Feature Excerpt: “Back to the Future: Modern Reprints of Classic Fantasy”

By Rich Horton

From Black Gate 14

From Black Gate 14

Copyright © 2010 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

Much has been made in recent years of “the death of the midlist” – the tendency of publishers to focus on big sellers at the expense of modest earners.

The same tendency can hurt the backlist as well, making it harder to find reprints of older books. This is complicated by a number of factors – a simple one is that the explosion in new titles has made it harder to find bookstore space for reprints.

In the 1960s and before, I am told, devoted SF readers could read the entire field in a given year – all the magazines, and all the new novels.

By the mid-70s, when I started reading in the field, that was hardly possible, but I did expect to read all the prominent novels, and at the same time catch up on what I had missed (while not being alive).

And there were old books to find – Signet, for instance, reprinted pretty much the complete works of Robert Heinlein. The Ballantine Adult Fantasy series brought classics by the likes of Hope Mirrlees, James Branch Cabell, and Evangeline Walton back to print.

And fairly recent paperback reprints of most every book – it seemed to me – from the past decade or so were available.

Nowadays it’s much harder to find recent reprints, and I think it’s at least a bit harder to find classic reprints.

Nowadays it’s much harder to find recent reprints, and I think it’s at least a bit harder to find classic reprints.

It used to be normal for every hardcover book to get a mass market paperback edition, typically about a year later. And of course there were many paperback originals.

These paperbacks, if at all commercially successful, seemed to remain in print for years, and to go through several reprintings, and occasional new editions.

In recent years, many hardcovers never get a mass market edition – some appear as “trade” paperbacks, some are never reprinted at all. And the shelf life of mass market paperbacks, at least, is shrinking.

So where does a new reader go to find books by a writer he might have encountered in an anthology, or read about in some review column?

The library is still an option – Nichols Library in Naperville, IL, certainly fed much of my early SF jones. But libraries are pressed for space, and plenty of older books are deaccessioned. And somehow it doesn’t seem to me that “them dern kids” use the library as much anymore. (But perhaps that’s just me!)

The good news is that some publishers are still making an active effort to reprint older books, classics of our field.

Baen

Some years ago I noticed a commotion on the Usenet newsgroup rec.arts.sf.written. Eric Flint, a Baen writer who had attracted positive notice with his first couple of novels (particularly 1632), was going to edit for Baen a series of collections of the stories of James H. Schmitz.

Some years ago I noticed a commotion on the Usenet newsgroup rec.arts.sf.written. Eric Flint, a Baen writer who had attracted positive notice with his first couple of novels (particularly 1632), was going to edit for Baen a series of collections of the stories of James H. Schmitz.

This was widely regarded as wonderful news… with one exception. Flint proposed to edit the stories for the modern reader, a mixture of sensible changes like removing redundant material in stories published back to back, and less obvious changes like eliminating mentions of characters smoking, and updating slang to avoid dated phrases like “newshen.”

Even more radically, in at least one case Flint changed the names of characters to make an unconnected story fit into another series, and in another case, he sharply cut a story on the grounds (valid, in my opinion) that he was improving it.

The result was a bit of a dustup – and, in one curious case, an opportunity for one of Flint’s opponents in the thread to have his first novel published by Bean. (This writer, Ryk Spoor, has since become a Baen regular and a collaborator with Flint.)

What was almost – but not quite – missed was the central fact that the end result of Eric Flint’s efforts was eventually to restore every word James Schmitz published (well, every word but “newshen” and a few others!) to print.

What was almost – but not quite – missed was the central fact that the end result of Eric Flint’s efforts was eventually to restore every word James Schmitz published (well, every word but “newshen” and a few others!) to print.

Baen began with a collection featuring Schmitz’s most popular character, Telzey Amberdon, and continued with a number of books including well-known stories such as the Agent of Vega pieces, and finally concluded with a generous trade paperback containing the rest of Schmitz’s work, Eternal Frontier.

This was in the end extremely rewarding. Schmitz’s work is very fun, and it was a delight to see it all available. I like it enough that I had tracked down most (but by no means all!) of his stuff in used bookstores. But there were stories I had no idea existed, from mystery magazines for example.

And Baen (that is to say Flint) wasn’t done.

Before long a number of collections of such well known but not well reprinted writers as Randall Garrett and Murray Leinster were back in print.

And Flint also resurrected some more obscure folks. Tom Godwin, remembered these days almost entirely for a single story, “The Cold Equations,” was represented by a collection that included that story and several others, such as his well-regarded novel The Survivors.

And Flint also resurrected some more obscure folks. Tom Godwin, remembered these days almost entirely for a single story, “The Cold Equations,” was represented by a collection that included that story and several others, such as his well-regarded novel The Survivors.

An even more obscure writer is Howard Myers, who also wrote as Verge Foray, mostly in the late ‘60s for Analog, before dying fairly young. A number of Myers/Foray stories appeared in a large trade paperback called The Creatures of Man.

Honesty compels me to admit that I was underwhelmed by this particular book – most of Myers’ work strikes me as at best unmemorable, at worst queasily sexist. One curious value is that the Foray stories from Analog represent something of a documentation of the decline of the magazine in John W. Campbell’s last years.

Other writers resurrected include Keith Laumer, Henry Kuttner, and Christopher Anvil. These writers seem an interesting sampling of mostly the middle range of writers who worked largely (though by no means entirely) for John W. Campbell at Astounding/Analog in the ‘50s and ‘60s.

They did their best work at shorter lengths, and they were reliably entertaining and often thought-provoking, but neither revolutionary nor particularly original. They are just the sort of writers who can be forgotten, in particular as they are hardly known at all for their novels. And that makes the Baen project of particular value.

(I should mention a couple of other writers Baen has reprinted that seem less obviously “resurrections:” Poul Anderson and Cordwainer Smith.)

SF/Fantasy Masterworks

The British publishing company Orion, via their imprints Millennium and later Gollancz, took a different tack in keeping important SF in print.

The British publishing company Orion, via their imprints Millennium and later Gollancz, took a different tack in keeping important SF in print.

The SF Masterworks series, beginning in 1999, undertook to reprint the very best science fiction novels of the past century or so.

Of course this was restricted to some extent by availability of reprint rights, but on the whole the list is quite remarkable.

As of now it runs to some 70 books, including Joe Haldeman’s The Forever War, James Blish’s Cities in Flight, Gene Wolfe’s The Fifth Head of Cerberus, Olaf Stapledon’s Last and First Men, Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Dispossessed, H. G. Wells’s The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds, Samuel R. Delany’s Nova, Frank Herbert’s Dune, Robert Heinlein’s The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, and too many more to mention (Wikipedia has a complete list.)

I said they reprinted novels, and that’s mostly true, but there were a couple of story collections slipped in, including most significantly (to my mind) The Rediscovery of Man, by Cordwainer Smith, the complete stories of one of the oddest and most intriguing SF writers ever.

Other interesting works included that seem significant to me because they are first rate but not necessarily as well known as some of the books listed above include what may be Jack Vance’s best singleton novel, Emphyrio; M. John Harrison’s cynical take on Space Opera, The Centauri Device; Michael Moorock’s colorful and louche science fantasy, The Dancers at the End of Time (always my personal favorite among his works); one of the most significant works from Russia: Roadside Picnic, by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky; and the complete “Roderick” novels by John Sladek, brilliant satire from one of the field’s best and darkest satirists.

Other interesting works included that seem significant to me because they are first rate but not necessarily as well known as some of the books listed above include what may be Jack Vance’s best singleton novel, Emphyrio; M. John Harrison’s cynical take on Space Opera, The Centauri Device; Michael Moorock’s colorful and louche science fantasy, The Dancers at the End of Time (always my personal favorite among his works); one of the most significant works from Russia: Roadside Picnic, by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky; and the complete “Roderick” novels by John Sladek, brilliant satire from one of the field’s best and darkest satirists.

There is a parallel series of Fantasy Masterworks. This is quite as valuable.

I was particularly impressed by the second volume: Time and the Gods, a compilation of Lord Dunsany’s absolutely seminal early set of six collections of generally very short but remarkably imaginative fantasy tales.

This book was particularly important to me – it filled in a shortfall in my reading, showing me how important Dunsany was to forming the Fantasy genre.

Oddly, given that contemporary fantasy seems dominated by long novels and trilogies, the Fantasy Masterworks series has quite a few story collections: an anthology of Rudyard Kipling’s best fantasy stories, a Leigh Brackett collection, a compilation of Jack Vance’s Dying Earth stories, C. L. Moore’s Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams, and two volumes of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser tales from Fritz Leiber.

Oddly, given that contemporary fantasy seems dominated by long novels and trilogies, the Fantasy Masterworks series has quite a few story collections: an anthology of Rudyard Kipling’s best fantasy stories, a Leigh Brackett collection, a compilation of Jack Vance’s Dying Earth stories, C. L. Moore’s Black Gods and Scarlet Dreams, and two volumes of Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser tales from Fritz Leiber.

Other significant books in the series include (in two volumes) Gene Wolfe’s complete Book of the New Sun; Hope Mirrlees’s Lud-in-the-Mist; John Crowley’s Little, Big; George R. R. Martin’s Fevre Dream; Geoff Ryman’s Was; and Evangeline Walton’s The Mabinogion. The entire list can be found on Wikipedia.

A related series also appeared around the turn of the millennium from Gollancz. At the time the SF Masterworks series was coming out under the Millennium imprint. Orion, as noted, also controls the Gollancz imprint. Gollancz was the primary source of British SF in hardcover back in the ‘60s – a little bit like Doubleday in the US at the same time.

Gollancz’s SF line appeared with plain yellow dust jackets – no cover art. So they put out a series called Gollancz SF Collectors’ Editions – in large-sized paperback, not hardcover, but will cute yellow covers, and even flaps.

By and large this series features less prominent works than the SF Masterworks line, but in an odd way that makes it more interesting.

A lot of the selections ended up being worthwhile books in some danger of being forgotten. Examples include Daniel F. Galouye’s Hugo nominee Dark Universe, William Tenn’s Of Men and Monsters (his only full-length novel), and John Sladek’s viciously funny Tik-Tok, about a robot that goes decidedly off the track of Asimov’s Three Laws.

A lot of the selections ended up being worthwhile books in some danger of being forgotten. Examples include Daniel F. Galouye’s Hugo nominee Dark Universe, William Tenn’s Of Men and Monsters (his only full-length novel), and John Sladek’s viciously funny Tik-Tok, about a robot that goes decidedly off the track of Asimov’s Three Laws.

They also reprinted the wonderful Floating Worlds, by Cecelia Holland, best known for her historical novels; and Ursula K. Le Guin’s first short story collection, The Wind’s Twelve Quarters, in my view arguably the best single-author collection ever (not counting “Complete Stories” type books).

Also Ian Watson’s strange and fascinating early linguistics-themed novel, The Embedding, and early work by John Crowley and Octavia Butler.

Alas, I have not been able to find a complete list of the Gollancz SF Collector’s Editions.

One more much less prominent UK series, again from the turn of the millennium, was the Voyager Classics, a set of 36 books in, again, attractive paperback editions (with flaps).

It was rather idiosyncratic, with some obvious classics in no danger of going out of print, like The Lord of the Rings, Foundation, and The Martian Chronicles; as well as some significant recent works like Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy; and a couple of mild surprises, like some David Eddings, and the fairly obscure Philip Dick novel The Game-Players of Titan.

For the most part though it’s a somewhat narrow but rather worthy set of mostly quite well known books.

SFBC

Beginning in 2003, their 50th anniversary, the Science Fiction Book Club for five years issued a series of eight books per year representing the best books of each decade from the ‘50s through the ‘90s.

Beginning in 2003, their 50th anniversary, the Science Fiction Book Club for five years issued a series of eight books per year representing the best books of each decade from the ‘50s through the ‘90s.

The end result is 40 books that do a fine job of summarizing the peaks of SF over the last half of the 20th Century.

Again, by concentrating (understandably) on the best, there is a certain sense that the books preserved in this set are those that are more likely to be available anyway.

But not always!

Among the classics the SFBC reprinted are Clifford Simak’s City; Frank Herbert’s first novel, Under Pressure; Startide Rising, by David Brin; Orson Scott Card’s Ender’s Game; The Anubis Gates, by Tim Powers (one of my very favorite novels); Alexei Panshin’s Rite of Passage; Ursula K. Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness; Rats and Gargoyles, by Mary Gentle; and Snow Crash, by Neal Stephenson.

And one can see that while many are still widely available (the Le Guin, the Card, the Stephenson, surely), many others are more obscure to newer readers: City, for example, is just the sort of quiet and unspectacular older book whose once high reputation in the field is in danger of eclipse.

Wildside

One approach to bringing books with (perhaps) less sales potential back to availability is Print on Demand.

One approach to bringing books with (perhaps) less sales potential back to availability is Print on Demand.

Wildside Press, in particular, has built up a tremendous list of interesting titles. Their books are attractive trade paperbacks (and sometimes also hardcovers). They publish a huge variety, in many genres.

Among the most intriguing SF writers they feature are Avram Davidson and Barrington J. Bayley. Their Davidson selection includes most of his early novels, idiosyncratic if not wholly successful stories like Rork!, The Enemy of My Enemy, and the diptych Rogue Dragon/The Kar-Chee Reign.

His somewhat later and more characteristically Davidsonian novels Peregrine: Primus and Peregrine: Secundus are also available: delightful stories set in a Late Roman Empire that never was.

From Bayley one can find, for example, Collision With Chronos, The Fall of Chronopolis, and The Soul of the Robot, three fine examples of work during his most productive period; and also two late novels that were Wildside originals: The Sinners of Erspia and The Great Hydration.

Among the many other writers you can find at Wildside are Lester Del Rey, Lawrence Watt-Evans, Sheila Finch, and Brian Stableford.

NESFA Press

Small presses, as ever, pick up much of the slack, and one of the best at reprinting classic SF short fiction in NESFA Press, the publishing arm – er, pseudopod – of the New England Science Fiction Association.

Small presses, as ever, pick up much of the slack, and one of the best at reprinting classic SF short fiction in NESFA Press, the publishing arm – er, pseudopod – of the New England Science Fiction Association.

For many years they routinely did a slim book (a strictly limited edition) by the guest of honor at the NESFA convention, Boskone.

But in 1991 they began a series called “NESFA’s Choice” – collections of stories by significant SF writers whose work was becoming unavailable.

Ironically, just as with Baen, they began by publishing The Best of James H. Schmitz. They continued with a very important book (to my mind): The Rediscovery of Man: The Complete Short Fiction of Cordwainer Smith.

As of now the NESFA’s Choice series runs to 43 titles, many of them very thick.

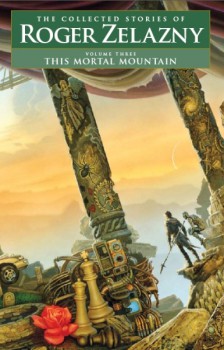

On occasion they have done complete short fiction collections (sometimes in multiple volumes) – so far, besides Smith, there are complete collections of Charles Harness, William Tenn, and an ongoing project to reprint the complete short stories of Roger Zelazny.

On occasion they have done complete short fiction collections (sometimes in multiple volumes) – so far, besides Smith, there are complete collections of Charles Harness, William Tenn, and an ongoing project to reprint the complete short stories of Roger Zelazny.

Other authors they have reprinted include Zenna Henderson, Chad Oliver, Judith Merril, John W. Campbell, A. E. Van Vogt, Jane Yolen, Hal Clement, Eric Frank Russell and many more.

A new project (though not a complete stories!) is tackling Poul Anderson. And they have even done original novels – in particular two by a favorite of mine, Charles Harness.

3 thoughts on “Feature Excerpt: “Back to the Future: Modern Reprints of Classic Fantasy””