Only Disconnect: Ray Bradbury’s “The Murderer”

High on the list of unwritten books that I’d like to read is An Encyclopedia of Misconceptions. I am unswervingly committed to traditional paper books, but this is one that I would have to read electronically; a physical book would just be too damn big. Everyone would have a chapter — men, women, LBGTQ folks, atheists, evangelicals, millennials, seniors, Democrats, Republicans, police officers, bus drivers, food service workers, Fortune 500 CEO’s, any racial or sexual or religious or social or political or generational or economic group that you can name, in fact — everyone feels misunderstood. Everyone knows themselves to be quite different from what other people assume them to be.

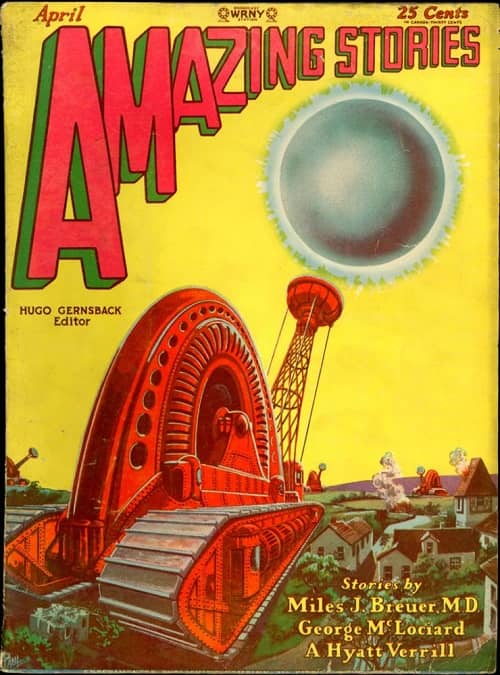

Such wrong ideas can attach themselves to almost everything in our lives, even including the books that we read. For example, one widespread misconception holds that the main purpose of science fiction is to predict the future! This notion is most rigidly held by those who have almost no familiarity with any actual science fiction. Such people gleefully point out SF’s failure to predict the internet (even though… well, we’ll get to that), or they “prove” the shallowness or silliness of the entire genre with the help of tales from the yellowing pages of Amazing Stories, yarns that depict a 21st century where everyone enjoys lives of anti-gravity-belt enhanced leisure with every want met by humanoid robot laborers (which hasn’t quite happened, in case you haven’t noticed).

But of course H.G. Wells didn’t really think that we were going to be invaded by Martians or believe that it was possible to concoct a formula that would make us invisible, nor was he convinced that vivisection could make the family dog into something that was virtually human. His books were really comments on the present in the form of visions of the future, and the technologies he invented were tools that enabled him to bring his own society and its potentialities into sharper focus.