Lin Carter’s Imaginary Worlds #1 History of Fantasy

|

|

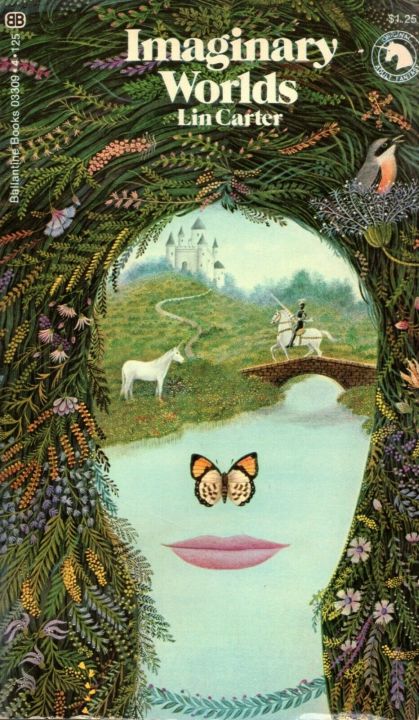

Imaginary Worlds (Ballantine Books, June 1973). Cover by Gervasio Gallardo

I’m the age Proust was when he died, and Lin Carter books are my Madeleine cake.

The covers transport me to the sunny afternoon garage sales of my teens. Picking up one — they’re tiny compared to today’s paperbacks — and riffling the yellowing pages, and I’m thirteen years old, on a hill-walking holiday in Wales, rummaging in a small town charity shop while the rain rattles the dirty glass window. And later, playing Dungeons and Dragons (AD&D was my edition!) in a stuffy teenage bedroom in a Victorian house where the hundred-year-old window slammed down and nearly took off the DM’s leg as he was smoking a roll-up while perched on the ledge…

And like the D&D games of my mid teens, Lin Carter’s books never quite lived up to the potential of the promised exoticism. In our case, we were teenagers with limited life experience. We did very well, as far as it went, and our DMs were patient and I argued too much. Lin Carter, several times married, a Korean war veteran — the Vietnam sequence that kicks off the Callisto books reads very authentically — cosmopolitan New Yorker, experienced editor, has less excuse.

There are good reasons for liking Lin Carter. He’s a master of the exotic. For all that he deals in stock types, he has an exhilarating freedom of invention, cheerfully mixing swords and nuclear powered sentient ships.

|

|

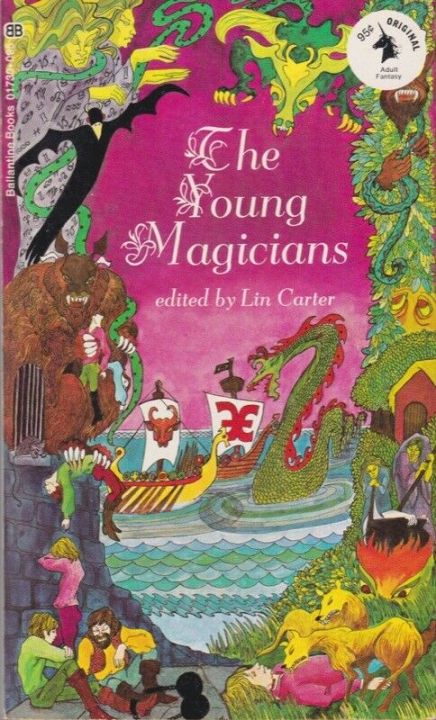

The Young Magicians (Ballantine Books, October 1969). Cover by Sheryl Slavitt

However, his books fall merely into the category of “nice comfort read”; they don’t quite take you into the exotic worlds he weaves. He prefers storytelling to drama — leans heavily on narrative summary — has neither dark undertow of Le Guin’s Wizard of Earthsea, nor the humor of Fritz Lieber’s Fafhrd and Grey Mouser tales. His touch is often light — he likes his cinematic and Olympian points of view — but with neither the archness of Vance nor the humor of Pratchett. His characters are larger than life, and yet strangely unmemorable, perhaps because he does not ground them Marvel-movie style in sweat and blood, which is odd for somebody that will at least have gone through basic infantry training.

Perhaps it’s because he so often strives for retro literary effects out of kilter with the grittier subject matter. I suspect he’s emulating the stylists of yore — Dunsany, Edison, and Cabal — who were themselves emulating styles of yore. The end result is Hendrix riffs played expertly, but on a harpsichord.

Wild Man Lin Carter

And, I wager, underlying all of that was that he was alternately overthinking and not thinking enough… because his most significant professional hat was that of editor and critic.

In truth, we still know who Carter was because he was supremely good at making anthologies of the good stuff. His The Young Magicians is where I first met Fafhrd and Grey Mouser, and his other anthologies sent me off to explore the sometimes turgid roots of the genre.

All this and more is why — on landing a contract to write a LitRPG — I went to my own heroic efforts to get hold of a copy of his Imaginary Worlds, a history of Fantasy as it stood in the early 1970s, plus his thoughts on worldbuilding. I was prompted in part by James McGlothlin’s excellent review of the book for Black Gate back in 2013.

I wanted to understand the thinking of this editor whose tastes influenced mine, and — without falling into the trap of emulating the emulator of emulators — learn how he created such exotic places. Unfortunately, the world has turned. People of my demographic who remember Lin Carter seem bizarrely happy to hurl money at his old books. I was fortunate that the local university had a copy in its library.

So, what’s in this book?

Good writing.

When he’s not writing fiction, Lin Carter turns out to be a supremely smooth and entertaining read. Better yet, he’s writing at a time before the classics of Fantasy had become sanctified. Robert E Howard is only a generation dead, Tolkien still lives.

Carter kicks off by claiming Fantasy as plausibly the oldest genre going back to the Epic of Gilgamesh (I disagree; a Neanderthal banging rocks together in 8:8 time isn’t the same thing as Rock and Roll.) However, he’s going to focus on the central tradition of Fantasy, this being — to paraphrase — “Adult stories set in new imaginary worlds where magic works.” T.H. White, Ariosto and Malory, for example, all belong on the periphery because they borrowed existing worlds. William “Really Messed Up Love Life” Morris, however, invented the tradition when, inspired by the German Sintram stories, he wrote the Wood Beyond the World. Burne-Jones, the great Pre-Raphaelite artist, did the illustrations — our genre is respectable!

Burne-Jones illustration from The Wood Beyond The World by William Morris.

Then follow six chapters of enthusiastic and gossipy literary history tracing influence and innovation through to Tolkien. He’s identifying a tradition, but also — I suspect — fixing it for all time. This book is probably the ultimate source of the imperative to explore the roots of the genre through reading Cabell, Dunsany and Edison. Carter is an honest Virgil, directing us to The Worm Orbourous, but rightly away from the lethargic Memison trilogy. He loves the Gormenghast books, but not the last. He enthuses us about the Islandia series, but admits modern readers may find them dull. We pass through the Pulp era — the names as familiar as those of the rock stars of a Woodstock line up — then learn about the British authors Hope Hodgson, TH White, and CS Lewis… all good stuff.

(But, is it good stuff? All this dusty old fiction evicted, often or not, from a dead man’s library to languish in the shoe boxes of used bookstores and the donated shelves of charity shops? That’s worth an article in its own right — but let me know what you think in the comments.)

Then we come to Tolkien.

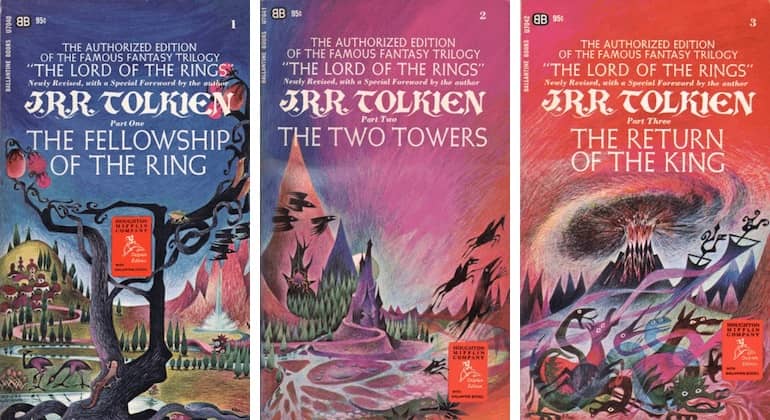

Covers by Barbara Remington

Lin Carter is not really a fan of Tolkien.

He’s read the The Lord of the Rings three times, and loves one or two passages, but isn’t in love with the whole.

It’s tempting to dismiss his criticisms the way you would those of a lead guitarist in a student pub Blues band laying into BB King, especially when he calls Tolkien’s prose pedestrian and his characters derivative. (Pot, Kettle…) However, if we grant him his editor hat, then he’s worth listening to, particularly when he’s agreeing with Fritz Leiber:

…The Lord of the Rings breaks down into certain favorite scenes and beloved characters, rather than lingering in the memory as a coherent whole.

Essentially, what my old English teacher used to say about Dickens: “Nice gargoyles, shame about the architecture.”

For Lin Carter, part of the trouble is the “essential shallowness”: for him, Tolkien’s villains are either local and petty — Leiber calls them “miserable sneaks, bullies and cowards”– or else godlike and cardboard, but still as undramatically knocked over. Overall, he sees no attempt to explore the nature of evil. (Me? I think it’s through the petty villains that Tolkien does explore evil; had Lin Carter been European and thus closer to the totalitarian regimes of the mid-20th century, he might have seen that.)

He praises Tolkien’s worldbuilding, to which we can attribute the impact and longevity of LOTR. However, he points out the elephant in the tower: What? No organized religion? No temples. No swearing by this or that god’s anatomy? How odd.

From there, via Erol Gardner’s Weirdstone of Brisingamen and Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain, we come up-to-date to the 70s and the LARPish Sword and Sorcerers Guild of America — SAGA — , dressing up and giving each other funny names. The real names are familiar enough to us: Le Sprague De Camp, Poul Anderson, Michael Moorcock… I’d love to have had a beer with them, perhaps they would have made me “the Marshal”?

It’s at this point that, from a writerly point of view, things get interesting, because now Carter turns to his thoughts about creating Fantasy, specifically on “world-making”, including advanced techniques, and on crafting fantasy names — I’ll talk about them next time.

M Harold Page is the sword-swinging author of Swords Versus Tanks. Go take a look at his latest novel, The Flying Tooth Garden Volume 1: The Jungle Tomb of the Ice Queen (A Reincarnation LitRPG)!

I read and reread this book back in the day, and still occasionally pull my paperback copy off the shelf. Like all very knowledgeable, highly opinionated people, Carter wasn’t always right – who is? – but his passion for fantasy lit a fire under me that has burned for almost fifty years and shows no signs of going out. When I think of all the wonderful books I would have never read but for him, I owe Lin Carter an immense debt, and I know that there are many more like me.

Great piece, Harold. My memories of the Ballantine series would mirror yours. They were a seminal influence. I think the first-rate critic and editor being a very second-rate writer of fiction is a pretty old syndrome, and Carter was a good example. His stuff was just so derivative – a sort of potpourri of Howard et al – without sufficient originality to transcend those influences.

I’m intrigued by this book, but I think you’re right: Carter was as much inventing a history of the fantasy genre as charting it. I’m surprised to learn he didn’t like Tolkien. Now, I much prefer ‘The Hobbit’ to LOTR. As I’ve said elsewhere, I like how the Low Fantasy preoccupations of the characters play against the High Fantasy setting (it’s basically a heist) and would regard the LOTR as a regression. And I can see where Carter is coming from. There was a discussion about orcs – again on tor.com – recently, and it made me think: some characters in LOTR are a very contemporary mixture of good and bad (e.g. Gollum is as pitiable as he is evil) while others are just plain wicked, the orcs being a case in point. How does that work? An entire race? So Carter is at least half right.

Are any of those old fantasy books any good? Any of them? I wonder. The fact that Lewis and Tolkien seem to be popular with more conservative-minded readers is a bit worrying. Even those authors who are correctly lauded as liberal in their outlook can be problematic. A recent analysis of Le Guin – again on tor.com – only made me more aware of her limitations. Sure she wrote her share of good books. She also wrote a lot of books that were dull and forgettable and maybe a bit too earnest for their own good. Plus I found Lieber’s stuff pretty indigestible second time round (likeable though he may have been) and so and so forth.

On the other hand, I re-read a couple of Clark Ashton Smith’s stories again a while ago (I’ve always been a big fan) and still reckon he’s one-off – he put a lot more effort into those stories than he really needed to. All the more impressive given that he didn’t even enjoy writing them!

I don’t think it’s fair to say that Carter didn’t like Tolkien. He was simply honest about JRRT’s faults, as a corrective to the uncritical adulation of LOTR that was more common at that time than it is now. He lavished high praise on Tolkien in his book on the trilogy.

As far as those “old fantasy books”, if I had to name the greatest fantasy novels I’ve ever read, The King of Elfland’s Daughter, The Worm Ouroboros, The Blue Star, Lud-in-the Mist, A Voyage to Arcturus, The Broken Sword, The Night Land, the Gormenghats trilogy, and The Well at the World’s End (Carter recommendations all) would be at the top of the list, and I think time has on the whole only verified Carter’s judgments rather than undermined them.

I’d certainly rather read these old musties instead of plunging into the latest multi-volume cookie cutter series. The older books, written before fantasy was even a distinct genre, give you a much stronger whiff of the strange than most things now. In my opinion, of course.

Egad it’s good to be back in such company.

Yes, Carter was an inspiration. There is also some value, in being a reliable comfort read, perhaps one reason why we return to his books.

I think in this book Carter pretty much damned Tolkien with faint praise. However, as TP says, he did go on to write about him more positively. So I should perhaps have used “doesn’t *love*” rather than *like* (though I was writing in present tense reporting the experience of reading the book…) This makes me want to read what he had to say about JRRT.

>Are any of those old fantasy books any good?

My personal take is yes and no. Novelty, style and relevance are context dependent. Time moves on and things become less novel – the John Carter movie suffered from this; all the tropes ERB spawned are now old hat – less well written, because the literary wheel has now been invented – and less relevant – we just, e.g., don’t care about family and honour the way we do.

So they were all good *once*, great even. Those that engaged with archetypes and owned them were less relevant at the time, but through a deeper relevance outlast their contemporaries. After that, it’s luck of the draw. Le Morte De Arthur is a good read because the simple 15th century style is closer to modern prose than a lot of the fiction in between, and because there is a novelty value in entering the world. King of Elfland’s daughter etc… personally I don’t find them that engaging; they are mostly no longer novel, and don’t offer the sense of a window into another time that Malory does.

> I’d certainly rather read these old musties instead of plunging into the latest multi-volume cookie cutter series. The older books, written before fantasy was even a distinct genre, give you a much stronger whiff of the strange than most things now.

I wrote a post about this! https://www.blackgate.com/why-i-read-old-science-fiction-stories-spoiler-for-entertainment/

The short of it is that modern books are too long.

Yeah, I don’t agree with everything in Imaginary Worlds (for one thing, sometimes he gets a bit too prescriptive about what constitutes “real” or “good” fantasy; a problem, ironically, that he shares with both Moorcock and Le Guin when they write about fantasy), but it’s an engaging, generally informative read that sits nicely on the shelf near de Camp’s Literary Swordsmen & Sorcerers.

And say what you will about Carter as an author (and his tendency to anthologize himself), but I owe him a debt I can never repay for his anthologies and for the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series as a whole.

Oops! Alan Garner’s Weirdstone of Brisingamen is the book we are looking for.

I admired Mr. Carter’s determined efforts to bring back the forgotten and original roots of genre fantasy, even if his better judgement prevented him from seeing what the fans wanted (i.e., more Tolkien derivatives – cf. The Sword of Shannara).

I think we may be doomed to disagree, but I head for the hills whenever that dreaded word “relevant” steps on the stage, mainly because I simply don’t know what it means in the context of imaginative literature, or if I do I don’t like it. For myself, I find The 125 year old Well at the World’s End just as “relevant” as the cutting edge Song of Ice and Fire books, and Morris’s language does something for me that Martin’s simply doesn’t. Enjoyable as the Ice and Fire books are (and I’ve read them all with real pleasure), in all of their many thousands of pages I have never encountered a single sentence which struck me as worth remembering or even momentarily savoring on its own merits because of its beauty or aptness. That matters to me, perhaps in fantasy even more than in most other kinds of writing.

Perhaps I should have used the term “resonant”? Books that hit contemporary themes perhaps make a big splash, but then fade as time moves on. That doesn’t make them bad, though. Books that hit archetypal themes resonate across time. And some books resonate for individuals. There are books I love that I would not casually recommend.

Funny, I was just thinking about Lin Carter this morning after reading his (utterly derivative) story in Bebergal’s “Appendix N” anthology. I, too, revered the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, and developed the opinion in my youth that Carter was a brilliant editor but his stories were, well, utterly derivative and unmemorable. I was wondering recently if it was time to rethink that opinion, but probably not. However, in the late Sixties and early Seventies, I thought Carter had the best job in the world, and eagerly bought every one of his anthologies. It wasn’t until I compiled an anthology myself that I fully realized how much work that was. We may have trash-talked his writing back in the day, but I’ll always be grateful to Carter for introducing me to Mervyn Peake.

I think he was a consistently good comfort read – which is not the easiest thing to achieve! I’ve enjoyed coming back to his stories because they are short and diverting. However, the Man Who Loved Mars was as good as Leigh Brackett, so he was able to write deeper and more emotionally involving, but perhaps chose not to.

I confess to reading a Carter novel now and then; once a year about does it. They’re short and what he lacks in originality (not what he was aiming for, anyway) he makes up in understanding and love of his chosen form. I understand that the last series that he started before his death, the “Terra Magica” books, are more serious and ambitious than his other work. I’ve never read them; maybe it’s time to give them a try.

Exactly!

I take exception to the idea that Eddison’s Zimiamvia books are any less powerful than The Worm Ouroboros. That sense of fantasy in reality, and the court politics that aren’t just backstabbing every other page, is something modern fantasy works could emulate more, I feel.

Yes. When I read them in my 20s, while studying Medieval History, I appreciated the way they captured that otherwhen vibe. I felt, however, that there was too much of them. Harold Lamb, a near contemporary, achieves similar effects more economically.

“The fact that Lewis and Tolkien seem to be popular with more conservative-minded readers is a bit worrying.” I’ll roll my eyes and move on…

Jim – I was only a child in the Sixties, but I can still remember how Lewis and Tolkien were icons of the counter-culture (if reluctant icons) and would reckon that generation latched onto what made the two such originals – their trippy world-building. Nobody paid much attention to the value-system underpinning each author’s work – and rightly so, imo – but that seems to be a big part of their appeal today. It’s not a good look.

I think setting isn’t manifesto. As I understand it, Tolkien was writing a sort of parallel mythology, so echoed those tropes. Kings and princes and warriors have epic-level agency, and are still archetypal on some weird deep level that’s nothing to do with politics and everything to do with destiny and duty. We can, for example, enjoy Beowulf and identify with the hero, without thinking warbands, raiding, and slavery are a good thing.

Great article! Thanks for the shout out. My 2013 article is at this link:

https://www.blackgate.com/imaginary-worlds/

I remember loving this book, though Lin Carter’s over-opinionated views could spoil it at times. I think of Carter as cut from the same cloth as DeCamp and Derleth. None of them, in my humble opinion, was a very good writer. Yet, each was a spirited fan whose joy of the genre was infectious when they wrote about it.

Regardless of Carter’s opinions, I think *Imaginary Worlds* can get the reader very excited about a bunch of different books and authors. I ended up buying a bunch of books because of Carter.

I certainly did likewise. I’m not sure how useful it was, but what we read builds who we are.

Aonghus, I would have called myself a “conservative” (hence my eye-rolling), but I don’t know what that word means to you; possibly an image that wouldn’t look much like myself. This site probably isn’t the place to pursue that topic much further. You are right that some people I would call conservatives do love their Lewis and Tolkien, and may have a very deep engagement with their writings. I suppose I owe about as much to Lewis as anyone can owe to another person simply on the basis of what that person has written. (For example, Lewis’s essay “On the Reading of Old Books” influenced me ever since I first read it 45 years ago, including the work I did as a college English teacher.) I’m glad that many people have read widely and deeply in the writings of Lewis and Tolkien, and some have read some study such as Dickerson and Evans’s Ents, Elves, and Eriador: The Environmental Vision of JJRT, etc. But if you’re a dedicated progressive, then, yeah, I imagine much in the thought of Lewis and Tolkien would not recommend itself to you. Even so — take a look at Dickerson and Evans & see what you think. (There’s a comparable book about Lewis by Dickerson and a collaborator with Arbol in the title, but I haven’t read it.)

And that’s your perogative, Jim. I’m not criticising you or conservative thinking per se (and am not sure I’m all that progressive tbh) – I was really thinking more in terms of demographics. I reckon Lewis and Tolkien had a broader appeal forty years ago than they do now. Maybe they’ve just found their natural niche? Either way, I’ll definitely check out Dickerson and Evans.

Demographics is an interesting point. A friend of mine is thinks that… call it… rural fantasy was popular because it harked back to landscapes that were still in living memory, e.g. my Great Grandmother ran a rural pub in Norfolk. The younger generations don’t have that connection.

Sounds good, Aonghus.

The book on Lewis is Narnia and the Fields of Arbol, by Dickerson and O’Hara. Like the book on Tolkien, it’s published by the University Press of Kentucky. It’s in their Culture of the Land series. When I read the Tolkien book, I was delighted to see the connection made between Tolkien and essayist, novelist,and poet P7WFWendell Berry (an admirer of Lewis’s That Hideous Strength).

Cheers!

Re Rural Fantasy. Although I think there are still plenty of people who enjoy hillwalking etc in the UK, it’s hard to imagine a rural poet like Houseman have the same visibility today. One thing that always strikes me about English writers of a certain vintage is how familiar they are with the names of flowers, trees etc. Lewis was a big walker. And what’s particularly striking about ‘The Hobbit’ (re-reading it a few years back) is the close attention Tolkien pays to landscape. He never describes a troll or a goblin in any detail, but we accept their reality because he’s gone to such pains to establish the country the characters are travelling through and by extension a context for such creatures.

Yes! And I think that though rural fantasy may fade somewhat, Tolkien won’t because there’s a slot for one or two authors who really capture that experience, and he owns it for all time.

‘I think setting isn’t manifesto.’

Sure. And most of us will accept that a medieval fantasy world is going to be less than progressive in its attitudes towards women, minorities etc. This need not reflect the author’s values (although I think sometimes it does) – but Tolkien is pretty unique in writing a children’s book without any female characters at all (‘The Hobbit’) and writing a sequel in which – while there were one or two important woman players – the vast majority were male. It’s a pretty odd world-view and was remarked on when the book first came out. I should hasten to add that don’t think Tolkien was a misogynist; just that the women seem to have been largely invisible to him (at least when it came to writing fiction).

I think that’s fair. He was also, I think, emulating Beowulf somewhat, which is also low on female characters. However…

Tolkien worked in the male-oriented environment of Oxford and his social circles tended to the male, as well. I feel the gender ratios of his book follow suit. On the other hands, the women who do appear in his works — Galadriel, Luthien, Arwen, Eowyn — tend to be brave, wise, powerful and often more level-headed than the men around them. Compared to the damsels in distress of some of the early copycat books that followed in his wake, it makes for an interesting contrast, I think.

…this seems like a good point. The women aren’t centred very much, but they leave a strong impression,

Aonghus, you are right about Lewis as a great walker — Tolkien was a walker too but Lewis found his friend’s pace a bit slow. Tolkien is on record that his favorite book when he was an adolescent was C. A. Johns’s Flowers of the Field, a guide to wildflowers. Through an intermediary, Dale Nelson got in touch with the late Christopher Tolkien, who reported the precise edition JRRT owned (since Johns’s book went through various editions). It is “Second Edition. Revised Throughout and Edited by Clarence Elliott. With 92 Coloured Illustrations by E. N, Gwatkin and 245 Cuts [i.e. black and white illustrations] in the Text. London: Routledge, 1908.” Nelson’s article about the book appeared in the May 2009 issue of the excellent monthly Tolkien newsletter Beyond Bree. There’s also his “Their Botanic Majesties’ Bequest: Tolkien, Morris, Potter, Haggard, Lewis.” Beyond Bree Aug. 2007: 1-5. These five famous fantasists were also noteworthy in various ways for nature conservancy, gardening, etc.

As for women in The Lord of the Rings, Stephen and Aonghus: it goes by a lot of people (it did me, for about my first ten readings), but a woman saved the world. Galadriel saves the world by what she does not do (take the Ring for herself) and what she does do (exercise prescience and give Frodo the Phial which enables him and Sam to survive Gollum’s treachery with Shelob). Moreover, the story is “presided over” by a “goddess,” Elbereth. A good book about Tolkien’s polytheistic monotheism has just been published, Sam McBryde’s Tolkien’s Cosmology from Kent State University Press.

Oh that sounds intriguing! Needs a review in Black Gate!

Yeah, that’s one of the things that really stood out to me on my last LotR reread — Tolkien conjures such an incredibly vivid sense of PLACE with the way that he describes the landscapes.

(Which, ironically, is also one of Lovecraft’s strengths, albeit used to different purpose — read the opening section of Dunwich Horror or Colour Out of Space when he’s luxuriating in hilly New England, or the way he talks about the cities he actually likes.)

Joe H., that’s a good point (importance of sense of place in Tolkien and Lovecraft). I’m afraid that many people remember scenes from the movies when they think of “Middle-earth”; but Tolkien lavished much attention to topographic detail in his great book. Try an experiment — just open the book more or less at random three times. I would guess odds are good that two of the three times, you will find that you are reading about people -walking-.

Any more, for me the descriptions of place in Lovecraft are perhaps the most important element in them. Take two of my favorites, “The Shadow Over Innsmouth” and “The Whisperer in Darkness.” I relish that bit early on in the one about catching the rattletrap bus and the ride to Innsmouth, and the material about the streams and dark woods earl in the other. There’s an expression that’s been associated with Bob Dylan and the music he & the Band were playing around the time of the Basement Tapes — “the old weird America.” Well, the bus ride in “Innsmouth” is a ride through the old weird America. I have probably read that material and not bothered with some of the other material in the story, like about the fishy-folk’s subaqueous realm etc.

One may have developed a sense of the enjoyment that writing about places can convey early on, when one read the Sherlock Holmes stories, notably The Hound of the Baskervilles.

Lovecraft is a sort of urban Tolkien, isn’t he? Rather than mountains and forest, he reads the cityscape, seeing the layers of history.

Your article took me right back to the early seventies, when I hoovered up as much of the Ballantine library as was available on this side of the pond. These days, I still like most of that old musty stuff Carter reprinted although I find the mock medievalism of William Morris very unpalatable. I read somewhere that Lin Carter had all the enthusiasm of the autodidact, along with the tendency for such a type to proclaim glaring errors as fact. His claim that Dunsany translated Horace from the original Greek, for example – Horace wrote in Latin. Yet, despite the glaring errors, his enthusiasm was infectious and, for me, came just at the right time so that a love of fantasy has stayed with me. I was surprised to see The Young Magicians anthology credited with a Fafhrd story. My copy does not have any story by Leiber. Neil

Egad you’re right! Where did I read that first story then? I swear it was in an anthology.

Hmmm … At a glance, I don’t see any Leiber in the BAF, although he does at least get name dropped/dedicated to once or twice.

Maybe it was in one of the earlier de Camp sword & sorcery anthologies? Or did they show up in one of Carter’s Flashing Swords volumes? Or his Kingdoms of Sorcery/Realms of Wizardry set?

Just checked the list of contents for ‘The Young Magicians’. Funny what you remember and what you don’t. I have vivid memories of ’Through the Dragon Glass’, ‘The Maze of Maal Dweb’, ‘Turjin of Mirr’ & ‘The Valley of the Worm.’ The Tolkien and Lewis poems didn’t really fit in with the overall vibe, being a tad too cosy for my tastes and‘The Way of Ecben’ was actively dreary. I remember enjoying ‘Ka the Apalling’ but nothing of the story itself.* The others I pretty much skim-read – if I read them at all.

* I must read it again.

[…] Another article about Imaginary Worlds: https://www.blackgate.com/2021/03/13/lin-carters-imaginary-worlds-1-history-of-fantasy/ […]