Birthday Reviews: Wyman Guin’s “Trigger Tide”

Wyman Guin was born on March 1, 1915 and died on February 19, 1989. Guin only published seven stories and one novel, The Standing Joy during his career. His most famous stories may have been “Beyond Bedlam” and “Volpla,” the latter of which was adapted for the radio show X Minus 1 in August 1957. Guin was declared the winner of the Cordwainer Smith Rediscovery Award in 2013.

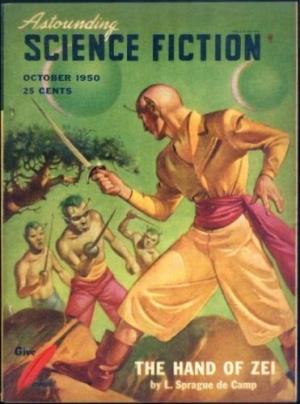

Guin’s first story was “Trigger Tide.” When it was first published in Astounding in October 1950, edited by John W. Campbell Jr., it appeared under the pseudonym Norman Menasco, although Guin reverted to his own name for his second story, “Beyond Bedlam.”

The story was reprinted by Groff Conklin in Omnibus of Science Fiction and was included in his collection Living Way Out (a.k.a. Beyond Bedlam). It was again reprinted in The World Turned Upside Down, edited by Eric Flint, David Drake, and Jim Baen.

Guin’s story is about an agent on a distant planet who is trying to assassinate a fascist leader, a task assigned to earlier agents who have failed. When the story opens, he is lying, beaten, on a shelf of quartzcar near the beach and must try to get away from the shore before the tide comes in.

The setting is the most intriguing part of the story. The world is made up of archipelagos of quartzcar. The crystalline structure of the material means that any landmass above the water line is a series of shelves. In addition, the five moons orbiting the planet caused a wide variation of tides. Furthermore, the tides wreaked havoc with the piezoelectrical currents inherent in the quartz.

The impact of this strange situation is felt at the climax of the story, which doesn’t feel like a deus ex machina only because the story feels like it is a set up to exploit the strange parameters of the world.