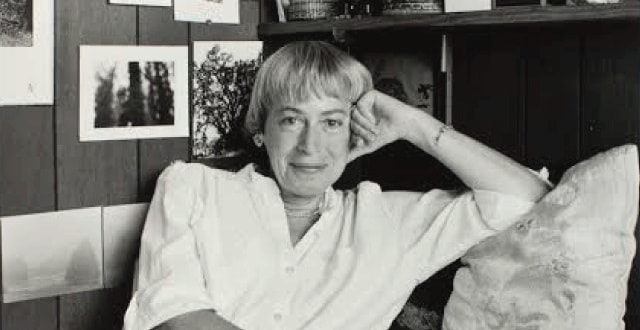

Ursula K. Le Guin, October 21, 1929 – January 22, 2018

Ursula K. Le Guin, one of the greatest SF writers of the 20th Century, died yesterday.

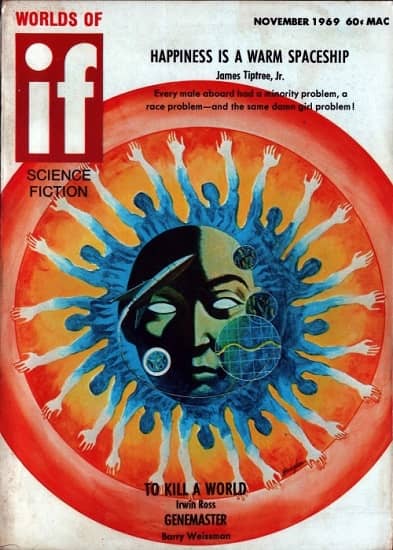

Le Guin was equally at home in both science fiction and fantasy, and won virtually every accolade our field has to offer. Her novel The Dispossessed (1974) won the Locus, Nebula, and Hugo Awards, The Left Hand of Darkness (1969) won both the Hugo and Nebula, and her Earthsea novel The Other Wind (2001) won the World Fantasy Award. The third Earthsea novel, The Farthest Shore, won the 1973 National Book Award. She won the Hugo Award in virtually every category available to writers, including Best Short Story (“The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas,” 1974), Best Novelette (“Buffalo Gals, Won’t You Come Out Tonight,” 1988), Best Novella (The Word for World Is Forest, 1976), and Best Related Work (her essay collection Words Are My Matter, 2016). She won the Locus Award a record nineteen times. Unlocking the Air and Other Stories was one of three finalists for the 1997 Pulitzer Prize.

In 1995 Le Guin was presented with the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement, and in 2003 she became a SFWA Grand Master Award, the highest honor bestowed by the Science Fiction Writers of America. The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted her in 2001, and in April 2000 the U.S. Library of Congress made her a Living Legend in the “Writers and Artists” category. In 2016 The New York Times described her as “America’s greatest living science fiction writer.”