Fiction Excerpt: “The Wily Thing”

By Constance Cooper

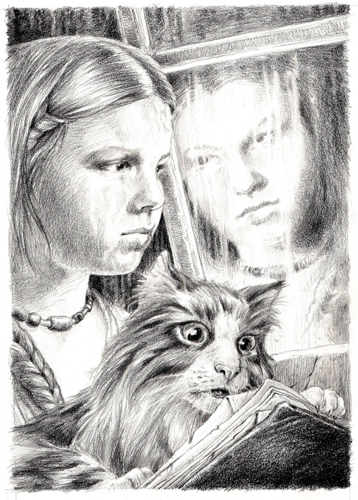

Illustrated by Michael Vilardi

from Black Gate 12, copyright © 2008 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

Yonetta DuRoy, or Yonie Watereye as she now styled herself, lived under false pretenses in a stuffy garret overhanging the Petty Canal in one of the cheaper districts of Wicked Ford.

Yonetta DuRoy, or Yonie Watereye as she now styled herself, lived under false pretenses in a stuffy garret overhanging the Petty Canal in one of the cheaper districts of Wicked Ford.

Now the Petty could be scenic, up in the high side of town where it slid between steep flowered banks, and the ladies clustered like petals around dainty cafe tables. The Petty could bustle, down near the High Road by the inns and the water market. But where Yonie lived it was not lovely or lively. Dry land never showed even in the midst of summer, and the rickety buildings roosted up on wooden pilings that would have rotted long since but for the water’s high concentration of guile.

Yonie’s garret was a narrow, slope-shouldered room in which anyone of adult height could stand only immediately below the spine of the roof. (As of late, that had included Yonie, but she made do because the rent was cheap and the landlady asked no questions.) In one of its two vertical walls, the garret had a stingy window that might once have been a vent. It provided a view of the canal through gum tree leaves, and on hot days, a swampy canal-odor like an army’s dirty laundry. The opposite wall held another window-vent and a door that opened to a tacked-on balcony barely strong enough to hold the weight of the rain-barrel at one end. Shaky steps led down through several switchbacks to the boat-slips and floating trash behind the building.

Unlike most garrets in that neighborhood, which was neither famous nor infamous enough to have a name of its own, Yonie’s had a collection of books. She stood them in the otherwise useless space where the roof angled into the floor, and had so far in two years there filled almost one long side of the room. They ranged from treatises about ancient history (mainly dull with a few useful nuggets) from the cut-price boxes at the water market, to collections of travelers’ tales (mostly lurid) splurged on when business was good, to The Unlucky Prince (the only one of her childhood favorites to survive, since she had had it with her in the canoe that night.) Other than that Yonie’s furnishings were quite ordinary — a small table, two mismatched chairs, a meager stove, a bed of reed matting behind a curtain. Assorted cheap pans and crockery stood at attention on homemade shelves, and a chamberpot crouched discreetly out of sight. The only thing a visitor might remark upon would be the profusion of pillows, and perhaps the way a shingle had been loosened and propped open, like a miniature trapdoor, in the roof above.

On that particular late summer afternoon the air in Yonie’s garret was humid and still, caged in by the closed door and shuttered windows. Yonie’s hair was crawling with sweat underneath her head-kerchief. She imagined it soaking all the way down her long brown braid, past the blue wooden beads tied at the end, and dripping off the point like a wet paintbrush. She longed to strip off the kerchief and throw open the windows and the door to catch what breeze there was.

But instead she sat sedately in her chair, sweltering, because she had a customer. The kerchief made her look older, according to LaRue, and she needed every bit of age she could claim. Although she’d already sprouted up to what would probably be her full height, it still took the right clothing and dim lighting and her most imperious hightown accent for her to pass as a grown woman.

Even then she might not pass as a pearly. Not all pearlies had really been pearl divers, true, but most were old. Normally it took a lifetime of soaking in swampwater to acquire that much guile. But there were exceptions, and most of her customers came to her by referral, already assured of her competence. Certainly the man across the table was giving her due respect.

He’d given his name as Andry Gerard from Damnable Swamp, an outlying fishing village Yonie had heard of but never needed to visit. Gerard had a sunburned, stubbled face and muscular shoulders under his faded shirt. He hadn’t yet unclenched his jaw since he’d come in, and he kept his fingers pinched tight around the drawstring of a canvas carry-bag.

“It come to me in a fish,” he said. His eyes flicked away from hers as he set the bag down on the table. “A Fish o’ Fate, ma’am — you know?”

“Indeed?” Yonie raised one eyebrow. Around Wicked Ford, finding odd objects inside a fish’s belly was normally no fairytale event. As in most parts of the Bad Bayous, cemeteries flooded often and stone crypts were only for the rich. Finds ranged from the prosaic (turtleshell buttons, clay bottle-stoppers) to the faintly interesting (old pennies, keys) to the downright disgusting (finger-bones, yellowed human teeth.) The local fish weren’t fussy. They were avid for anything that so much as gleamed or twitched in the current.

There were always stories, of course, about fish who swallowed richer fare — rings for the finger or the ear, gold coins, ivory combs and jeweled silver belt-buckles. These Fish of Fate then sacrificed their treasure on the gutting-knife of a deserving fisherman or the dinner plate of a poor widow. Yonie enjoyed such tales, although LaRue always pointed out that firsthand accounts were rarer than dry feet in Devil’s Marsh.

“It must have been quite a large fish, sir,” she said in what she hoped was a cool, professional voice. “Did you catch it yourself?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

Yonie tried not to stare too obviously at the carry-bag on the table. It was heavy canvas, too stiff to reveal the shape of its contents, with a little blue-glass wily-charm at the end of the drawstring. Yonie’s father had had one like it, to keep his lunch dry when he took the fishing boat out on rainy days.

Yonie hated handling business by herself, but LaRue had gone out hunting and there was no knowing when she’d be back. It was too bad — Yonie felt much more confident with her there, even though LaRue couldn’t take part in the conversation. Also, LaRue had promised to bring her something, and Yonie hadn’t eaten since dinner last night.

“Have you had a Seeing done before, sir? No? Well, I charge ten coppers to examine an object. I can tell you if it’s guileful, and in most cases I can determine the nature of its wiles. I also take payment in kind,” she added, seeing Gerard’s stricken look. “A chicken, for instance, or a string of trout.”

“Got a couple o’ sand-crabs we been feeding up on the kitchen scraps. My wife’ll cook ’em up for you if she’s feeling better. She’s been ‘ere nine years now, but she still knows ‘er Northern spices.”

Yonie’s stomach scraped loudly. She moved her chair to cover the noise, feeling that it might decrease the dignity of her regal nod. Gerard didn’t know it, but she would have been happy with a pigeon wing.

Gerard pulled the bag open and lifted out a bulky item shrouded in a cloth. He flipped back the covering with a quick, convulsive motion, to reveal the ugliest ornament Yonie had ever seen. Two black-and-white steer horns had been varnished and inset in a platform of polished bone. They curved up and together to form a steep arch not found on any cattle skull in nature. Suspended from their points by corroded chains was a disc of tarnished brassy metal, indented in a spiral pattern like the cinnamon buns they sold at the Blackmire Inn.

“I’ll need some time alone to look at this, m’sir Gerard. Could I ask you to return at, say, the eighth hour tonight?” LaRue should be back by then. She would have to be.