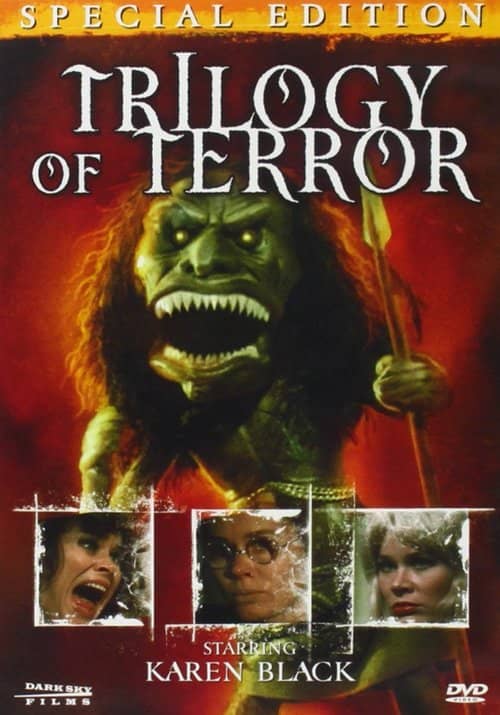

Movie of the Week Madness: Trilogy of Terror

Wednesday, March 5, 1975 dawned cool and cloudy in Los Angeles, as Sergeant Friday used to say. Among the usual topics of conversation that morning during snack break at my high school, one question predominated: Did you see that show last night?! The show in question was the previous evening’s ABC Movie of the Week: Trilogy of Terror. Yeah, that one. The one with the “Zuni fetish doll” that comes to life and wreaks havoc with Karen Black’s apartment, to say nothing of her epidermis.

The ABC Movie of the Week ran for six seasons, from 1969 to 1975, and was one of the first series comprised entirely of movies made specifically for television. Running once (in some seasons, twice) a week, and featuring the usual tv movie aggregation of performers, all fitting into the categories of has-been, never-was, and hoping-to-be (many of whom were shackled to the oars of some other ABC series, naturally), the Movie of the Week presented stories from all genres. Comedy, romance, romantic comedy, western, crime, social issue (unemployment, drug use, the problems of the young and of the aged, and alcoholism were… well, popular is the word, I guess, and 1972’s That Certain Summer is a genuine landmark, being the first American film of any sort to deal with homosexuality in a non-biased manner), disease-of-the-week (remember Brian’s Song?), and what used to be called the war between the sexes all made regular appearances.