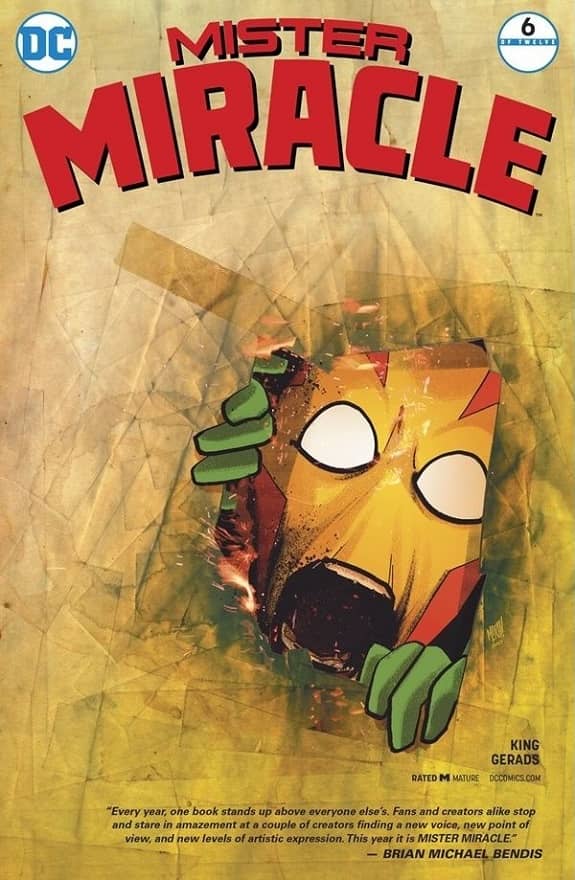

Absolutely Spectacular: Mister Miracle by Tom King and Mitch Gerads

So my ongoing quest to read as many of the classic comics has covered a lot of ground. I read and blogged about The Immortal Hulk. I covered Image’s Lazarus. Two weeks ago I blogged about Tom King and Gabriel Hernandez Walta’s Vision. A while ago I talked about a significant chunk of Kirby’s Fourth World. The last two bring me to DC’s 2017 series Mister Miracle by Tom King and Mitch Gerads.

In addition to Marvel’s Vision, Tom King has previously written DC’s Omega Men, co-written DC’s Grayson, and Vertigo’s Sheriff of Babylon. His striving for the artistic in comics, and his admiration for Alan Moore are both well-known and he seems to swing for the fences on every outing. That kind of innovation will come with some misses. I know a lot of fans didn’t respond well to King’s Batman or Heroes in Crisis. His natural medium seems to be the maxi-series starring characters who aren’t central to their fictional universes. In Mister Miracle, he and Gerads hit a home run, the kind that netted them four Eisners, a Hugo nomination, and big sales.