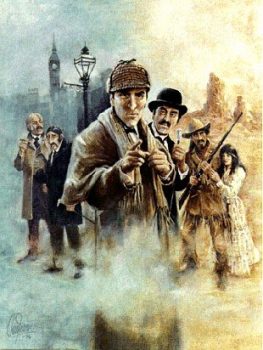

The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes: The Case of the Inferior Sleuth (Doyle on Holmes)

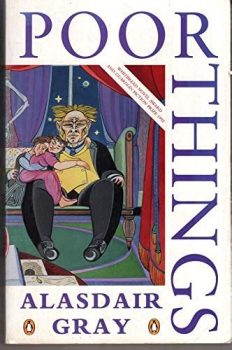

Welcome to week four of Doyle on Holmes. We started with The Truth Behind Sherlock Holmes. Then, it was Some Personalia about Sherlock Holmes. Last week, A Gaudy Death. This week, it’s a poem war featuring Sir Arthur! All four of these essays can be found in Peter Haining’s The Final Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. It’s a good book, and the only partial replacement I’ve found for Jack Tracy’s cornerstone book, Sherlock Holmes: The Published Apocrypha.

The Science of Deduction is the second chapter of A Study in Scarlet – the first Sherlock Holmes story. Holmes had explained the observations and inferences that had led to the famous line, “You have been in Afghanistan, I perceive.” Watson then – for the first, but certainly not the last, time – says it’s a simple matter. Watson then tells Holmes that he reminds him of Poe’s Dupin, and he didn’t know such existed in real life. Holmes sets him straight:

“Sherlock Holmes rose and lit his pipe. ‘No doubt you think that you are complimenting me in comparing me to Dupin,; he observed. ‘Now, in my opinion, Dupin was a very inferior fellow. That trick of his of breaking in on his friends’ thoughts with an apropos remark after a quarter of an hour’s silence is really very showy and superficial.

It’s Elementary – Bearing in mind this the very first story, having Holmes say that is pretty funny. Since he would do exactly that with Watson, more than once.