movies in his regular “Films” column. A refreshing antidote to humdrum thumbs up/down reviews. Example: “Once were a director by the name of Lee Tamahoir, who made a movie, a very good movie, entitled Once Were Warriors, a powerful character study of a deracinated Maori family in the dead-end slums of Auckland. But that was a long, long time ago, back before he moved from New Zealand to Hollywood, started hanging out at L.A. fetish clubs and took to churning out pictures like xXx: State of the Union…”

The main attraction, here, though, is Chiang’s allegory, a sort of Arabian Nights-styled examination of the classic SF time travel dilemma. The alchemist of the title has constructed gateways through which you can pass twenty years into the future as well as, under certain circumstances, twenty years into the past. A merchant would like to take a journey, but has understandable concerns about the nature of time travel. Can you alter the future? Can you put to work what you learn about the future when you return to your own time? Even with knowledge of the future and past, is what will be immutable, and can the past be changed? Or, by virtue of going into the past, is your presence a determined part of what will happen because it has in fact happened, and any action you take to change them actually contributes to ensuring the course of events take place as you already know them. To answer these concerns, the alchemist tells a series of stories about a related group of people who made previous use of the gate.

These tales are, besides plot points that tie into a poignant moral, meditations on the art of storytelling itself, and the purpose of stories, a characteristic of much of so-called post-modern fiction. Which brings us to Interzone 209. For the silver anniversary issue, editor Andy Cox rounded up the usual suspects to commemorate the magazine’s longevity: M. John Harrison (a “good detective” in search of missing persons that’s a metaphor for a middle aged person’s search for self), Gwyneth Jones (a standalone story featuring characters from her Bold As Love series — nice to know she may still revisit there from time to time), and Alastair Reynolds (a post-apocalyptic England reverted to medieval existence in which a young girl is given a gift of “witchery”). There’s also Jamie Barras, with an alternate history involving the results of a Nazi scientific experiment. As an extra gift, and extra to the physical magazine, you can still download for free the always amusing Edmund Morris and his signature “cast of thousands” of historical figures who populate “Journey to the Center of the Earth.” But I’d like to focus on the contributions of Hal Duncan and Daniel Kaysen, which share interesting perspectives on the role of the author and the pitfalls of imagination.

These tales are, besides plot points that tie into a poignant moral, meditations on the art of storytelling itself, and the purpose of stories, a characteristic of much of so-called post-modern fiction. Which brings us to Interzone 209. For the silver anniversary issue, editor Andy Cox rounded up the usual suspects to commemorate the magazine’s longevity: M. John Harrison (a “good detective” in search of missing persons that’s a metaphor for a middle aged person’s search for self), Gwyneth Jones (a standalone story featuring characters from her Bold As Love series — nice to know she may still revisit there from time to time), and Alastair Reynolds (a post-apocalyptic England reverted to medieval existence in which a young girl is given a gift of “witchery”). There’s also Jamie Barras, with an alternate history involving the results of a Nazi scientific experiment. As an extra gift, and extra to the physical magazine, you can still download for free the always amusing Edmund Morris and his signature “cast of thousands” of historical figures who populate “Journey to the Center of the Earth.” But I’d like to focus on the contributions of Hal Duncan and Daniel Kaysen, which share interesting perspectives on the role of the author and the pitfalls of imagination.

Post-modernism revels in the unreliable narrator and/or pointing the finger at the man behind the curtain. Such literature goes out of its way to remind readers they are immersed in a “fiction” made up by the author, who may or may not be a character in his own tale. This can in part have religious allusions — the responsibilities and roles of God in relation to his creation — as well as secular considerations of any artistic endeavor — is art an unchangeable object for one-way “consumption,” or is there some kind of interaction in which the “value” or “meaning” of the work is in a constant state of flux, depending on the participation and biases of the particular consumer/reader/viewer?

Of the two, Kaysen’s “Tears for Godzilla” is the more straightforward, though that’s only in comparison to Duncan’s high scoring weird quotient. The obvious comparison is to Philip Dick. The narrator is an author, fairly famous in the horror genre, in love with, or at least infatuated with, a woman named Amanda. Horrific things happen to both of them in subsequent scenarios that change slightly in details and events. What’s real, and what is part of the narrator/author’s imagination? And does it matter much whether it is real or not? Isn’t the real question whether or not any of it’s true, even if it is made up?

The point Kaysen (or his creation, the narrator of the story, who both are and are not the same) makes is the longstanding conceit that art arises from the confrontation of personal demons:

I almost cry then, by the window, for Godzilla, for everyone trapped in the grey who won’t now be saved.

And then I realize: all my stories are tales of pain and monsters. But the monsters are good and do not cause the pain.

p. 53

What I think this means is the monsters — the dreams, the imagination, the longings — are only bad insofar as we act upon them in irrational ways. Properly channeled — as, say, in a piece of fiction, or perhaps towards a love interest — our demons can be put to constructive use. Whether they terrify or inspire is up to us.

Trying to figure out what Duncan means is quite another matter. I haven’t yet read his duology, Vellum and Ink, but the general rap on them is that while difficult reading, it’s ultimately worth the effort of plowing through. I have read some of Duncan’s shorter works, and that description certainly holds true as well for them; “The Whenever at the City’s Heart” is no exception. The story is preceded by an interview, where Duncan speaks of his “weird 3D time approach.” I’m not quite sure what that means, but, as far as I can figure out, it’s got something to do with using multiple viewpoints to depict an event of some kind of cataclysmic importance. The titular city’s heart in this particular case has something to do with a clock. Such a mechanism, of course, metaphorically resonates as the mechanistic workings of the universe, which measures out not only time, but the gears and pulleys that define reality. Something is awry with the mechanism. The destruction of the mechanistic model paves the way for a different cosmology, one rooted more in the Tao of metaphysics than Newton — string theory anyone?

That’s what it’s about — sort of, I think. What’s somewhat intriguing is Duncan’s description of what might be seen as directions for reading his work:

The thing looks like nonsense when it’s opened at first, incoherent, inchoate, but…after a while of reading there’s a strange cohesion to it. The words are jumbled things – riverrun and passencore and such — confusions with no single meaning; rather it’s as if the meaning of the parts is made out of the meaning of the whole. The reader has to read it…outside-in, let the senseless prosody, the seeming gibberish of poetry and idiom wash over them until the thresholds of theme come clear. Reaching the end of it, he’d known that there was sense there, not built of blocks to be constructed, but rather in the singularity of it, the text as a whole. The end is the starting point and only in understanding that does it begin to break down into acts then chapters, sections, paragraphs then sentences of sorts and, finally, into the words and morphemes that can be decrypted. He hefts it in his hand, this enigmatic, infuriating text.

p. 19

Well, that about sums it up, doesn’t it?

Something to ponder, until next we meet…