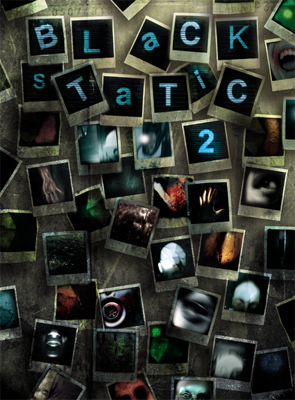

Short Fiction Reviews: Black Static #1 and #2

By David Soyka

Copyright 2008 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

The Third Alternative (TTA), a quarterly magazine whose title suggested alternative horror, slipstream (whatever that is) and science fiction that might be considered too “edgy” for the mainstream, first appeared way back in 1994. When editor/publisher Andy Cox acquired long-running British science fiction magazine Interzone in 2005, he put TTA on hiatus after forty-two issues. The initial reasoning was to focus on revamping the graphically- (and some would say content-) challenged Interzone. Cox also retired the TTA nameplate (though keeping it for the name of his publishing company, TTA Press) and promised to re-launch it as a venue dedicated exclusively to dark horror under a new title of Black Static. As Cox explains, “With the arrival of Interzone…it no longer made sense to compete with it for sf or fantasy, so we took the opportunity to tilt TTA fully towards the darker side, which had always been its more dominant side. The change in title is intended to emphasize this shift…”

The Third Alternative (TTA), a quarterly magazine whose title suggested alternative horror, slipstream (whatever that is) and science fiction that might be considered too “edgy” for the mainstream, first appeared way back in 1994. When editor/publisher Andy Cox acquired long-running British science fiction magazine Interzone in 2005, he put TTA on hiatus after forty-two issues. The initial reasoning was to focus on revamping the graphically- (and some would say content-) challenged Interzone. Cox also retired the TTA nameplate (though keeping it for the name of his publishing company, TTA Press) and promised to re-launch it as a venue dedicated exclusively to dark horror under a new title of Black Static. As Cox explains, “With the arrival of Interzone…it no longer made sense to compete with it for sf or fantasy, so we took the opportunity to tilt TTA fully towards the darker side, which had always been its more dominant side. The change in title is intended to emphasize this shift…”

Well, time flies, but the resurrection has finally arrived and Cox seems to be (so far) on track with a regular publishing schedule, albeit with some initial glitches, in which Black Static alternates every month with Interzone. Subtitled “Transmissions from Beyond” (a slight variation on TTA‘s last tag line of “Transmission from the Edge”), longtime readers are likely to feel that you can go home again. While slightly smaller in size, the format is familiar, with weird cover art (though not quite as bizarrely gruesome as in the past) and black-and-white interior artwork that emphasizes juxtapositions of strange, disorienting images. In fact, the style may be familiar to new readers who come to the magazine by way of the revamped Interzone, which is stylistically similar, particularly since the last two issues I’ve seen have moved away from a glossy color interior to a kind of lifeless black and white. (Cox says that the decision to print Black Static in black and white is not a cost savings measure — as may have been the case with Interzone, which may at some point return to color — but reflective of its subject matter. However, the matte paper stock makes everything look a little dull, which apparently the publisher realizes.) There’s also the “usual suspects,” such as Christopher Fowler’s sardonic column and Peter Tennant’s book reviews.

As for the main event — the fiction — Black Static delivers what you’d have expected from its predecessor: warped fairy tales, decayed urban settings, relationships gone wrong in decidedly strange ways, encounters with peculiar people. Happy endings are the exception, rather the rule.

One possible exception, however, from the premier issue is “Bury the Carnival” by Simon Avery, a re-imagining of Pinocchio in which Gepetto is a dope smoking misanthrope barely tolerated within an Eastern European-like village governed by a Puritan social order. This story could have ended when the narrator discovers her true identity about midway through the tale, but then it goes on to provide a seemingly redemptive ending. I say “seemingly” because, in the context of this tale, the fact that a character’s return to the forest where he’s chopping wood to heat his cabin could be taken two ways…

Such ambiguity is a Black Static hallmark because, well, life is pretty ambiguous. Even when it involves crossing over into a dream state, as in Daniel Bennett’s “Action Undream,” or an unfortunate tryst that leads a man to spend a thirty-year career in the missing persons bureau before discovering where lost souls go in “My Stone Desire,” by Joel Lane, in which these desires are literally laid in concrete. “Pale Saints and Dark Madonnas” by Jamie Barras recounts a storm in Rio that demonstrates the weird clashes of “civilization” with indigenous culture.

But the weirdest, and the best, story here is “Votary” by M. K. Hobson. A daughter’s obese father sits naked in the cellar. He must be fed quantities of food and other oral satisfactions:

When they got home, Mon would bring the bags downstairs into the basement. She would open the bourbon and all the packs of cigarettes and all the cheeseburgers and she would pour everything into father’s mouth. His jaw unhinged like a big door opening, a big half-circular door on coiled springs, expanding until he was like a living caldera, bulbous and shapeless below, deep and round above. Then Mom poured everything in….

— p. 38

But if Votary’s mother fails to provide the father with sustenance, who will? A monster story of Freudian implications.

The issue concludes with another seemingly happy ending. In “Lady of the Crows,” a failed actor reduced to being a theater manager tries to avoid a former lover appearing in a play about a woman who poisons her husbands. It turns out that the former lover is narcoleptic, and the theater manager fears that she is in danger having fallen asleep in her dressing room long after hours. Here, the play’s the thing by which to catch the conscience — and save the life of — the protagonist.

The issue concludes with another seemingly happy ending. In “Lady of the Crows,” a failed actor reduced to being a theater manager tries to avoid a former lover appearing in a play about a woman who poisons her husbands. It turns out that the former lover is narcoleptic, and the theater manager fears that she is in danger having fallen asleep in her dressing room long after hours. Here, the play’s the thing by which to catch the conscience — and save the life of — the protagonist.

If the second issue seems a bit stronger, it’s because the lead-off story by Lisa Tuttle and Steven Utley, “In the Hole,” sets the pace. The protagonist is a war veteran returning to a fiancé who has waited all these years for him, but homecoming, not to mention the sex, is not what he expected. “Heath gazed out at the misty landscape and tried to make sense of what he saw. Although he had grown up in this country, it had become alien to him” (p.5). This is surrealism in service of psychological truth.

In “The Serpent and the Hatchet Gang,” F. Brett Cox blends two apparent incidents in nineteenth-century New England history that otherwise wouldn’t be connected together — the sighting of a “sea serpent” and the largely women’s-based temperance movement. While the “feminist message” strikes me as a little heavy handed, there’s some nice imagery in combining the two strands.

Scott Nicholson’s “Must See to Appreciate” is another of my favorites, a view of a shady real estate transaction that goes sour, with a twist. It nicely gets into the “head” of a realtor desperate to make a sale, hoping to be hide a property’s drawbacks, which in this case are not what you might think.

“The moment you name something you change what it was, what it was becoming. It was a living evolving thing, and then you killed it by naming it” (41). So says the nameless character in “Unknown,” by Steve Rasnictem, which is about just that. It is also about the nature and structure of fiction; similarly, “In the Shape of a Dragon,” by Melanie Fazi (and translated from the French by Brian Stableford) considers the causes — and curses — of artistic inspiration.

You could file Lynda Rucker’s “Ash Mouth” under Southern Gothic; the Ash-Mouth of the title is what Ivy’s grandmother tells her comes for you when you die. Now grown up, Ivy is a scientist with a rational view of how the universe works; yet, she has reason to wonder if the Ash Mouth came for her sister, or, years later, her grandmother? How we perceive, or misperceive, reality, is also the subject of Andrew Humphrey’s “Holding Pattern,” with tragedy resulting when things get out of joint.

All in all, an auspicious return, demonstrating that some things are worth waiting for.