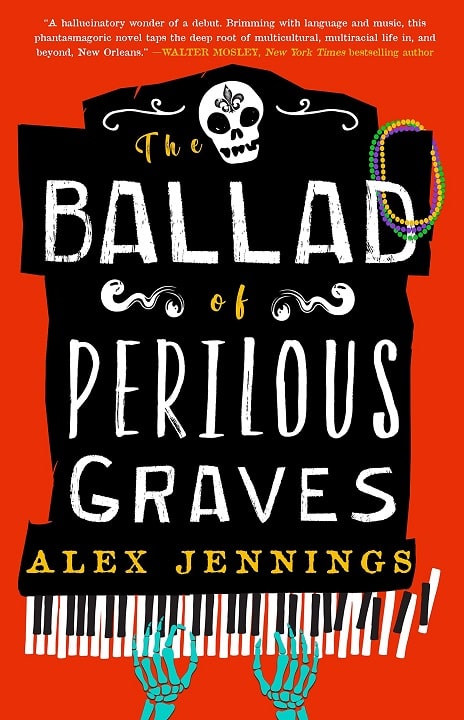

New Treasures: The Ballad of Perilous Graves by Alex Jennings

The Ballad of Perilous Graves (Redhook, June 21, 2022)

What’s the best thing about knowing writers on Facebook? They’re always talking about books, that’s what. Yesterday P. Djèlí Clark (A Master of Djinn, The Haunting of Tram Car 015) tipped me off to a great new debut fantasy by Alex Jennings.

The Ballad of Perilous Graves by Alex Jennings — featuring a New Orleans of sky trolleys, living graffiti, trans dimensional portals, and terrifying haints — gotta be one of the most amazing books I’ve read in a minute. Magical, lyrical, gritty, otherworldly… sh*t is hype like Bayou Classic in the 90s, set to song. Put this on your list for the summer.

Okay, that doesn’t tell you much about the plot. Social media ain’t perfect. Besides, we’re Black Gate, we have a staff of investigative reporters for that.