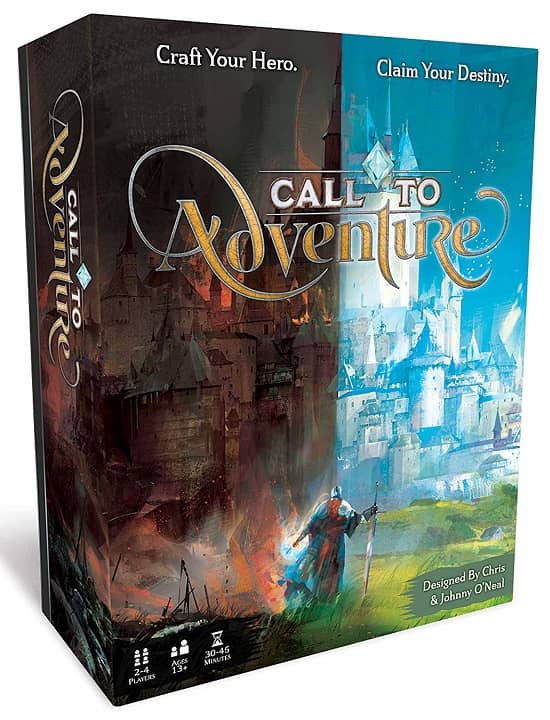

Create Your Character Backstory with Style: Call to Adventure from Brotherwise

I attended Gen Con for the first time in roughly fifteen years this year, and let me tell you, it was an experience. Wandering the massive Exhibit Hall — which quite literally took me three full days — drove home for the first time just how truly enormous the modern board game market is. 50,000 excited attendees packed the halls and pathways connecting over a thousand vendor booths, displaying thousands of new releases and tens of thousands of games. It was so packed it was sometimes impossible to move.

For a gamer whose very first gaming convention (CanGames in Ottawa in the late 70s) had maybe 250 attendees, it was a revelation. Fantasy gaming — like comics, role playing, and fantasy films — has gone mainstream in a big way. The tiny hobby I was once a part of is now a multibillion dollar business. Fantasy and Science Fiction were the dominant genres, but there were plenty of family games, wargames, and strange unclassifiable titles.

But it’s still about the games. I realized early that it would be impossible to take in every new title of interest, so instead I started at one end of the Exhibit Hall, taking pictures with my iPhone. I made my way methodically up and down each aisle until I arrived, three days and many hundreds of photos later, at the far end, with a record of every new game of interest. I can’t cover them all of course, but I can discuss a few here on the blog. And I’ll start with one of the first games I ordered as soon as I returned from Indianapolis: Call to Adventure from Brotherwise Games.