In 500 Words or Less: Tales of the Captain Duke by Rebecca Diem

Tales of the Captain Duke

Tales of the Captain Duke

By Rebecca Diem

Woolf Like Me (paperback/ebook editions, price varies, Aug 2014 – May 2018)

For anyone who reads this column even semi-regularly, this next review is probably gonna seem out of place. But indulge me for a few minutes to talk about Tales of the Captain Duke, a four-part series of indie novellas by Toronto author Rebecca Diem.

First thing to make clear: these novellas are equal parts steampunk adventure and romance, which is obviously not my usual cup of tea, so the fact that I’m reviewing it here should tell you something. Because honestly, I got swept up in this series. Why? Besides the fact that airships and pirates and steampunky technology are really cool, these novellas focus on character, which is always the number one thing I look for in a series.

Though the title is Tales of the Captain Duke, the focus is really on Clara, a debutante who leaves her life of wealth by sneaking away on an airship and falls in with “pirates” standing up to economic tyranny and corruption, under the leadership of the legendary Captain Duke. Okay, maybe that sounds like an obvious romantic setup – especially as the attraction between Clara and her new Captain is made clear – but Clara is far from your stereotypical female character.

She’s a badass, and quickly becomes an important part of the Captain Duke’s crew, joining a group of nuanced characters who go through a series of arcs from the first novella to the last. For example, you have first mate Trick, who becomes a vehicle for exploring physical disability when he relearns how to make music with a prosthetic arm, and youths Cat and Mouse, who desperately want to be adults and contribute more to their captain’s operations but have a lot to learn before they can.

This character work is tied into detailed, thought-out worldbuilding beyond the usual Victorian steampunk. Remember that this is an adventure story, too, complete with plenty of action and danger. Admittedly, this isn’t a story about elaborate twists and turns or huge surprises; when things from Clara’s past get mentioned off hand, you know they’re going to play a greater role later on, and when the Captain Duke’s people get betrayed, the culprit is pretty clear. That isn’t a bad thing, by any means. I love what Patrick Rothfuss calls “big fat fantasy books,” but sometimes I need a story that’s straightforward and fun, too, which Diem delivers in this series.

I had time for one more movie in the Fantasia screening room before I’d head over to the J.A. De Sève Theatre to watch a film called Madeline’s Madeline, an experimental film about a girl in a theatre group struggling to define herself. It’d be the last movie I’d see in the De Sève at this year’s festival, but before it started I opted to watch a Finnish comedy about death metal. (There’s a reason for that choice, involving the final film of the festival; more on that in a few posts.)

I had time for one more movie in the Fantasia screening room before I’d head over to the J.A. De Sève Theatre to watch a film called Madeline’s Madeline, an experimental film about a girl in a theatre group struggling to define herself. It’d be the last movie I’d see in the De Sève at this year’s festival, but before it started I opted to watch a Finnish comedy about death metal. (There’s a reason for that choice, involving the final film of the festival; more on that in a few posts.)

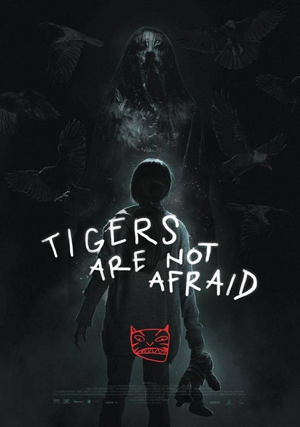

I was at the Fantasia screening room early on August 1 to watch a movie I’d missed when it played in a Fantasia theatre: Tigers Are Not Afraid (Vuelven), written and directed by Issa López. I’d heard a number of people around the festival rave about it, and I was intrigued. 10-year-old Estrella (Paola Lara) is a girl in a Mexican city ravaged by drug violence. When her mother goes missing, she falls in with a gang of four boys who live on the street. But their leader, a scarred child named Shine (Juan Ramón López), has stolen a cell phone containing a video incriminating an aspiring local politician (Tenoch Huerta) in brutal criminal activity. Now his cartel’s after them, and death is all around. So, perhaps, is magic; but magic is not always safe.

I was at the Fantasia screening room early on August 1 to watch a movie I’d missed when it played in a Fantasia theatre: Tigers Are Not Afraid (Vuelven), written and directed by Issa López. I’d heard a number of people around the festival rave about it, and I was intrigued. 10-year-old Estrella (Paola Lara) is a girl in a Mexican city ravaged by drug violence. When her mother goes missing, she falls in with a gang of four boys who live on the street. But their leader, a scarred child named Shine (Juan Ramón López), has stolen a cell phone containing a video incriminating an aspiring local politician (Tenoch Huerta) in brutal criminal activity. Now his cartel’s after them, and death is all around. So, perhaps, is magic; but magic is not always safe.

On Tuesday, July 31, the first movie I planned to see alongside a general audience was a Hong Kong action movie called The Brink. After that, I’d pass by the screening room before heading home. There’d be only two more days of Fantasia after this one, and I wanted to catch up on things I’d missed in theatres. I was specifically curious about a Korean movie called The Outlaws, about a cop who’s working against the clock to catch a Chinese gang who’re trying to take over territory in a district of Seoul. Two promising action movies; I had reasonable hopes for the afternoon.

On Tuesday, July 31, the first movie I planned to see alongside a general audience was a Hong Kong action movie called The Brink. After that, I’d pass by the screening room before heading home. There’d be only two more days of Fantasia after this one, and I wanted to catch up on things I’d missed in theatres. I was specifically curious about a Korean movie called The Outlaws, about a cop who’s working against the clock to catch a Chinese gang who’re trying to take over territory in a district of Seoul. Two promising action movies; I had reasonable hopes for the afternoon.