Vintage Treasures: City of Pearl by Karen Traviss

|

|

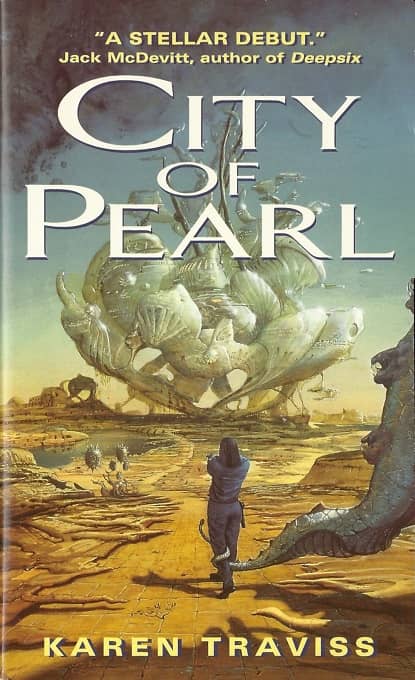

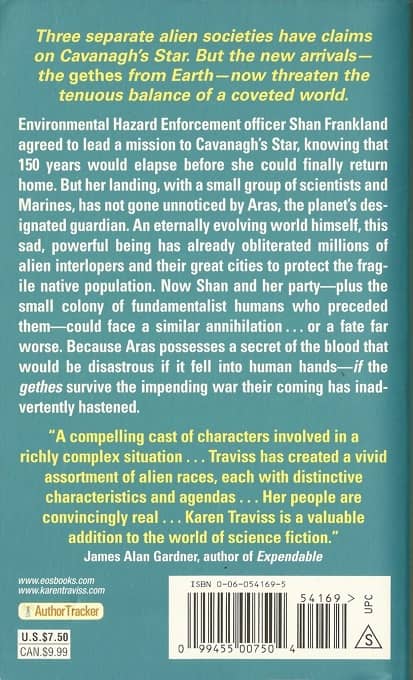

Cover by Greg Bridges

Karen Traviss’s debut novel City of Pearl was a big hit here in the Black Gate offices, and it was passed around repeatedly and excitedly. We were far from the only ones who liked it — it was shortlisted for both the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel and the Philip K. Dick Award, and came in third in the 2005 Locus poll for Best First Novel. It launched her career quite effectively, and it eventually became the opening novel in the 6-volume Wess’har Wars series.

City of Pearl tells the ambitious tale of the clash of several distinct alien civilizations near Cavanagh’s Star in the year 2299. In his review of the novel and its sequel Crossing the Line at SF Site, Stuart Carter wrote:

This isn’t hard SF by any means. Although the laws of physics are largely obeyed they’re not particularly important to the story; there’s no arousing military- or techno-porn, and precious little ‘common-sense’ machismo or gung-ho soldiering. It’s worth mentioning that there are philosophical similarities with The Dispossessed, but these books are, in my opinion, even deeper and more complex than Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic, and they’re still far from over.

Another glorious aspect of these two books is that they’re almost the antithesis of everything Trek: humans haring round the universe imposing their morality and point-of-view upon anyone who can listen, and always, eventually, turning out to be right, or at least admirable. And if we’re not even admirable then at least we have bigger guns than everyone else to console ourselves with. In Karen Traviss’s universe we’re seen as being far from admirable and even further from right, and it looks like being a very hard, possibly even fatal, lesson for us to learn… If you want to read something that will leave you thinking, perhaps if you’re a fan of Ursula K. Le Guin, Kim Stanley Robinson or, more generally, of intricately gloomy English science fiction, then this series is one you want to read — I promise.

City of Pearl didn’t just hit with the critics. It is still in print, 15 years long after it was originally published; an extraordinary feat by any measure. Here’s the complete list of all six novels in the series.