Magical Odes and Mysterious Trilogies: The Poet King by Ilana C. Myer

|

|

|

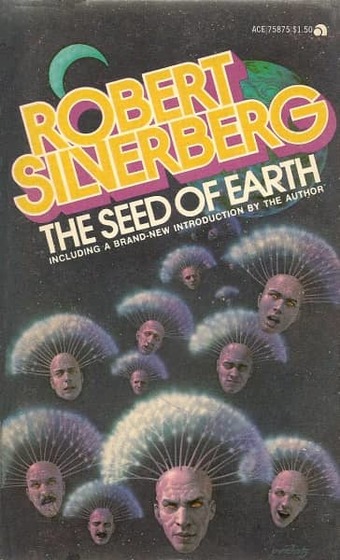

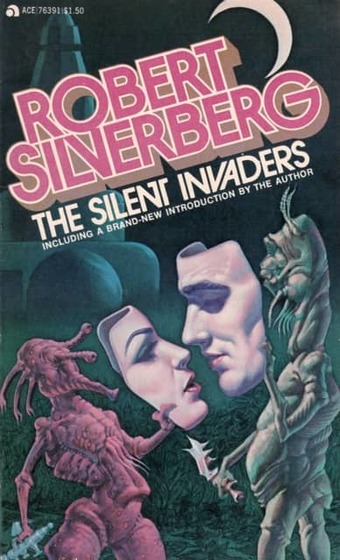

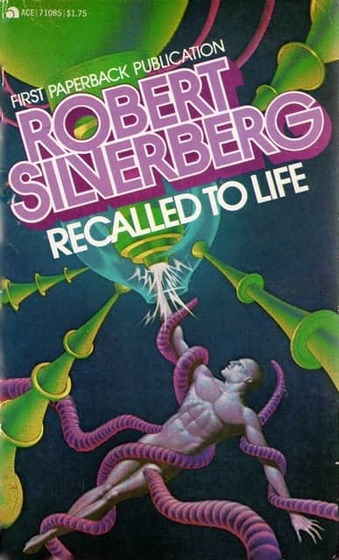

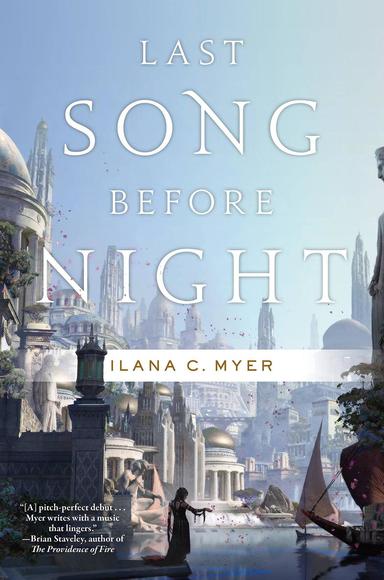

Covers by Stephan Martiniere

Every time a fantasy trilogy wraps up, we bake a cake in the Black Gate offices. (As you can imagine, our diet consists of a lot of cake. Man, we need a gym.)

Ilana C. Myer’s new novel The Poet King brings to a close the trilogy that began with Last Song Before Night. One of the reasons I love this series is all the mystery. Like, what’s the trilogy called, exactly? Amazon refers to it as the Tower of the Winds series. Unless you’re buying the Kindle version, in which case it’s called The Harp and Ring Sequence. The Internet Science Fiction database clears the issue right up by calling it, definitively, Last Song Before Night / The Harp and the Ring, and then listing all the books in the wrong order.

Well, no one said the life of a science fiction book blogger would be easy. Let’s move on the the Publishers Weekly review, because at least that’s straightforward. Hopefully. Here’s an excerpt; you can judge for yourself.

Myer concludes the Harp and Ring Sequence (after Fire Dance) with this opulent, ambitious fantasy. Political upheaval in Kahishi leads to Elissan Diar declaring himself the land’s first Poet King, capable of weaving magic into his odes. Embittered Lady Rianna Gelvan plots to kill Elissan before he takes the throne… Myer’s intricately braided plot strands culminate in a clash of supernatural Otherworld powers. Those new to the series will have no trouble connecting with the well-drawn protagonists but may struggle to untangle the history of this rich universe which draws from a welter of world mythologies. Still, readers will be blown away by the lush, lyrical prose and epic scale of this novel.

We covered the previous books in the series here and here. The Poet King was published by Tor Books on March 24, 2020. It is 320 pages, priced at $29.99 in hardcover and $14.99 in digital formats. The cover is by Stephan Martiniere. Read Howard Andrew Jones’ feature interview with Ilana here.

See all our coverage of the best new fantasy series here.