IMHO: Giving Voices to Your Characters

James Doohan (as Scotty): “I’m giving her all she’s got, Capt’n!”

I owe a great debt of gratitude to my two good friends, who were of immense help to me in the creation and shaping of my two (so far) volumes of Mad Shadows. Neither are strangers to Black Gate, for I interviewed both of them for this e-zine: Ted Rypel (author of the Saga of Gonji Sabatake: The Deathwind Trilogy, Fortress of Lost Worlds, A Hungering of Wolves, and Dark Ventures); and David C. Smith (author of the Oron series, The Fall of the First World Trilogy, the original Red Sonja novels (with Richard L. Tierney), Dark Muse, the recently-released Bright Star; Robert E. Howard: A Literary Biography, for which he won the 2018 Atlantean Award from the Robert E. Howard Foundation, and many other novels, including Waters of Darkness, on which we collaborated.) Both gentlemen write wonderful dialogue, and taught me how to make my characters “talk like real folks.”

Now, I don’t claim to be a great writer nor do I think I’m a “know-it-all” when it comes to plotting, creating characters, telling a story and writing crisp, entertaining and enlightening dialogue. I am far from being a literary genius. I’m not a college professor or a grammar Nazi. I’m not here to tell you what to do and how to do it. We each have our own styles and methods. I’m here to just pass on my own way of doing things, hoping what I have to say will help a writer or two. As far as creating compelling dialogue is concerned — and we’ve all heard this one — my personal rule is:

Give Each of Your Characters Their Own Unique Voice.

|

|

The Cecil B. DeMille Syndrome

One of the things that really bugs me, especially in the genre of Heroic Fantasy, is how so many writers have their characters “speak” in a very formal manner, like stilted dialogue from an old Cecil B. DeMille Biblical movie. Every line of dialogue is a declaration, a proclamation that sounds unnatural and unrealistic, at least to my ears. Or writers who try to outdo Shakespeare by using way too many words like “thee,” “thou,” “thy,” “thine,” “whence,” “whilst,” etc. Each character ends up sounding almost exactly like every other character: they don’t have their own distinctive “voices.” In “olden times,” uneducated peasants surely didn’t speak in the same manner as educated aristocrats. How many English-speaking people, for example, speak without using contractions? Not everyone says “cannot,” “it is,” “that is,” “will not,” and “shall not.” And slang isn’t an invention of the modern era; surely different classes of people in ancient Greece, Rome, Britain, and other countries had their own dialects, their own slang words and phrases. Just to give you an example . . . watch a lot of early films from the 1930s and 1940s. You’ll hear how people spoke, hear the slang and the phrases commonly used in those days.

When I first started writing, my dialogue was atrocious, to say the least. No contractions, too many “Biblical” words and phrases. I didn’t know what my characters’ voices sounded like. I didn’t know how they would talk to one another or what they would discuss. And they all spoke as if I was trying to channel the Bard. While I knew the “show, don’t tell” rule, so much of my narration, my exposition broke that rule, something I’m still guilty of to this day. Then I gradually learned how to turn a lot of my narrative into action, to “show it,” rather than tell it. Even more importantly, I learned how to turn narration into dialogue, to have my characters tell the reader what was going on in the story while they carried on conversations and discussions. Still, my dialogue rang false, and every character sounded alike. I had a “tin ear,” so to speak.

But I was learning.

The key is: mix it up. Create voices to match your characters’ personalities, level of education, and status in society. Have one character speak in a formal manner, have another use more slang and contractions, or another talk in broken English — as if English is not their first language. Be an eavesdropper. Listen in on conversations you hear in public. Pay attention to how people of different ethnic groups speak English, how they pause to collect their thoughts, and even the physical things they do when holding a conversation. (Of course, if you’re writing in another language—say French or German, the same applies.) Take notes on how people talk to each other. Listen to the inflections in their voice, the way they construct their sentences, the way they stutter or trip over their tongues. Pay attention to how they put emphasis on their words, and which words and phrases they use over and over again, such as “like,” “you know,” “you think?” and “see what I’m saying?” These are their “tag-lines,” their trademarks. One of the things I love about living in Chicago is the diversity of cultures, the many languages and accents I’ll hear just sitting in a restaurant for a few hours. I try my best to capture some of the voices I hear.

Dialogue Is Action

Over the years I’ve encountered many readers who dislike dialogue, stating that too much of it slows the pace of a story. They find it needless. They want fast-paced narrative, with plenty of action. They aren’t interested in the characters so much as they’re interested in the plot, the battles, the monsters, and the sex scenes. But I disagree. Dialogue is verbal action: it can and should be used to advance the plot. Character interaction is, in my mind, essential to almost every story. Human drama is a key factor in engaging your readers, making them live the story through the words and thoughts, hearts, eyes and emotions of your characters. Dialogue enhances characters; it lends them a depth and realism that will make them leap off the page. What grabs me, what sucks me into a story is how the characters interact and relate to one another. Without dialogue, what would Shakespeare have done? Without dialogue we’d have no live theater, without dialogue, we’d have no need for talking pictures; we’d still be watching silent “picture plays.”

Don’t lecture: Discuss. Debate.

If you have a very long passage where one character is addressing a group of people — I call it “Giving the Speech” — and it goes on for a page or more, break up the dialogue with a little bit of “stage business.” Have the character pause to drink some water, light a cigarette, blow his nose, or have the speaker be interrupted by other characters . . . anything to make it more exciting. While dialog can drive the plot forward, long passages of it can slam on the breaks as surely as endless descriptions of what people are wearing or what a room looks like. The trick is: never preach, never lecture for pages on end; then it becomes a monologue, a soliloquy if the scene. If you have something of import to say, keep this in mind: yours isn’t the only opinion. The late broadcast journalist, Jim Lehrer, had a set of rules for journalists. Number three holds true for writers of fiction, too: Assume there is at least one other side or version to every story. So, if your character is giving The Lecture or The Speech, add some fire to it by having another character voice his or her own opinion. Create some tension. Posit some differing views. If it’s a political, philosophical or religious belief or idea you want to get across, add some confrontation and argument; let the characters discuss and debate: don’t have one character monopolize the entire scene. (We are not Congressmen, after all.) If it involves a sermon or a professor giving a lecture, keep it as short as you can, using only the necessary and important talking points. Above all, make your dialogue fun and interesting to read, make it sound natural; have characters disagree and argue a point. And remember, unlike Lehrer’s Third Rule, where he states “I am not in the entertainment business” — writers, however, are entertainers.

|

|

|

|

A Few Tips and Tricks

If I can’t find my character’s voice, I look to old movies for inspiration, to actors and actresses whose voices and patterns of speech I think will be suitable, and I try to emulate those voices. Old movies are great for this because there was a vast array of character actors who were great at ethnic accents, plus so many actors from other countries who had thick accents and a unique way of talking. In the stories I write for Janet Morris’ Heroes in Hell™ series, two of my recurring characters in the series are Doctor Victor Frankenstein and his lab assistant, Quasimodo, the Hunchback of Notre-Dame. For Victor, I looked to the voice of Colin Clive, the actor who played the infamous physician in the 1931 Frankenstein starring Boris Karloff. For Quasimodo, I gave him a bit of actor Charles Laughton’s voice, from the 1939 version of The Hunchback of Notre-Dame, although I try to add a bit more eloquence, and sprinkle his dialogue with some French words and phrases, and endeavor to have him speak like a Frenchman for whom English is a second language. And that’s something else I’d like to pass on to you.

During a screenwriting class, the instructor gave me a suggestion for one of my screenplays, in which I have an American woman, an Irishman, a Spaniard, and a proto-feline, alien medic. I had the woman speak like a hip, modern-day woman. For the Irishman I chose actor Victor McLaglen’s voice, using words and even some old phrases my Mom and a few Irish family members used. For the alien, I chose some odd phrasing for him, but what he never does is use the words “I,” “me,” “my,” or “mine.” He always refers to himself as “this one” or “this mewling.” Example: “This one would like very much to try this beverage.” Or “This mewling is so very much unhappy.” But for the Spaniard, I had some trouble. The instructor suggested I have him speak English as if he was speaking Spanish. Hombre gordo in Spanish is “fat man,” with the adjective following the noun; he would say, “O’Hara, you are a man who is very fat.” The Spaniard, as it turned out, was the most eloquent of the three characters, and I finally found his voice in actor Pedro Armendariz. That screenplay, by the way, became the basis for my space opera, Three Against The Stars. For my German, Dutch, Italian, and other ethnic characters, I’ve done the same as I did with my Spaniard, often relying on the voices of various actors to help me nail it all down. In Dave Smith’s and my Waters of Darkness, the main character, the pirate Captain Angus “Bloody Red” Buchanan is Scottish. Now, how to capture his voice? I didn’t want to go the route of H.P. Lovecraft and misspell words to sound the way a character speaks, although I did substitute “dunno” for “don’t know.” What I did was watch a few movies to help develop my ear, but my main inspiration was actor James Doohan — Scotty, from the original Star Trek television series. I used words in different patterns for Bloody Red, just to give it a Scottish flavor without going overboard: less is more. He never says “I will not do that” or “I won’t do that.” He says, “I’ll no’ be doing that.” In place of “my lad” or “my bonny lass,” he says “m’lad” and “m’bonny lass.” Instead of saying “The man who buried that treasure,” he’ll say “The man what buried that treasure.” Just little things like that. I didn’t want to overload his dialogue with too much of a Scottish accent that I felt would only be distracting for the reader.

Create some signature line or phrase for your characters. Think of Gollum’s “My precious;” John Wayne’s “That’ll be the day!” from The Searchers; think of Sam Gamgee’s quaint way of speaking, always calling Frodo “Mister Frodo,” and always talking about food; or the oft-quoted, “I’ll make ’em offer they can’t refuse.” It’s the little things that often carry the greatest effect you can create for your characters. And don’t forget: not everyone is grim and dour; put some humor into your dialogue. Cops, soldiers, mobsters . . . they all joke among themselves; they all tease and bust each other’s balls. Drama is more effective with humor, and comedy has a sharper bite if there’s some drama behind it, some element of danger. If you can’t come up with a signature phrase, use the way a character speaks, his tone of voice, his attitude. Is he arrogant and sarcastic? Vulgar and mean? Respectful and proper? Sardonic and overly dramatic? A little of this can go a long way in helping to shape your characters, define who and what they are. And don’t forget the posturing. A character’s body language also adds to your story.

|

|

Films As A Source Of Inspiration

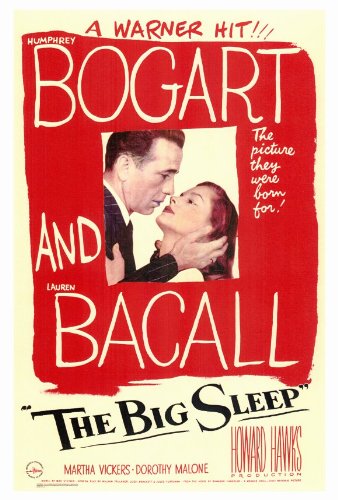

If you’re having trouble finding a voice for one of your characters, turn to films for inspiration. In Sunset Boulevard (screenplay by Billy Wilder and Charles Brackett), washed-up silent film actress Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson), when talking about the silent film era, tells Joe Gillis (William Holden) “We had faces then.” Well, I look to old movies of the 1930s thru 1950s for my “voices” because “They had voices then!” This is just personal preference, and not everyone enjoys those old films. But I learned a lot about writing dialogue from many films of that era, such as Casablanca (screenplay by Julius J. Epstein, Philip G. Epstein, and Howard Koch; based on the play, Everybody Comes to Rick’s, by Murray Burnett and Joan Alison); and The Front Page (based on the play by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, who was the father of Hawaii 5-0’s James MacArthur; the film was later remade as His Girl Friday, by director Howard Hawks, with a screenplay by Charles Lederer.)

In the film industry there’s a phrase pertaining to dialogue that is obvious, straight to the point, with no dissembling and no attempt to hide a character’s motives or true self. This type of dialogue is called “on the nose.” Characters don’t always say what they mean, or mean what they say. Subtext goes a long way, and it can be fun, too. While being “on the nose” in a novel or story is more common, using subtext can enhance a scene, make it more interesting. In the glory days of Hollywood, before the sexual and verbal revolution, screenwriters had to walk a high-wire act. Subtext was king. For instance: in the first screen version of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep, (screenplay by William Falkner, Jules Furthman, and legendary fantasy and sci-fi author Leigh Brackett,) there’s a scene where Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall are flirting and sizing each other up, sexually. What they’re doing is obvious. But their dialogue isn’t. They’re discussing horse racing, but the subtext of the scene is not about horse racing, it’s about sex. Likewise, in the film version of James M. Cain’s Double Indemnity, (screenplay by Raymond Chandler and director Billy Wilder), there’s a hot scene where Fred MacMurray and Barbara Stanwyck are also sizing each other up, but they’re discussing being pulled over for speeding by a traffic cop. The dialogue doesn’t match the looks the actors are exchanging, or MacMurray’s fixation on Stanwyck’s ankle bracelet, but the subtext is there, boys and girls. They’re talking about S-E-X. If you get it right, subtext can be fun to read, and fun for the writer, too.

On Telling the Reader Who’s Doing the Talking

As I stated earlier, dialogue is action, and no one can talk me out of that belief. Dialogue can be a lot of fun to write, especially when you have the “voices” of your characters nailed down. You can just let them interact, verbally letting us into their worlds, their characters, and also helping to push the story forward. But don’t let it get too boring, and I’ll give you a few tips on avoiding that pitfall. First, there is nothing more annoying to me than continuous lines of dialogue that end with “he said,” “she asked,” “he told her,” “she said to him,” and variations thereof — especially when there are only two people in scene holding a conversation. You can skip a lot of that, as well as reveal insight into a character, keep the story moving, and pass on valuable information. For example, you can try doing this:

Unless absolutely necessary that you begin a scene “at the beginning,” utilize what many screenwriters do: come into the middle of a scene. Of course, you can begin with a few sentences to set the scene, but you don’t need to spend a page or more doing it. No need to go into intricate detail: less is more. Let the readers’ imagination fill in the blanks and create the setting in their own minds. Describe only what is necessary to understanding the characters, and what is essential to plot and story. Remember what Anton Chekhov (1860-1904) once said (and here I paraphrase): If there’s a gun on the mantle in act one, make sure that gun is used by act three, otherwise, why put it on the mantle in the first place? Screenwriters call it a “plant” and “foreshadowing events to come.” Clues to past or future events, basically.

Jane and Joe Demonstrate Dialogue:

Jane sat at the kitchen table across from Joe, watching him fumble with a pack of cigarettes. She noticed how the sunlight gleaming through the open window made the dull, orange paint on the walls look brighter than they were. A soft breeze blew in through the open window, ruffling the faded purple curtains.

Joe’s hands shook as he lit a cigarette. “Do you think he’s behind it all?”

(Here we’ve learned that Joe smokes, and he’s nervous. You don’t have to type “he asked” because we’ve already “tagged” Joe, and the question mark is there to tell us that he’s asking a question.)

“No, I don’t. Not at all.” Jane reached into her coat pocket, pulled out an envelope and slid it across the table towards Joe. “I swiped that from his wallet while he was sleeping.”

(You don’t have to say “Jane said” or “Jane replied,” [or even “he said,” “she asked,” and “Jane told him] because first, they’re the only two people in the kitchen. Second, the narration after Jane’s reply shows that she’s the one doing the talking here. We’ve revealed that Jane is a thief. Also, we’ve just created a little mystery here: who is Joe talking about? What’s in the envelope? What’s going on between these two and why did Jane steal the envelope? These are questions that can be addressed through dialogue as the scene progresses, or can be answered later in the story through dialogue or narrative.)

“You’re a wicked woman, Jane.”

(No need to type, “Joe said,” we know he said it because he addressed her by name.)

Jane held out her hand. “Flattery may have gotten you to first base, but only money will get you to home plate.”

(No need to type “Jane said,” because we tagged her before she spoke.)

You can go back and forth like this, either having the characters doing things while they talk, or you can just type out the dialogue without any action, and maybe every sixth or seventh line of dialogue you can throw in a “he said” or “she asked,” just to keep the reader on track. Of course, when you have more than two people conversing in a scene you’ll need to establish who’s doing the talking at any given moment either by adding some bit of “stage business” for them to do or by using a “he said” or “she asked” or “he replied” now and then. Just don’t overdo it.

Writers like Paul Cain and Elmore Leonard would write pages of dialogue without using any exposition and character business, without telling us who’s talking. You just have to keep up with them and their characters.

You can also reveal a character’s emotions and even their thought process using a bit of stage business to coincide with their dialogue. You don’t have to use “The Wrylies,” which is a screenwriting term often used when describing how an actor should deliver a line, using such words as wryly, angrily, heatedly, and so forth.

Joe threw the empty bottle of beer against the wall, where it shattered into tiny pieces. “I don’t care what he says, I don’t believe him.”

(We’ve just shown Joe’s anger through action, without telling the reader “he said angrily,” and without even using an exclamation point — which many writers — including yours truly — are guilty of overusing.)

“But I do, Joe.” Jane wiped a tear from her eye. “I really do.”

(Here we’ve established Jane’s emotional state by showing, and not telling.)

Taking a long drag from his cigarette, Joe exhaled a smoky sigh. He was about to take a second lungful of smoke but then quickly stubbed the cigarette out in the ashtray. “I know you do. I just wish there was something we could do.”

(Here we show Joe’s frustration through his words and action.)

Jane pointed a finger at Joe. “You never listen to me!”

(Here we’ve let the reader know, by Jane’s action, that she’s talking directly to him. It helps when there are one or more other characters in the scene.)

Anyway, you get the picture. Good or bad, these are just examples of what you can do. You don’t need to, and shouldn’t, show action with every line of dialogue. Break it up with just dialogue for a few lines, then some action, and the occasional “he said” or “she asked.” You can also do this when you have more than two people conversing in a scene. Main thing is, use your imagination: thinking up what characters might be doing during a conversation can be a lot of fun and hold the reader’s interest. Observe what people do, how they look and react when they’re involved in a conversation. No one sits perfectly still during a conversation.

In Closing

My advice to young writers is always first and foremost: know the genre you wish to work in. Don’t just write with an eye towards trends and fads; look for ways to twist things around and make them your own by branding your tales with something different, something unique. And you can find ways to do all that by reading outside your genre. For over 20 years, starting in the early 1960s, I read nothing but heroic fantasy, sword & sorcery, horror, and science fiction. I’ve read enough to know the genre, I think, and I’ve surely been influenced and inspired by all that I’ve read. But I broke away to read other genres — although I still dip an occasional toe in the water of the genres in which I write in. There’s so much else out there, though: histories, mystery, crime, WWII thrillers, westerns, romance novels, biographies, and so on. I’m sure everyone has their favorite authors, authors who influenced and inspired them. Study their dialogue, how they write it, how they present it, what they have their characters doing — from twiddling their thumbs to toying with a knife, from tapping a tabletop to dicing a chicken breast with all the precision of a skilled surgeon.

As the title of this article infers, this is just my humble opinion. I’m just here to share what I know, what I do, what I like, and what works for me. I hope all this has been of even a small source of inspiration to some authors who are just beginning their journey.

Thank you!

Joe Bonadonna is the author of the heroic fantasies Mad Shadows: The Weird Tales of Dorgo the Dowser (winner of the 2017 Golden Book Readers’ Choice Award for Fantasy); Mad Shadows II: Dorgo the Dowser and the Order of the Serpent; the space opera Three Against The Stars; the Sword-and-Planet space adventure, The MechMen of Canis-9; and the Sword & Sorcery adventure, Waters of Darkness, in collaboration with David C. Smith. With co-writer Erika M Szabo, he wrote Three Ghosts in a Black Pumpkin (winner of the 2017 Golden Books Judge’s Choice Award for Children’s Fantasy), and The Power of the Sapphire Wand. He also has stories appearing in: Azieran—Artifacts and Relics, GRIOTS 2: Sisters of the Spear, Heroika: Dragon Eaters, Poets in Hell, Doctors in Hell, Pirates in Hell, Lovers in Hell, and the upcoming Mystics in Hell; Sinbad: The New Voyages, Volume 4; and most recently, in collaboration with author Shebat Legion, he wrote Samuel Meant Well and the Little Black Cloud of the Apocalypse. In addition to his fiction, he has written a number of articles and book reviews for Black Gate online magazine.

Visit his Amazon Author or his Facebook Author’s page: Bonadonna’s Bookshelf

Joe Bonadonna has been a contributor to Black Gate since 2011, most recently interviewing David C. Smith (October 2019).

|

|

Great advice Joe. I’ve adored the Dorgo novels, partly because “his” voice is so natural. He obviously reflects the Grim Noir in you.

Seth Lindberg and John O’Neill – once again, thank you for such a splendid presentation and layout of my article. Always a great pleasure doing business with you guys, and Black Gate.

Seth Lindberg – thank you again for your praise and kind support. You rock!

Great tips, Joe! I took 3 creative writing classes at 2 different colleges on my way to a BS and an MS in English, and all 3 instructors had much to say on dialogue. One tip all 3 agreed on was that “said” was often adequate enough, that overly descriptive adverbs got in the way, telling rather than showing; your bit about interspersing action with dialogue is a prime example of how well that works. My uncle called that excessive adverbial modifier usage “Tom Swiftisms”: “‘This room is like a refrigerator,’ Tom said coldly” is an example. His all-time favorite was “‘Take the prisoner downstairs,’ Tom said condescendingly.”

One of my instructors invited a published writer to our last week of classes. Robert Flanagan had written a book, “Maggot,” about his experiences in the Marine Corps. He told us about his difficulties learning to write halfway decent prose, since he tended to get too detailed on occasion. In one story, he had a man sitting on a chair in a room and had to get him out of that room. He wrote something like this: “He stood up, walked across the room to the door, grabbed the door knob, twisted it, opened the door, and walked across the threshold.” He agonized over this until he suddenly realized how long it took the character to accomplish a simple move, when all he really had to say was, “He got up and walked out of the room.”

smitty59 – thank you! I learned a lot from writing classes, reading books by long-accomplished writers, and from magazines like The Writer and Writer’s Digest, and even Script (or was it Screenplay?) magazine. I more often than not use just said, replied, told me (or him/her), explained, and answered, just to break things up. Lately I’ve been deleting “asked,” because the question mark says is all. Often, instead of the adverb, when I need to let the reader know the tone of someone’s voice or the manner in which they said something, I either preface the dialogue with a brief description, or follow up with something like: Her voice was cold and far from friendly; especially in a first-person narrative. I tried to read a novel that was “allegedly” (I never looked into it) a contender for the Pulitzer Prize. But I gave up on it because EVERY line of dialogue, even in a 2-person scene, ended with either “he said” or “she said.” It annoyed the heck out of me!