Fantasia 2019, Day 8, Part 3: Knives and Skin

My last film of July 18 was in the big Hall Theatre. Knives and Skin was written and directed by Jennifer Reeder, and begins as a girl dies a violent death in a small midwestern town. In the wake of her disappearance secrets begin to come to light, and tensions rise among both her classmates and the adults. The movie proceeds to explore the town and its inhabitants in a series of sometimes-linked vignettes.

My last film of July 18 was in the big Hall Theatre. Knives and Skin was written and directed by Jennifer Reeder, and begins as a girl dies a violent death in a small midwestern town. In the wake of her disappearance secrets begin to come to light, and tensions rise among both her classmates and the adults. The movie proceeds to explore the town and its inhabitants in a series of sometimes-linked vignettes.

I have to say up front that I had a wildly different reaction to this film than the rest of the theatre did. The crowd was, by and large, audibly positive. This is a movie that has clear feminist principles, and is very direct about putting them on the screen. To judge not just from the reaction during the screening but the question-and-answer period after, many viewers responded to that, and good for them. Personally I didn’t care for the movie. I am going to explain why, but it’s important to note that this is a film that has the potential to work much better for people who are not me.

At its core, I felt that the dramatic structure of the film did not work. The various scenes did not seem to work as an ensemble, and individual characters did not have stories that felt fully developed. Much of the more interesting events that did happen had no obvious connection with the disappearance and death of Carolyn Harper (Raven Whitley). The movie felt to me like a series of short films, or ideas for short films, that did not cohere.

For example, near the end of the film the high schoolers who we’ve more-or-less followed through the film hear that one of their friends is on top of the school and might be about to jump. A group of a half-dozen or so teens gather out front of the school. It turns out that the youth on the roof isn’t going to jump, he just liked the view because it’s one of the few places he could see the road out of town. This is a problem for a number of reasons, but the first one is that a longing to get out of the town has not really been touched on or explored earlier in the film. It’s a perfectly credible motivation, but with no set-up or development it feels oddly gratuitous.

Then you wonder why, if this young man liked looking at the road out of town, nobody noticed the youth going up to the roof on any previous occasion. This brings up another problem: this town does not feel like a community of people who’ve known each other all their lives. People are too easily surprised by each other, or know too little about each other.

Before my second film of July 18, a surreal science-fiction movie from the director of

Before my second film of July 18, a surreal science-fiction movie from the director of

July 17 for me was a day of rest and running errands; then for my first film at Fantasia on July 18 I went to the De Sève Theatre to watch Maggie (메기). Directed by Yi Ok-seop from a film she wrote with star Koo Kyo-hwan, it’s the story of Yeo Yoon-young (Lee Ju-young), and her boyfriend Sung-won (Koo). Yoon-young’s a nurse at Love of Maria Hospital in Seoul. One day, an X-ray surfaces showing a man and a woman having sex in the X-ray room. The next day almost nobody comes in to work; the X-ray room’s a popular site for assignations, and everyone thinks they’re one of the figures in the X-ray. Yoon-young’s the only one who dares show her face, along with Doctor Lee (Moon So-ri). They end up forming an unlikely partnership as Maggie helps Lee learn to trust other people. Meanwhile, Sung-won finds work filling in sinkholes opening up in Korea, following an earthquake predicted by a catfish named Maggie — who also turns out to play an important role within the film.

July 17 for me was a day of rest and running errands; then for my first film at Fantasia on July 18 I went to the De Sève Theatre to watch Maggie (메기). Directed by Yi Ok-seop from a film she wrote with star Koo Kyo-hwan, it’s the story of Yeo Yoon-young (Lee Ju-young), and her boyfriend Sung-won (Koo). Yoon-young’s a nurse at Love of Maria Hospital in Seoul. One day, an X-ray surfaces showing a man and a woman having sex in the X-ray room. The next day almost nobody comes in to work; the X-ray room’s a popular site for assignations, and everyone thinks they’re one of the figures in the X-ray. Yoon-young’s the only one who dares show her face, along with Doctor Lee (Moon So-ri). They end up forming an unlikely partnership as Maggie helps Lee learn to trust other people. Meanwhile, Sung-won finds work filling in sinkholes opening up in Korea, following an earthquake predicted by a catfish named Maggie — who also turns out to play an important role within the film.

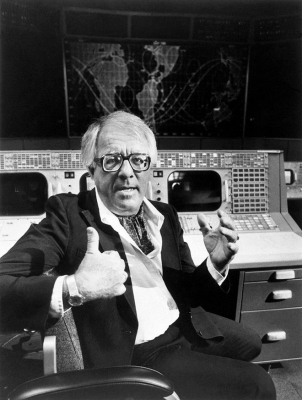

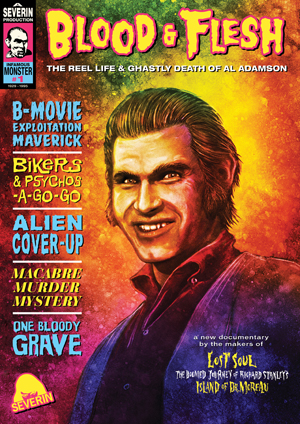

I expected my last film of July 16 would be a documentary called Blood & Flesh – The Reel Life and Ghastly Death of Al Adamson. You may not have heard of Adamson. I hadn’t. He was an exploitation filmmaker in the 1960s and 70s, responsible for titles like Satan’s Sadists, The Naughty Stewardesses, and Dracula Vs. Frankenstein, as well as not one but two separate films titled Psycho a Go-Go (Technically, one was Psycho à Go-Go; note accent). Introducing the documentary, Fantasia co-Director Mitch Davis described Adamson as more of a hustler than a filmmaker, then called up director David Gregory to briefly explain the film’s genesis. Gregory said it began as a special feature for a Blu-ray release, but the more he investigated Adamson, the more he realised the material was worth digging into more deeply. Thus, it’s now a feature, covering Adamson’s life, the films he made, and his awful death.

I expected my last film of July 16 would be a documentary called Blood & Flesh – The Reel Life and Ghastly Death of Al Adamson. You may not have heard of Adamson. I hadn’t. He was an exploitation filmmaker in the 1960s and 70s, responsible for titles like Satan’s Sadists, The Naughty Stewardesses, and Dracula Vs. Frankenstein, as well as not one but two separate films titled Psycho a Go-Go (Technically, one was Psycho à Go-Go; note accent). Introducing the documentary, Fantasia co-Director Mitch Davis described Adamson as more of a hustler than a filmmaker, then called up director David Gregory to briefly explain the film’s genesis. Gregory said it began as a special feature for a Blu-ray release, but the more he investigated Adamson, the more he realised the material was worth digging into more deeply. Thus, it’s now a feature, covering Adamson’s life, the films he made, and his awful death.