The Return of a Classic Fantasy Hero: A Review of T.C. Rypel’s Dark Ventures

|

|

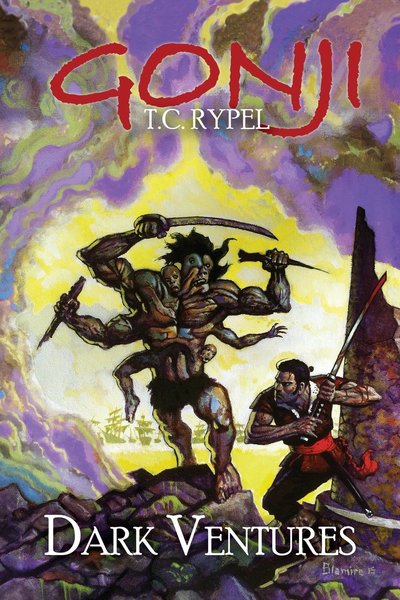

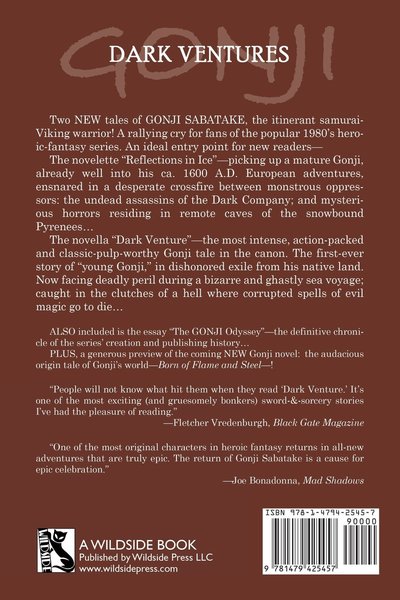

Dark Ventures by T.C. Rypel

Wildside Press (212 pages, $14.99 in paperback/$4,99 digital, March 16, 2017)

Original cover painting by film director Larry Blamire (The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra)

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, many authors were churning out their own versions of big, iron-muscled barbarian heroes like Conan of Cimmeria. There were exceptions, of course, like Michael Moorcock, Fritz Leiber, and Jack Vance, to name three authors I’ve always favored. But then along came T.C. Rypel, who hit the ground running with something different, something uniquely his own… his character of Sabatake Gonji-no-Sadowara, the half Scandinavian and half Japanese samurai.

Gonji was truly a breath of fresh air in the genre of Sword and Sorcery, although I think Rypel’s novel are much more epic and actually closer to Heroic Fantasy in scope and theme. His setting wasn’t some imaginary world filled with ancient gods, powerful warlocks and fanciful kingdoms, but was instead deeply rooted in and around Romania and the Carpathian Mountains of the 16th century. Perhaps a parallel world, but close enough to the Europe of that era to lend it a flavor of historical reality. Besides the non-barbaric character of Gonji, who was introspective, poetic, and humble, as well as a total bad ass with a sly sense of humor, what also set Rypel’s novels apart from so many others was the fact that he worked gunpowder and firearms into his stories, right along with the sorcery and creatures and other elements of the fantastic. And like Robert E Howard’s Solomon Kane before him, Rypel made it all work, too.