Fantasia 2019, Day 17, Part 2: The Relative Worlds

For my second film of July 27 I stuck around the Hall Theatre for another animated feature, this time from Japan. Preceding it was a 13-minute animated short from Canada.

For my second film of July 27 I stuck around the Hall Theatre for another animated feature, this time from Japan. Preceding it was a 13-minute animated short from Canada.

“Alexis Inside” was directed by Montrealer Brandon Blommaert. Alexis is one of a group of friends who play a VR video game. When one of the friends goes missing, the vampire-like force that afflicted her is passed on to Alexis, who shuts herself away from the world. Can her remaining friend save her? The short’s open to interpretation, and has a stylish look based on old-style computer graphics given modern details and animation. I read it as being about depression, and see an ambiguity in the title having to do with the insides of Alexis, as opposed to Alexis choosing to lock herself away from the world. The film’s an interesting, disconcerting piece, somewhat alienating due to its look but ultimately emotionally engaging.

The feature I’d come to see was The Relative Worlds (Sotai Sekai, ソウタイセカイ). Written and directed by Yuhei Sakuragi, it’s adapted from a series Sakuragi did for Hulu Japan. Shin (Yuki Kaji) is a Japanese teenager whose mother died a sudden inexplicable death when he was a child, part of an ongoing wave of inexplicable deaths across Japan. His date with Kotori (Maaya Uchida) is interrupted by the death of his father, which we in the audience see is connected with something far stranger. It turns out that Japan is linked to another reality, where history took a very different turn. Everyone in Shin’s reality — or at least Shin’s Japan — has a doppelganger there, and when somebody in one reality dies so does their doppelganger in the other. Shin’s double, Jin, has crossed over to this reality to kill Kotori, because in Jin’s reality Kotori’s double is the despotic Princess Kotoko, who rules the dystopia of that world and also has dark schemes for this one.

This is not a bad plot, and the deaths of Shin’s parents are unsurprisingly tied in with the core plot of the conflict of the two worlds. There’s a solid emotional background, in other words. The problem is the rest of the story. It’s uninvolving, playing out on a small scale. This does change in the last third or so of the film, as the other world deploys the full strength of its forces, and organisations in this world get involved. But the build’s erratic, too slow for too long.

What I think the movie is trying to do is keep the story focussed on the teen protagonists, Shin and Jin and Kotori, and that’s not a bad idea. But there’s an asymmetry. The bad guys from the otherworld are too powerful to stop. You understand why Jin planned to kill Kotori, and the movie doesn’t really come up with a better alternative. Nor does it effectively explore the morality of killing an innocent for the greater good, partly because the science fiction aspect of the story is so outlandish, and partly because the greater good is abstract. The movie doesn’t really dramatise either world; doesn’t make us believe in a society of individuals in either reality.

Saturday, July 27, was going to be a long day for me at Fantasia. Hopefully a good one, too. I had five movies on my schedule, starting at noon with the animated Chinese fantasy-adventure White Snake (白蛇:缘起, 白蛇:緣起).

Saturday, July 27, was going to be a long day for me at Fantasia. Hopefully a good one, too. I had five movies on my schedule, starting at noon with the animated Chinese fantasy-adventure White Snake (白蛇:缘起, 白蛇:緣起).

My second film of July 26 was in the big Hall theatre, a science-fiction anime called Human Lost (人間失格). Directed by Fuminori Kizaki, it was scripted by Tou Ubukata based on a novel by Osamu Dazai. The movie’s set in 2036, when advanced nanotechnology has given human beings a lifespan of 120 years but turned Japan into a deeply unequal society, with the wealthy sequestered inside a vast citadel called “the Inside.” Some people, for unclear reasons, metamorphose into monsters: the ‘Human Lost’ phenomenon. A troubled young artist, Yozo Oba (Mamoru Miyano), gets involved with his cyborg friend Takeichi (Jun Fukuyama) when he attempts to break into the Inside, and sets off a complex series of events which bring to light the truth about the Human Lost problem and the future of 2036 — but which also might drive Yozo over the edge of sanity.

My second film of July 26 was in the big Hall theatre, a science-fiction anime called Human Lost (人間失格). Directed by Fuminori Kizaki, it was scripted by Tou Ubukata based on a novel by Osamu Dazai. The movie’s set in 2036, when advanced nanotechnology has given human beings a lifespan of 120 years but turned Japan into a deeply unequal society, with the wealthy sequestered inside a vast citadel called “the Inside.” Some people, for unclear reasons, metamorphose into monsters: the ‘Human Lost’ phenomenon. A troubled young artist, Yozo Oba (Mamoru Miyano), gets involved with his cyborg friend Takeichi (Jun Fukuyama) when he attempts to break into the Inside, and sets off a complex series of events which bring to light the truth about the Human Lost problem and the future of 2036 — but which also might drive Yozo over the edge of sanity.

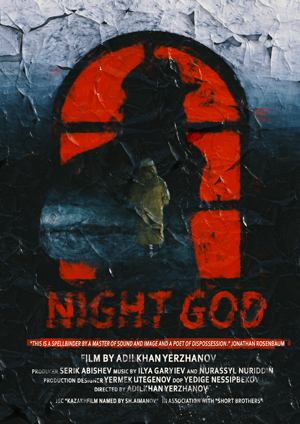

My first film on Friday, July 26, was a Kazakh work playing at the de Sève Cinema. Written and directed by Adilkhan Yerzhanov, Night God is a particular sort of uncompromising. It’s a beautiful picture, but extremely slow, still, and self-consciously meditative. I was deeply moved, for all its studied avoidance of simple dramatic action.

My first film on Friday, July 26, was a Kazakh work playing at the de Sève Cinema. Written and directed by Adilkhan Yerzhanov, Night God is a particular sort of uncompromising. It’s a beautiful picture, but extremely slow, still, and self-consciously meditative. I was deeply moved, for all its studied avoidance of simple dramatic action.