Godzilla Minus One Is One of the Crowning Achievements of the Series

The Godzilla franchise turns seventy next year, and 2023 has been chock-full of new G-media to get everyone amped. Godzilla: Tokyo S.O.S. and Godzilla 2000: Millennium got special theatrical re-releases. Shigeru Kayama’s original novelizations of Godzilla and Godzilla Raids Again were finally published in English translations. AppleTV produced Monarch: Legacy of Monsters, a new episodic series based on Legendary’s Monsterverse. Toho released new short Godzilla films with the famous monster smacking around Gigan and Megalon in old-school grudge matches.

The biggest gift arrives this weekend: Godzilla Minus One, Toho’s first live-action film since 2016’s Shin Godzilla. And what a gorgeous, furious, thrilling, tear-stained gift it is. It’s a fitting anniversary homage to the creators of the 1954 classic, especially original director Ishiro Honda, and easily one of the best Godzilla films—and best giant monster films—ever made. It places Godzilla into a period setting for the first time and fills the screen with exciting kaiju terror and an engrossing human story that doesn’t exist just to string along the spectacle. This is the Godzilla film that conventional wisdom says couldn’t be made. Yet here it is … because conventional wisdom is rarely genuine wisdom.

Since this December doesn’t have an epic franchise installment people actually want to watch (nobody cares about another Aquaman flick or a vomited-up Willy Wonka prequel), this is the blockbuster of the season to see in theaters. And I can recommend Godzilla Minus One to everybody, not only fans of kaiju flicks and SF mayhem. A Godzilla film only Japan could have made, but unlike the localized-to-obscurity Shin Godzilla, a Godzilla film all the world can appreciate. What an achievement.

Written, directed, and with visual effects by Takashi Yamazaki, Godzilla Minus One breaks away from several G-series staples while embracing others not seen in decades. The story structure has a solid foundation familiar to anyone who’s seen a giant monster film: a monster emerges, causes massive urban destruction and smashes apart the military’s attempts to stop it, and then a group of scientists and other ingenious folk craft a scheme or weapon that might be able to destroy or drive back the beast. This is the structure of the original Godzilla as well as the far weaker The Return of Godzilla (1984) and Shin Godzilla. What Yamazaki removes from the formula are the more science-fiction elements like enemy monsters, aliens, future-tech, and special kaiju-battling government agencies. The unique setting of Japan in the immediate postwar years dictates a realistic style, pace, and grubby aesthetic. This is a dirt-and-shanty Godzilla film, as if lifted from Akira Kurosawa’s docudrama Stray Dog (1949); a world where the rampage of a giant radioactive reptile is only a few summers removed from the nation’s greatest tragedy and shame.

Godzilla movies by their nature are tricky to craft as character-driven pieces. This isn’t always a negative. Some of the best G-films use humans as inessentials shoved into the shadows by Nature the Uncaring God. The more the monsters dominate, the less the humans have meaning. The 2014 US Godzilla is a great example of this style. Other Godzilla films use humanity as a collective protagonist rather than individual characters. Ishiro Honda often favored this broad humanist approach in the movies he made in the 1960s; Shin Godzilla also took this tact.

But it’s wrong to claim that Godzilla movies always lack substantial characters, an assumption I’ve noticed many mainstream reviewers asserting as they praise Godzilla Minus One. Honda’s Godzilla has excellent characterizations and quiet moments similar to the contemporary films of Yasujiro Ozu and Mikio Naruse. Even Honda’s kiddie-targeted All Monsters Attack (1969) depends on fully developed characters and everyday life for most of its story. (Yes, I just favorably compared All Monsters Attack to Godzilla Minus One. This is a big tent franchise, one reason I love it so much.)

It’s this personal side of Ishiro Honda’s filmmaking that Yamazaki emulates for Godzilla Minus One and why it resonates as an anniversary work. Honda was a veteran of World War II and his memories of its death toll and waste often haunted him. Yamazaki pulls from Honda’s postwar life and makes it the engine of his film: intimate drama interspersed with an epic where people must unify beyond the normal structures of the world such as governments and outdated codes of honor. Even in a country ruined by war and struggling to find a future, the story finds hope and looks ahead to a new national character.

Yamakazi’s screenplay centers on a family that develops out of the wreckage of the war and other shattered families. Koichi (Ryunosuke Kamiki), a former war pilot racked by survivor’s guilt, becomes the protector of an orphaned young woman, Norito (Minami Hamabe), and Akiko, an abandoned infant Norito rescued from the streets of Tokyo and has taken to raising as her own. This ad hoc family enlarges to include Koichi’s colorful pack of co-workers in his new job on a small minesweeper doing clean-up duty in the ocean. Although Koichi’s homelife starts to resemble a husband-wife-child trio, his self-hatred makes him refuse to accept this. To him, this “family” is only victims of circumstance accidentally tossed together.

Then Godzilla rises from the ocean depths with its crushing feet, hydrogen-bomb fueled mutations that can snuff out tens of thousands of lives at once, and utter disregard for life—a disregard that only warfare can exceed.

This is where Godzilla Minus One reveals its ingenious theme that makes it succeed as both monster spectacle and human drama. Godzilla is a metaphor for war in general rather than only atomic power (although the atomic metaphor is still present, mostly done through visuals). Godzilla becomes the extended reach of World War II, inescapable even for those who survived it.

This extension of the war forces the characters, both as individuals and as a collective, to confront part of the Japanese warrior honor code that frames surviving as failure. This interrogation of the kamikaze code becomes the spine of the film when the civilians of Japan are left on their own to defeat Godzilla. The occupational Japanese government is useless and US forces refuse to become involved out of fear of igniting tensions with the Soviet Union, so it’s up to a coalition of civilians and former soldiers, naval officers, and engineers to confront and defeat the seemingly undefeatable.

The bridge between monster-scale action and human-scale drama is Koichi. A kamikaze pilot who failed at the suicide part of his job definition, Koichi carries the weight of a failure of honor on his shoulders. His survivor’s guilt is made worse because the same day he chose to land his plane at a military depot on a small island rather than carry out his bombing run, he also couldn’t do enough to save the garrison of technicians on the island from being slaughtered by a thirty-foot-tall dinosaur-like creature. He comes home from war a pariah, and even as he builds a family with Norito and Akiko, he refuses to let himself truly live. He won’t even acknowledge his family as a family, telling little Akiko to stop calling him “father.”

Koichi never expected the shadows of his war failures to come back in such a devastating way: the monster from Odo Island, now irradiated from the American Bikini Atoll test into a 180-foot-tall unstoppable moving disaster area. Koichi’s family life again changes to tragedy, and he volunteers for the civilian anti-G plan with hopes he can correct his “error” of surviving. The finale captures a similar emotional power to the ending of original Godzilla, but with a unique change. It’s the climax the film has earned, and it’s as satisfying a close to any giant monster film I can imagine. I think Ishiro Honda would have loved it, and even non-fans may have to wipe away tears before the credits roll.

It’s wonderful to have excellent human drama and serious themes about war and the reevaluation of an ancient sense of what honor means. But this is still a Godzilla film, and in a Godzilla film the monster’s part must work or nothing will. And hell yes does Godzilla and the spectacle of its destruction work. Japan’s film industry has now proved they can pull off a Godzilla film with a CGI version of the monster, something I worried might be impossible. I’ll always love “suitmation” as a beautiful visual effects style, but the CGI monster effects in Godzilla Minus One left me stunned. After a year of numbness from empty VFX action in failed blockbusters, it was such a relief to again feel amazed and moved by special effects mayhem. Especially in a movie theater, because the cinema screen is the best habitat for giant monsters.

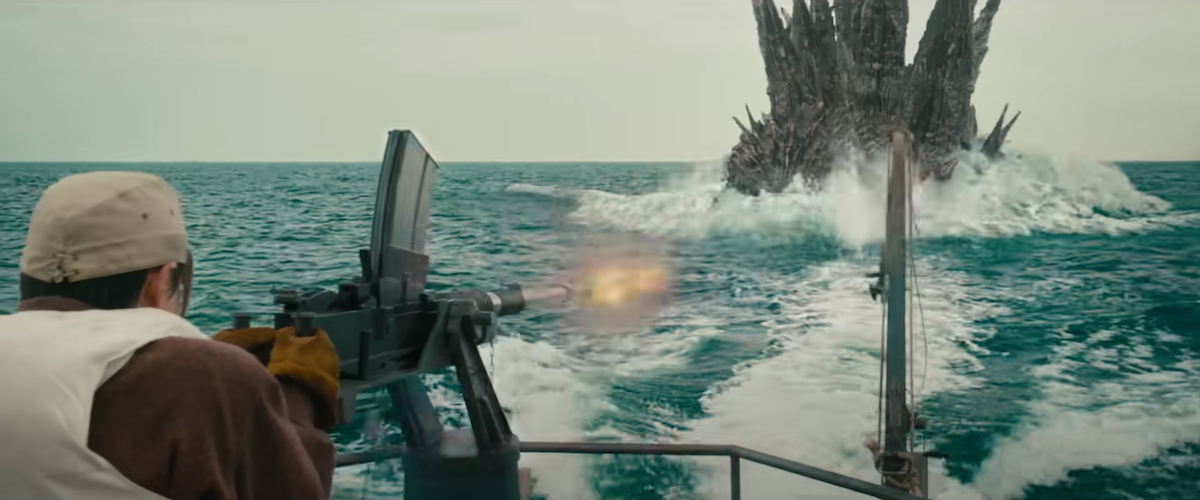

The four major Godzilla VFX set-pieces are unique in staging, which includes not only a whopping centerpiece of city demolition, but also a tense homage to Jaws unlike anything seen in the series before. The execution of this boat chase makes Godzilla into a suspenseful terror to a small group of people without diminishing the monster as a force of nature that’s above caring about humans.

Although there are a few special effects deficiencies, they hardly matter. Most of the effects are stunning and have an impact many modern blockbusters lack. It’s a visceral thrill to feel the crash of enormous feet flattening crowds, to sense a vertiginous tilt as a collapsing building tumbles into the street. Few G-films have shown what an astonishing toll in lives and property the monster can inflict. It’s tactile, energizing, and horrifying.

Godzilla’s atomic ray is the most spectacular and viscerally effective version of the monster’s signature weapon. Some of the tensest moments hinge on watching that harsh blue glow crawl up Godzilla’s spikes, each one snapping into place like relays clicking shut to ignite a bomb. The ray appears only a few times, but like everything else in the VFX sequences, it has greater impact than mere CGI sparkle. What Godzilla does matters, both to the people on the screen and the viewers experiencing it.

To push the monster scenes over the edge, the soundtrack turns at the right time from Naoki Sato’s solemn, almost medieval original score into Akira Ifukube’s famous themes. Ifukube’s music is the signature sound of the series, as essential to Godzilla as John Barry’s music is to James Bond; but other Godzilla films often shoehorn it in without much thought. (Shin Godzilla is extremely guilty of this.) Godzilla Minus One is the best deployment of Ifukube’s music within another composer’s score I’ve heard yet. Even people who don’t know a single note of these themes will feel a jolt when they pound into the soundscape.

Godzilla Minus One is already a hit in Japan, so what comes next for Toho’s Big Bad? Since I appreciate the tonal variety of this series, I want the next movie to be absolutely ridiculous. Alien invasions! Atlanteans! Have Megalon show up! Maybe even Varan—wouldn’t that be so random? I want Godzilla to do flying kung-fu kicks and punch perfectly round holes through its adversaries. Maybe Godzilla x Kong: The New Empire next year will scratch that itch. Just pump all those radioactive flavors of Godzilla into my veins because I’m so happy right now.

Ryan Harvey is the author of the novel Turn Over the Moon. He lives in Southern California where he studies Godzilla, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and for some unfathomable reason also performs improv comedy.

I totally agree with you, Ryan. This movie is fantastic and as good as the original, and in my opinion, better than the original because I enjoyed the humans’ story much more. Go see this movie if you have any interest in seeing an emotionally rich giant monster movie, as bizarre as that may seem.

I haven’t seen it yet, but all this enthusiasm from true believers is definitely sharpening my interest.

I don’t think it did that well on opening weekend. I hope it has legs in theaters.

It made $11 million in US theaters this weekend, which is above expectations, landing it in third place and beating new release “Silent Night” and also beating the second week for “Napoleon” and “Wish.” That’s EXTREMELY good for a foreign language film. And it’s already been a massive hit in Japan. I do expect it to continue to play well through the season.

[…] (Black Gate): The biggest gift arrives this weekend: Godzilla Minus One, Toho’s first live-action film since […]