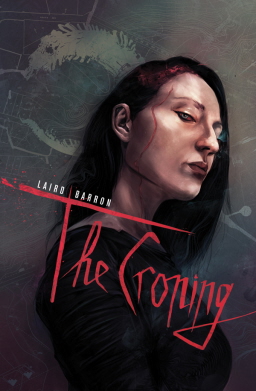

New Treasures: Laird Barron’s The Croning

Howard and I first met the talented Laird Barron at the World Fantasy Convention in Austin, Texas in 2006. At the time he’d published only a handful of short stories in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, SCI FICTION and a few other markets — but what great stories they were, including”Hallucigenia,” “The Imago Sequence,” and “Shiva, Open Your Eye.”

Howard and I first met the talented Laird Barron at the World Fantasy Convention in Austin, Texas in 2006. At the time he’d published only a handful of short stories in The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, SCI FICTION and a few other markets — but what great stories they were, including”Hallucigenia,” “The Imago Sequence,” and “Shiva, Open Your Eye.”

Laird turned out to be a fascinating and entertaining guy. Seriously, next time you’re at a convention, hang with this guy. He has a pure, unabashed love of Lovecraft, pulp and crime fiction, and westerns, and his fiction combines these elements in marvelous new ways. And if you get a chance, ask him to explain his famous comment that the Bible is “the greatest horror story ever told.”

Laird’s first collection was The Imago Sequence & Other Stories, released in trade paperback by Night Shade Books in 2007; it was followed by Occultation in 2010 (also from Night Shade). He won the 2007 and 2010 Shirley Jackson Award for his collections, and has been nominated for numerous other awards, including the Crawford, Sturgeon, International Horror Guild, World Fantasy, Bram Stoker and Locus Awards. These two books helped cement his reputation, and transform him from a rising young star to one of the most respected dark fantasy and horror writers working today.

His long-awaited first novel, The Croning, arrived in May, and true to form it combines cosmic horror and noir fiction in Barron’s signature style:

Strange things exist on the periphery of our existence, haunting us from the darkness looming beyond our firelight. Black magic, weird cults and worse things loom in the shadows. The Children of Old Leech have been with us from time immemorial. And they love us. Donald Miller, geologist and academic, has walked along the edge of a chasm for most of his nearly eighty years, leading a charmed life between endearing absent-mindedness and sanity-shattering realization. Now, all things must converge. Donald will discover the dark secrets along the edges, unearthing savage truths about his wife Michelle, their adult twins, and all he knows and trusts. For Donald is about to stumble on the secret…of The Croning.

The Croning is 245 pages; it is available in hardcover (for $24.99) and digital ($8.99) format from Night Shade Books.

A few months ago, I started an irregular series of posts about Romanticism and fantasy. I wanted to talk about the significance of Romanticism, the literary movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, to the development of fantasy fiction. For a variety of reasons, I’d been distracted from continuing those posts for a while; I want to return to them now. The original inspiration for this series of posts came when

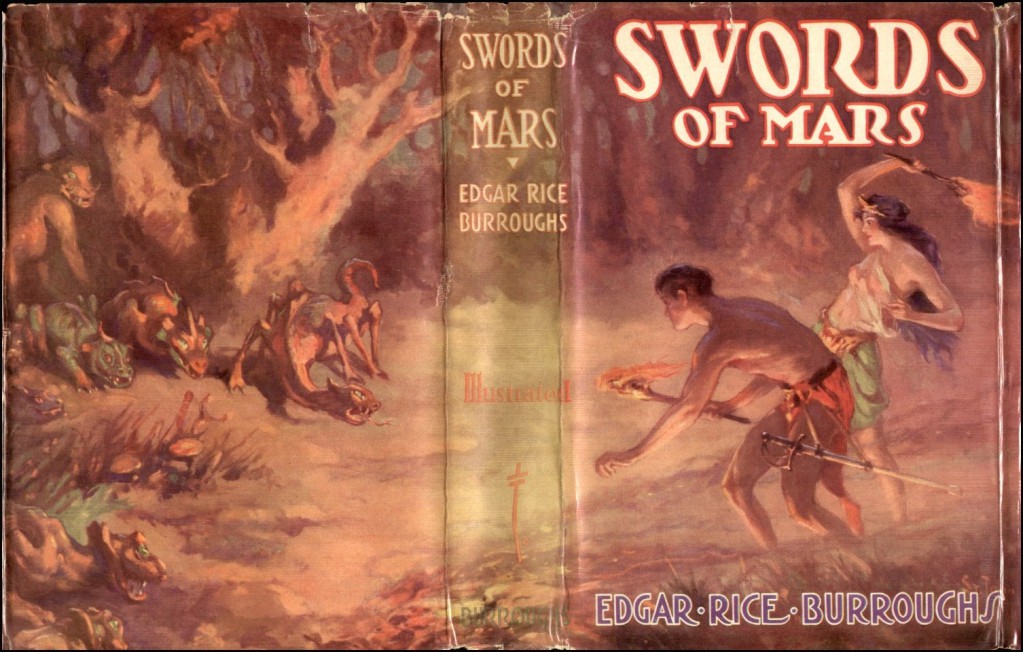

A few months ago, I started an irregular series of posts about Romanticism and fantasy. I wanted to talk about the significance of Romanticism, the literary movement of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century, to the development of fantasy fiction. For a variety of reasons, I’d been distracted from continuing those posts for a while; I want to return to them now. The original inspiration for this series of posts came when  “But my memories of that great tragedy are not all sad. There was high adventure, there was noble fighting; and in the end there was — but perhaps you would like to hear about it.”

“But my memories of that great tragedy are not all sad. There was high adventure, there was noble fighting; and in the end there was — but perhaps you would like to hear about it.”

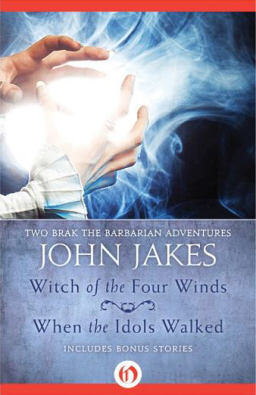

It’s a lot easier for me to be generous about other genres than it used to be. I’m trying to decide if that has something to do with me mellowing with age, or if it’s because there’s a whole lot more sword-and-sorcery available than there was ten years ago … or if it’s simply that I don’t feel shut out anymore now that I’m writing sword-and-sorcery stories for a living.

It’s a lot easier for me to be generous about other genres than it used to be. I’m trying to decide if that has something to do with me mellowing with age, or if it’s because there’s a whole lot more sword-and-sorcery available than there was ten years ago … or if it’s simply that I don’t feel shut out anymore now that I’m writing sword-and-sorcery stories for a living.

The July-August issue of Interzone features new stories by Sean McMullen (”Steamgothic”), Aliette de Bodard (”Ship’s Brother”), David Ira Cleary (”One Day in Time City”), Gareth L. Powell (“Railroad Angel”), and the 2011 James White Award-winning story “Invocation of the Lurker” by C.J. Paget; cover artwork by Ben Baldwin; an interview with Juliet E. Mckenna by Elaine Gallagher; “Ansible Link” genre news and miscellanea by David Langford; “Mutant Popcorn” film reviews by Nick Lowe; “Laser Fodder” DVD/Blu-Ray reviews by Tony Lee; and book reviews by various contributors.

The July-August issue of Interzone features new stories by Sean McMullen (”Steamgothic”), Aliette de Bodard (”Ship’s Brother”), David Ira Cleary (”One Day in Time City”), Gareth L. Powell (“Railroad Angel”), and the 2011 James White Award-winning story “Invocation of the Lurker” by C.J. Paget; cover artwork by Ben Baldwin; an interview with Juliet E. Mckenna by Elaine Gallagher; “Ansible Link” genre news and miscellanea by David Langford; “Mutant Popcorn” film reviews by Nick Lowe; “Laser Fodder” DVD/Blu-Ray reviews by Tony Lee; and book reviews by various contributors.