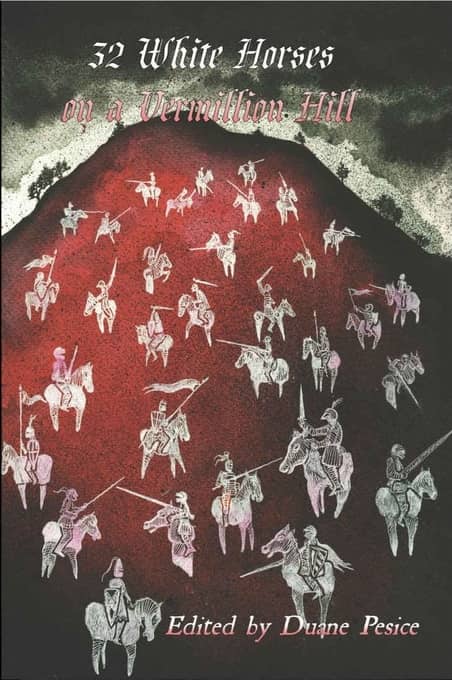

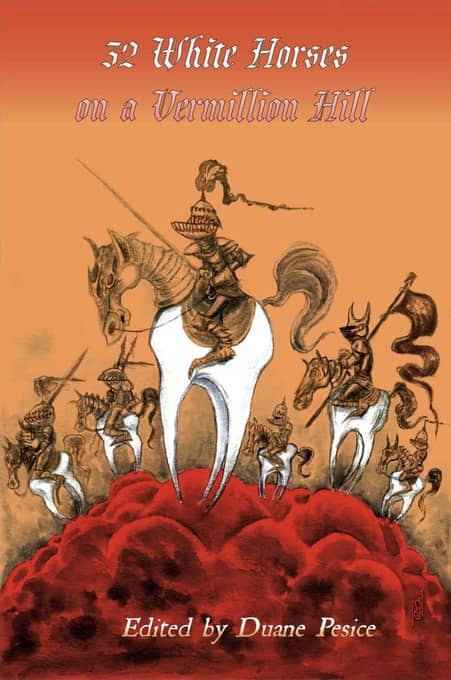

Reading for a Good Cause: 32 White Horses on a Vermillion Hill edited by Duane Pesice

|

|

I’ve heard from several readers about a new charity anthology benefiting horror writer Christopher Ropes, 32 White Horses on a Vermillion Hill. Most recently Robert Adam Gilmour wrote, saying:

There are no shortage of writers going through difficult times and I imagine you might get quite a number of emails for funding them but this involves two anthologies and some writers you are familiar with. His situation is horrifying enough that it has stuck in my head and I just wanted to see if you’d feature it on Black Gate.

I’m informed about a lot of worthy fundraising efforts every year, but Robert is right — this one is of particular interest, as it involves dozens of writers of keen interest to Black Gate readers. Editor Duane Pesice has assembled two volumes of 32 White Horses on a Vermillion Hill, both of which contain 32 stories & poems generously donated from members of the weird fiction & horror communities, including Jonathan Maberry, Michael Wehunt, Ashley Dioses, K.A. Opperman, Marguerite Reed, Jon Padgett, Douglas Draa, John Linwood Grant, Jeffrey Thomas, Jason A. Wyckoff, Frank Coffman, and many others. All the profits from the books go towards helping Christopher cover the costs of some long-needed dental work (see the Go-Fund-Me page here).

Christopher’s work has been published in Vastarien (Grimscribe Press), Nightscript (Chthonic Matter), Ravenwood Quarterly (Electric Pentacle Press), and other fine publications, and it’s clear he has a lot of friends in the industry. If you’re active in fandom or on social media, you doubtless encounter calls for help on a regular basis. But I’ve never seen one quite like this. Pesice has assembled two anthologies that would look impressive under any circumstances. Copies are available at Amazon and directly from Planet X Publications. If you’re going to read some horror this month, why not read for a good cause?