Essential Short Fiction

Sf Signal has an interesting discussion going on.

Sf Signal has an interesting discussion going on.

Once again, the gaps in my own reading are extensive.

Sf Signal has an interesting discussion going on.

Sf Signal has an interesting discussion going on.

Once again, the gaps in my own reading are extensive.

Over at Grognardia, James Maliszewski has posted a retrospective review of one of my favorite RPG relics, Oracle Game’s Alma Mater, the role playing game of high school life in the 1970s.

Over at Grognardia, James Maliszewski has posted a retrospective review of one of my favorite RPG relics, Oracle Game’s Alma Mater, the role playing game of high school life in the 1970s.

And I do mean relic. I collect role playing games and, after nearly two decades of fruitless searching, I finally gave up and paid an outrageous sum for an unused copy on eBay a few years ago. It was the last significant RPG title from the era I didn’t own.

It was worth it. Alma Mater was notorious when it was released in 1982, and it retained much of that notoriety through the years. It was banned from Gencon by TSR, and well-known artist and editor Liz Danforth wrote a famously scathing editorial in Sorcerers Apprentice magazine attacking the game.

Today though, Alma Mater is chiefly remembered for its artwork, by old-school TSR artist Erol Otus (who did the classic cover for Deities & Demigods, and interior artwork for the AD&D Monster Manual, among many others). The content of the game itself, as you’d doubtless expect, is fairly tame by modern standards, but the artwork can still raise eyebrows. You can see much of it collected at the Cyclopeatron blog.

I’ve never played the game. Not a lot of people did, as a matter of fact — it quickly vanished, despite (or perhaps because of) all the publicity. Hence its relatively scarcity today, and the delight it still brings to bloodless eBay vulture sellers, may they suffer a thousand deaths.

I’m not sure why more game companies didn’t stumble on this idea — it seems completely natural to me now. Let’s be honest; not much scares me any more. My senior biology teacher, Ms. Bray? She still scares me.

I’ve always been most terrified by the stuff I’ve never even seen. I’ve screamed my way through ghost hunting expeditions having never once actually laid eyes on an apparition of any kind. Jaws is one of my favorite movies, mainly for the scenes when you know the shark is somewhere just outside your line of sight, and I have read books that have made me afraid to have any part of me not under the covers once I’m in bed, for days on end.

I’ve always been most terrified by the stuff I’ve never even seen. I’ve screamed my way through ghost hunting expeditions having never once actually laid eyes on an apparition of any kind. Jaws is one of my favorite movies, mainly for the scenes when you know the shark is somewhere just outside your line of sight, and I have read books that have made me afraid to have any part of me not under the covers once I’m in bed, for days on end.

It is universally true that what you imagine is exponentially more horrible than the reality, which is why hack-and-slash movies copiously strewn with limbs and drenched in bodily fluids have never done it for me.

It’s no surprise then, that I’ve recently become addicted to the “theater of the mind” known as classic radio.

Having repeatedly watched the movie A Christmas Story, where little Ralphie makes a bee-line to the enormous living room radio to listen to “Little Orphan Annie,” I was aware that radio serials predated television. But it wasn’t until channel surfing on my satellite radio one day that I stopped on a station, and hearing Peter Lorre’s voice, fell hopelessly in love.

No, not with Peter Lorre. I’ve been in love with him since reruns of “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” and “Tales of Terror.” What I fell in love with was an old time radio drama called The Inner Sanctum, and I had to know more.

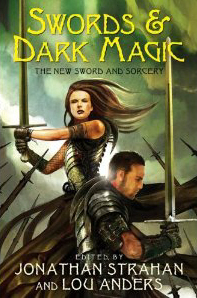

It isn’t often we see a new Sword & Sorcery anthology, especially one from a major publisher.

It isn’t often we see a new Sword & Sorcery anthology, especially one from a major publisher.

Swords & Dark Magic: The New Sword & Sorcery, edited by Jonathan Strahan & Lou Anders (Eos Books/Subterranean Press) is the first one to cross my desk in years and, with a new Elric tale by Michael Moorcock, a Black Company story by Glen Cook, a Majipoor piece from Robert Silverberg, a Cugel the Clever tale by Michael Shea, and contributions from Steven Erikson, James Enge, Joe Abercrombie, Tanith Lee, Garth Nix, C.J. Cherryh, Greg Keyes, Gene Wolfe, Tim Lebbon, Caitlín R. Kiernan, and many others, it looks like the real deal.

But do Strahan and Anders deliver real Sword & Sorcery, or just a close approximation?

To answer that we recruited Jason M. Waltz, publisher of Rogue Blades Entertainment, editor of the acclaimed anthologies Rage of the Behemoth and Return of the Sword, and true expert in heroic adventure.

His 6,000-word analysis, liberally spiced with his own thoughts on the state of the genre, begins after the jump.

“The Weird of Ironspell” by John R. Fultz

Illustrations by Alex Sheikman

( CONCLUSION! )

8. The Breaking of the Weird

His name was a legend in every kingdom of Arboria although some scholars argued that he had never existed.

Ironspell was a myth, an allegory, a fireside yarn that grizzled storytellers traded for ale and roasted meat. Long after the War of Darkness had ended, long after the Death Plague was wiped from the continent, and decades after the fortress city of Neshma fell to northern barbarians, the hero’s name lingered. Sages and scribes wrote tales of his adventures in leather-bound tomes alongside fables, folk stories, and fanciful verse.

While the living world scoffed at Ironspell the Legend, Ironspell the Man roamed the barren and forsaken places of the earth. Like a restless ghost he walked over burning sands, climbed mountain passes, and roved the depths of tangled forests. He had grown old, yet still he carried a great silver sword on his back, and still he wore the tarnished mail of a knight from the Royal House of Neshma. His hair and beard had gone from raven black to snowy white, and the brightness of his green eyes had faded to steely gray, the color of a cherished grief.

Last week, our esteemed editor John O’Neill posted a wonderful reminiscence of one of the key science-fiction anthologies of the 1970s: Isaac Asimov’s Before the Golden Age. This hefty volume (sometimes divided over three paperbacks) is an intriguing mixture of autobiography, literary analysis, and miles o’ great pre-Campbellian magazine science fiction. Before the Golden Age is a classic piece of early pulp archaeology.

Last week, our esteemed editor John O’Neill posted a wonderful reminiscence of one of the key science-fiction anthologies of the 1970s: Isaac Asimov’s Before the Golden Age. This hefty volume (sometimes divided over three paperbacks) is an intriguing mixture of autobiography, literary analysis, and miles o’ great pre-Campbellian magazine science fiction. Before the Golden Age is a classic piece of early pulp archaeology.

O’Neill’s post specifically made me recall “Parasite Planet” by Stanley G. Weinbaum. I did not read this story for the first time in Before the Golden Age, but in The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum. This book, which contains an introduction from Isaac Asimov and an afterword by Robert Bloch, is the first of Del Rey’s many “The Best of . . .” collections, a series I credit with getting me interested in many of the classic science-fiction authors of the mid-twentieth century. I still own my yellowed copies of The Best of John W. Campbell, The Best of Jack Williamson, The Best of Leigh Brackett, The Best of C. L. Moore, The Best of L. Sprague De Camp, and The Worst of Jefferson Airplane. (Wait, one of these things is not like the other. . . .)

I first read “Parasite Planet” in The Best of Stanley G. Weinbaum, but the Del Rey edition was not my initial encounter with Mr. Weinbaum. That came through another of the great anthologies of the ‘70s (wow, I am really hitting “great anthologies” in a big way in this post), The Science Fiction Hall of Fame. Weinbaum’s 1934 classic, “A Martian Odyssey,” was the first story in the collection, and also its oldest. The vote of the Science Fiction Writers of America that determined the contents of the collection picked the story as the second best SF short piece ever published, with only Asimov’s “Nightfall” besting it. “A Martian Odyssey” floored me when I first read it at age eighteen, and so I had to find out more about this Weinbaum guy who seemed to have vanished, since he was one of the few authors in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame whom I did not recognize from later achievements.

There turned out to be, unfortunately, a tragic reason for this. Weinbaum burst onto the SF scene with “A Martian Odyssey,” which was his first sale. He was immediately the most popular author in the field; everybody loved his work. Eighteen months later, in December 1935, Weinbaum was dead from lung cancer at age thirty-three.

Graham McNeill’s novel Empire: The Legend of Sigmar (Black Library) is this year’s winner of the David Gemmell Legend Award for Best Fantasy Novel of 2009.

Graham McNeill’s novel Empire: The Legend of Sigmar (Black Library) is this year’s winner of the David Gemmell Legend Award for Best Fantasy Novel of 2009.

The list of nominees, including Brandon Sanderson, Joe Abercrombie, and Robert Jordan, was announced April 7.

The David Gemmell Legend Award is a fan-voted award administered by the DGLA. The Legend Award for Best Fantasy Novel was first granted in 2009, to Andrzej Sapkowski’s Blood of Elves.

As winner, McNeill received a replica of the mighty Snaga, the axe wielded by Druss in David Gemmell’s novel Legend.

I think George Mann, publisher of Black Library, captured my thoughts nicely when he said:

‘We are delighted for Graham – not only is this a wonderful acknowledgement of a fine writer, but it is an important victory for franchise fiction, which is often overlooked by the wider genre community.’

The Ravensheart Award, for best Fantasy Book Jacket/artist, went to Best Served Cold – art and design by Didier Graffet, Dave Senior and Laura Brett.

The Morningstar Award for Best Fantasy Newcomer/debut went to Pierre Pevel’s The Cardinal’s Blades.

Black Library editor Nick Kyme has a lengthy blog entry on the awards ceremony here.

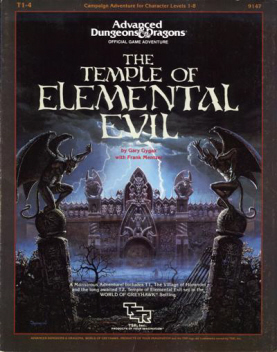

Role-playing games have always interested me because, at heart, they’re about stories. They’re ways to tell stories that you don’t know in advance, ways to bring people together to create something unpredictable but still structured in a narrative form. Now, that said, the question is: how do you go about doing that? If you’re writing a module, an adventure, that referees are going to pick up off a store shelf (or download from a web site), what do you give them to help create that story with their players?

Role-playing games have always interested me because, at heart, they’re about stories. They’re ways to tell stories that you don’t know in advance, ways to bring people together to create something unpredictable but still structured in a narrative form. Now, that said, the question is: how do you go about doing that? If you’re writing a module, an adventure, that referees are going to pick up off a store shelf (or download from a web site), what do you give them to help create that story with their players?

The traditional first edition Dungeons & Dragons answer to this was: you give them a dungeon. You give them a sandbox, an area to explore filled with monsters and treasure, and maybe a few adventure hooks. What will the players do with it? Who knows?

For a long time, probably starting in the mid-80s at about the point where I started seriously playing D&D, this approach was in disrepute. A dungeon with a bunch of monsters isn’t a story, the argument ran. A story should have a structure, and ideally different moods, maybe even different settings. It should end in a different place than it began. You could see this philosophy settle in at TSR with the Dragonlance series of modules, taking firmer hold with second edition D&D.

Nowadays, though, at least a few people are beginning to swing back to the first approach. Structuring stories out ahead of time kills the spontaneity of the game, one might argue. Let the players and referee develop the story at the table, not by going through the motions worked out ahead of time by some designer. Don’t railroad the players; give them the situation, and see what they do on their own. (I’m vastly simplifying all these positions, and only presenting some of the arguments. I think I’m getting at the essence, though.)

I’ve come around to that last argument. I want to explain why, because I’ve recently wrapped up a First Edition game in which I was fascinated to see a story I never anticipated arise out of a module that features little in the way of pre-structured narrative: The Temple of Elemental Evil by Gary Gygax and Frank Mentzer (TSR, 1985).

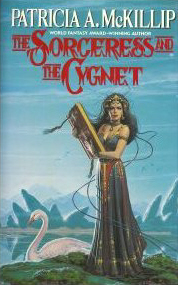

Corleu is an oddity, a white-haired youth in a black-haired tribe of wanderers. His family has a talent for foresight, but all he has is a knack for stories. And then one year the tribe goes south for the winter and finds itself in a marsh where time seems to stand still, where the flowers are perfect but the skies are invisible behind the mists — and no one knows how long they’ve been there. No one but Corleu notices anything wrong.

Corleu is an oddity, a white-haired youth in a black-haired tribe of wanderers. His family has a talent for foresight, but all he has is a knack for stories. And then one year the tribe goes south for the winter and finds itself in a marsh where time seems to stand still, where the flowers are perfect but the skies are invisible behind the mists — and no one knows how long they’ve been there. No one but Corleu notices anything wrong.

Then things get really surreal.

If you like your magic as a form of exotic science, with clearly delineated cause and effect — the sort of worldbuilding Brandon Sanderson does, for instance — The Sorceress and the Cygnet is probably not the book for you. Little is explained, least of all the magic system.

The plot revolves around five beings whose nature is never entirely defined. They could be gods, although they’re never worshipped. They could be stories come to life. They have titles rather than names. They’re represented in the heraldry and the constellations.

They seem extremely powerful, but four of them have apparently been trapped by the fifth, the being called the Cygnet. One of those four — the Gold King, who reads like a sun god or a death god or both — tricks Corleu into a quest to find the Cygnet’s heart.

Luke Forney. who reviewed Black Gate 13 last year, digs into our latest issue with part one of a three-part review:

Luke Forney. who reviewed Black Gate 13 last year, digs into our latest issue with part one of a three-part review:

You would be hard-pressed to find a fantasy magazine out there better than Black Gate. It is a solid magazine with good content, and very much worth the entry fee. Issue 14… is a behemoth. Gigantic doesn’t begin to describe it.

Just as he was last issue, Luke is taken with the latest adventures of Brand the Viking in “The Bonestealer’s Mirror” by John C. Hocking:

Brand the Viking, along with his companions, stop to investigate a signal fire, only to find a town beset by a terrible creature that steals the bones from its victims’ bodies. Hocking proves, yet again, to be a top-notch storyteller worthy of the mantle of the next Robert E. Howard, yet he fills his tales with a sterling originality that would be done a gross disservice by labeling it anything other than purely Hocking. The plot, the characters, the setting: all are wonderful, and a joy to explore. The day a collection of Hocking’s Brand stories comes out is the day I wait in line to buy a copy.

As well as “The Word of Azrael” by Matthew David Surridge:

This tale of a man on a lifelong quest in search of the angel of death grasps the moody, mystical quality of both dream and myth, and weaves it throughout. The story carries you along without effort, and is certainly wonderful to read.

And Rich Horton’s lengthy non-fiction piece “Back to the Future: Modern Reprints of Classic Fantasy”:

A wonderful essay from a man entrenched in the genre, Horton explores host of publishers who are bringing back some unjustly forgotten classics. While most will be familiar with some of these, few will be familiar with all, and the essay brings up both authors and books that I will be keeping an eye out for. A wonderful essay.

You can find Part One of the complete review here.