Fiction Excerpt: “The Whited Child”

By Michael Canfield

Illustrated by Bernie Mireault

from Black Gate 9, copyright © 2005 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

Bad Pete’s livestock pen fence were down, and not a pig remained. Coyotes done that, but the White Mountains sent them. The mountains were the boss. Coyotes raided the coop too, leaving just one old hen that hardly never laid.

Bad Pete’s livestock pen fence were down, and not a pig remained. Coyotes done that, but the White Mountains sent them. The mountains were the boss. Coyotes raided the coop too, leaving just one old hen that hardly never laid.

Bad Pete took out his slicing knife and eyeballed that little hen. He curled his beard in a finger. “You best drop an egg or into my stew pot you go, girl.” The hen gulped and squeezed, but it weren’t no good. She didn’t have no egg in her.

She made a mean stew, stringy and lean, but Pete ate every bit of her and sucked the marrow.

He sat up all night in the chill looking at the fire, gnawing a twig, and talking to the White Mountains. The White Mountains didn’t say nothing back. Bad Pete alone of a men was allowed to live in the White Mountains, but he felt they had lately disfavored him.

He sat a day and a night, hunger gnawing strong. Come dawn the third day, a shadow moved on the horizon. It were the idiot boy, meaning white death had touched another town child at last, and Bad Pete was saved.

The one the town folk called the idiot boy come up, looking skinny and dusty as tumbleweed. There weren’t a townsman yet who would come into those White Mountains himself, even to save his kin. The idiot boy did it for a handful of corn — maybe an egg or two if he struck a good bargain.

The idiot boy took his pet mouse from his pocket and started petting it. When he had to talk to someone he always did that first.

“There’s a one who caught herself the White,” said the idiot boy.

“How old?” said Bad Pete.

“Near to my age, I expect.”

“His kin got pigs?”

The boy frowned. “Ain’t no pigs left this year.”

Bad Pete spat at the smoldering campfire. Town folk were all liars. “They got anything then?”

The boy looked confused. “Sure! They only the richest and fanciest bunch in town.” He caught himself too late.

“Rich folk. How many goats? And chickens?”

“Not so many.”

“That right? And who’s gonna stand for the whited child?”

“Got’s himself a grandma who will.”

That’ll do. “You tell that rich man it’s three goats and twenty chickens.”

The boy put the mouse away carefully. He placed his hands together. “Ain’t but that many chickens in the whole countryside! No fellow can pay that much for one cure, lest the whole bunch of ‘em starve to save a sickling!”

“You tell him that’s the price, if he don’t like it maybe he can perform the cure his self.”

“I think this fellow just soon let his kin die as hand over all them goats and chickens as you want.”

“Stingy is he?”

“It’s stingy times, ain’t it?”

“Two goats, fifteen chickens.”

The boy slapped his head, and fell back. “And the sun and the moon besides, I guess. One goat and three chickens. That’s a fair price.”

“A fair price for fixing a child’s got the White on it?”

“He got other’n.”

“Two goats and ten chickens — and good egg-layers too, and get your runty ass away now before I chop you up for dinner.”

The idiot boy grinned. He was missing another tooth since last month. “Ain’t you nor no coyote, nor nothing in these hills fast enough to catch me!” He scattered off down the slope.

Bad Pete hollered. “You tell that rich ‘n have the Whited child and the payment here by sundown, or ain’t no deal!”

He stood and his old knees cracked. He chuckled. The idiot boy was worth twenty of them townsmen by Bad Pete’s reckoning.

Just the thought of a mess of eggs and a swallow of goat’s milk whet his appetite. He needed to hit out into the hills and get set for the swap. He had to chop him down a bristlecone, for one thing, and burn it to cinders, and gather milkweed. The swaps don’t come cheap.

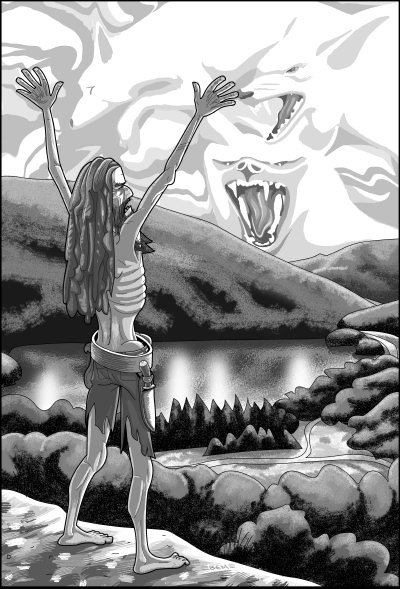

The idiot boy got back by sundown. He led his charges like a little caravan: goats with caged chickens strapped on, old granny, and whited child. Bad Pete got ready. He stood naked, but for belt and slicing knife. He started rubbing the milkweed and ashes over his skin. He rubbed fast. Them White Mountains was rumbling. They was angry now with four human folk on the slopes.

The whited child was just strong enough to walk and she hobbled behind her granny, grabbing onto a bunch of fabric for support. She was whited bad. Her skin was about the same shade as those blanched mountains at noon day. Her gums were the same. Her small eyes nearly dried up in the sockets. Her hair was gone, but for a few rust-colored strands, her fingernails had already cracked off, and she was a’ bent and hobbled as her granny.

Exhausted from their climb, the granny and the whited child were too weak to be frightened by Bad Pete, naked and ash-covered, bathed in the setting sun. He’d lost more than one job because folks run screaming into the night when they saw him. Coyotes took them on their own, and Bad Pete got nothing.

Now the sun’s last rays faded, and the coyotes gathered in the brush outside the camp, their eyes reflecting moonlight. Everything was hungry on the slopes. Bad Pete told the idiot boy take the goats and chickens and pen them up good, then get on home. He didn’t like spectators. The boy obeyed, then disappeared down the hill. The whited child looked after him, but she bravely kept her place. Her granny clutched hands with her.

Bad Pete growled at the granny. “Only I can do the swap. Only I can save your kin. You understand what you are asking of me? If not, turn your ass around and get off these hills.”

The granny nodded slowly. “Yes, sir,” she said. “I know what I’m asking.” She shook, but she was willing.

“Come on then,” he said.