R.A. Lafferty: An Attempt at an Appreciation

A little while ago, John O’Neill posted a news item on this blog about the literary estate of R.A. Lafferty (1914-2002) being put up for auction, with the current bid being $70,000 for the copyright to all his works. It’s an odd development, but then Lafferty was an odd writer. I want to try to say something about his work here, not because I’ve read everything he’s written — I’ve read only a fraction of his output, which runs to over two dozen novels and two hundred short stories — but because he’s a writer strong enough to have hooked me to want to read more. And I want to say something about why.

A little while ago, John O’Neill posted a news item on this blog about the literary estate of R.A. Lafferty (1914-2002) being put up for auction, with the current bid being $70,000 for the copyright to all his works. It’s an odd development, but then Lafferty was an odd writer. I want to try to say something about his work here, not because I’ve read everything he’s written — I’ve read only a fraction of his output, which runs to over two dozen novels and two hundred short stories — but because he’s a writer strong enough to have hooked me to want to read more. And I want to say something about why.

Which is tricky, because that means having to identify what it is that Lafferty does that’s so intriguing. And I think much of what is powerful in his work comes from its sense of strangeness. Almost all of his writing feels like nothing else; not like a traditional sf tale, not like a New Wave tale, not like typical fantasy or horror, less like a mainstream writer trying out genre. You could say there’s something folkloric, but not mythic to it; so it’s become almost a truism to say that Lafferty wrote tall tales. It’s an accurate statement, but what does it mean?

To start with, Lafferty explodes the old bad advice about showing, not telling. He tells, and he tells with confidence. He tells us what the world is like, how it works, who his characters are. And by being so confident, by moving on to things happening for which we have not really been prepared by the telling of other things, he makes it work. Dickens doesn’t waste time showing us Marley’s death scene, he tells us straight out at the start of things that Marley’s dead as a door-nail; that first sentence still doesn’t really prepare us, the first time we read or hear the story, for Marley’s ghost, much less the three ghosts that follow. Lafferty’s work is a little like that, the powerful strangeness we once knew in stories, in science fiction, recaptured.

To start with, Lafferty explodes the old bad advice about showing, not telling. He tells, and he tells with confidence. He tells us what the world is like, how it works, who his characters are. And by being so confident, by moving on to things happening for which we have not really been prepared by the telling of other things, he makes it work. Dickens doesn’t waste time showing us Marley’s death scene, he tells us straight out at the start of things that Marley’s dead as a door-nail; that first sentence still doesn’t really prepare us, the first time we read or hear the story, for Marley’s ghost, much less the three ghosts that follow. Lafferty’s work is a little like that, the powerful strangeness we once knew in stories, in science fiction, recaptured.

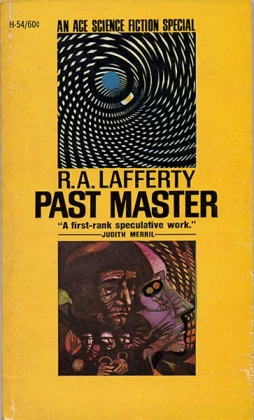

The flip side is that there’s not much of a sense of character in his work. To some extent character emerges in his longer work, but even there it feels (at least in what I’ve read) less distinctive or carefully wrought so much as an elaboration of a simple flat notion to meet a series of peculiar events. When Lafferty brings back Thomas More from the dead in his novel Past Master, the result feels less like an exploration of Thomas More as a character than an exploration of the idea of Thomas More and what that idea meant to the unfolding of history.

This isn’t to say that his characters are dull, or that they are not distinctive. You know who they are, certainly. But that’s not because they’re vivid, with a real individual subjectivity that comes out of a specific situation in time and place and culture; that is, it’s not because they’re traditional rounded characters. It’s because, I think, they’re ideas of characters. They’re characters in a tall tale, who have the elements to them that they must have, plus whatever else the tale-teller thinks the tale can bear; whatever keeps things moving and keeps things entertaining and makes for an unusual shape. But at the same time, whatever doesn’t surprise us about the kind of character they are.

You could say that Lafferty, as a tall-tale-teller, plays with archetypes; but I think he also, and consciously, plays with stereotypes. Some of which have not worn well. So his tales are filled with competent professional men who lose themselves in work; with flighty women who are half-allied to the strangeness beyond rational thought. Occasionally there’s a moneylending (or money-making) Jew. Black Africans “long of ankle and metatarsus and lower limb so they can run and leap uncommonly”. But here’s a question: as a tall-tale-teller, is he using these stereotypes, or is he using his audience’s awareness of these stereotypes? Sometimes I think it’s the one; sometimes I think it’s the other; often I think that these stories read as though they were written a long time ago, in their rhythm and their shape. And that they come out of the archetypes and stereotypes of a world that is different from this one.

You could say that Lafferty, as a tall-tale-teller, plays with archetypes; but I think he also, and consciously, plays with stereotypes. Some of which have not worn well. So his tales are filled with competent professional men who lose themselves in work; with flighty women who are half-allied to the strangeness beyond rational thought. Occasionally there’s a moneylending (or money-making) Jew. Black Africans “long of ankle and metatarsus and lower limb so they can run and leap uncommonly”. But here’s a question: as a tall-tale-teller, is he using these stereotypes, or is he using his audience’s awareness of these stereotypes? Sometimes I think it’s the one; sometimes I think it’s the other; often I think that these stories read as though they were written a long time ago, in their rhythm and their shape. And that they come out of the archetypes and stereotypes of a world that is different from this one.

But that oddness of shape; that is key to them, I feel. The structure of these stories is almost always unpredictable. Once we think we know where the story’s going, we find it shift to something else; once we think we’ve grasped the scale he’s working with, it becomes bigger than we suspected. A story about a man stranded on a planet of spiders becomes a tale of a horror destroying humanity. A story about a genius who can’t understand mundane society, by sudden sleight-of-hand, becomes a story about inhumanly brilliant con men; and I can’t help but think Lafferty plays his stories like cons, with misdirection and canniness and, often, an unpredictable individual touch to put the whole mess over.

There’s no playing with traditional genre rules, as such. His stories are what they are, be what they may. They mix horror and fantasy and science-fiction and, frequently, humour. If you think there’s a specifically American approach to the tall tale, and if you think that science fiction is specifically associated with America (and especially twentieth-century America), then you can say it’s a weird fusion of American sensibilities, told in an oddly American voice; dry, cantankerous, demotic. It’s a wiseass voice, which heightens the sense of horror immeasurably.

And I think it’s the voice that may be key to the work. In fiction so filled with shifts and disjunctions as Lafferty’s, it’s the smooth and sure voice of the teller that keeps the audience going past the tricky bits. But then the voice also is filled with shifts and disjunctions; the diction will change, here and there, or a story told in the omniscient third-person suddenly questions itself, or uses some distinctive turn of phrase, and the narrator then becomes personalised, and we are reminded, not unpleasantly, that this is a tale we are being told.

And I think it’s the voice that may be key to the work. In fiction so filled with shifts and disjunctions as Lafferty’s, it’s the smooth and sure voice of the teller that keeps the audience going past the tricky bits. But then the voice also is filled with shifts and disjunctions; the diction will change, here and there, or a story told in the omniscient third-person suddenly questions itself, or uses some distinctive turn of phrase, and the narrator then becomes personalised, and we are reminded, not unpleasantly, that this is a tale we are being told.

The voice echoes the structure. In Lafferty’s fiction, narrative rules that you think you understand can be pulled away at any moment to show that Lafferty’s actually operating by bigger, more profound rules than you ever knew existed. The flatness of his characters lets things happen to them that would take forever to set up with more rounded characters. So the stories are told almost always from the outside of the characters, rarely in first person, but always from inside the skin of a storyteller. As though the tale was being pulled out of him.

Stylistically, the writing is terse. It is direct and driving. And because not a word is wasted, and because any tale can turn on a dime on any one of those words, you’re forced to read carefully, attentively. And are rewarded when you do. And are surprised when you finish, and find the worlds-upon-worlds of the tale were created in ten pages or a dozen, or when you look back over a longer work and realise how much of it there was.

Lafferty’s work struck me as reading oddly like the missing term between Lord Dunsany and Harlan Ellison. There’s the sense of wonder and unpredictability of the first, the precision and detail and exuberance with structure and language of the second. Ultimately I think Lafferty’s more similar to the fable-like Dunsany, but he most often writes with Ellison’s ferocity; perhaps more precisely, with a bleakness beyond Ellison’s. Which, offset by the Dunsanian wonder, creates the horror and weirdness of the tales.

Lafferty’s work struck me as reading oddly like the missing term between Lord Dunsany and Harlan Ellison. There’s the sense of wonder and unpredictability of the first, the precision and detail and exuberance with structure and language of the second. Ultimately I think Lafferty’s more similar to the fable-like Dunsany, but he most often writes with Ellison’s ferocity; perhaps more precisely, with a bleakness beyond Ellison’s. Which, offset by the Dunsanian wonder, creates the horror and weirdness of the tales.

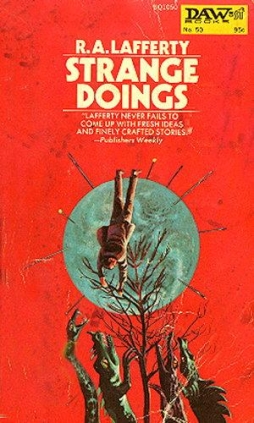

I’ve heard it said that Lafferty was a writer’s writer; certainly he’s had an effect on writers that seems to have been greater than the response from the general sf audience. Neil Gaiman, for example, was a fan of Lafferty’s, and you can see it in his work; among Lafferty’s stories in the anthology Strange Doings are tales of a world physically changed by many people dreaming the same dream every night, and immortals meeting for dinner once a century as the world changes around them — and both these things return, wonderfully changed, in Gaiman’s Sandman comic.

Let’s say that Lafferty does have a special appeal to writers (and you can see some more praise here, part of this site). Why so? I couldn’t say why Lafferty’s work wouldn’t appeal to non-writers, except perhaps to say that he didn’t investigate his matter in depth or realistic detail, and used recurring characters infrequently — one example, and to describe him is perhaps to give a sense of Lafferty’s imagination, is Willy McGilley, oldest of the Wrecks, a race of genius con-men descended from a brother of Adam; Willy mostly appears in passing, less a character than a symbol. Mention of McGilley could be seen to tie stories together, but mostly, I think, he’s a notion that means something to Lafferty, and so the name gets used, and infrequent readers need never notice that he’s turned up before.

But in general I think Lafferty does two things that, while they’ll impress anyone, I suspect particularly appeal to writers. First, he uses language distinctively, imaginatively, and with great resource. You’ll be introduced to new words in Lafferty, but not obtrusively. They’re just the right words for the job, that’s all. And you’ll be introduced to new combinations of words, phrases made up of words put together in an order nobody’s ever imagined before.

But in general I think Lafferty does two things that, while they’ll impress anyone, I suspect particularly appeal to writers. First, he uses language distinctively, imaginatively, and with great resource. You’ll be introduced to new words in Lafferty, but not obtrusively. They’re just the right words for the job, that’s all. And you’ll be introduced to new combinations of words, phrases made up of words put together in an order nobody’s ever imagined before.

Second, he’ll spark your own imagination. His stories are so dense, ready to explode like a cranky jack-in-the-box, that they can’t help but open your eyes to new possibilities for fiction, new ways to do things. He’s not just full of ideas himself, but the spark for ideas in others. His writing is imaginative in the fullest, most rewarding sense.

Such, at least, is what I have found in the works of his that I’ve read. I hope whatever happens with his estate leads to his work becoming more accessible, and more known. Sometimes a writer off the beaten track, a writer peripheral to the development of a tradition, is worth returning to, worth re-examining as a source for further inspiration. So, it seems to me, is Lafferty. I look forward to learning more form his work; I look forward to reading more.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

Well said.

If I may say so, you have made noticeable improvements in this kind of blogging/posting/whateveryoucall it, Surridge.

I am a Lafferty reader, for certain and prefer his work, to many from his ‘generation.’

Besides the obvious influence on Gaiman, you can see some upon Wolfe.

Also note that Wolfe, and Lafferty are from the southwestern U.S., ( and so too Howard ) and the work of ( all 3 ) of these men upon analysis shows the footprint of the ‘American Tall-tale.’

Hi, Radiant. Thanks for the good words! (Sorry for the delayed reply.)

I think you’re quite right that you can see similarities to Wolfe. (Actually, Wolfe’s another guy who influenced Gaiman, too.) And you’re also right, I think, about Howard and tall tales. It’s interesting to see how Howard and Lafferty took that same sort of influence and used it in different ways. Interesting, also, to think of Conan or Solomon Kane as being in the same sort of tradition as the stories about Davy Crockett or John Henry …

[…] read, I note Dick’s The Man in the High Castle, a book he wrote by consulting the I Ching, and R.A. Lafferty’s Past Master, a book that is frankly like little else I know. Going on through the list (and […]