Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: The Sign of the Z!

The Mark of Zorro (1940)

November 27, 1920, a century ago plus a few weeks, saw the release of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr.’s The Mark of Zorro, and the beginning of the swashbuckler film as we know it. There was a lot more Zorro to follow, some of it very good indeed, so this week we’re looking at the early post-silent career of the Masked Man in Black.

The Mark of Zorro

Rating: ***** (Essential)

Origin: USA, 1940

Director: Rouben Mamoulian

Source: Fox Studio Classics DVD

Tyrone Power’s family had been on the stage for generations, and he considered himself a serious actor. He finally broke into the movies in the mid-1930s and became a popular leading man for 20th Century Fox in parts both serious and not-so-serious. Meanwhile Warner Bros. was making a pile from Errol Flynn’s swashbucklers; though Fox didn’t have Flynn, they did have Power, and Darryl F. Zanuck decided Power was going to be Fox’s sword-slinging hero. To launch him in that new role they chose to remake The Mark of Zorro, the film that had launched Douglas Fairbanks, Sr.’s swashbuckling career. It wasn’t the kind of part Power really wanted to play, but he dutifully agreed, and the result was a classic that typecast him, rightly or wrongly, for the rest of his career.

This new Mark of Zorro was no slavish remake: the screenwriters rewrote the story from top to bottom, retaining its familiar and iconic elements but adding new ones, such as naming the ruler of colonial Los Angeles the “Alcalde,” a title that became standard thereafter. But first they tacked on a prologue, showing Don Diego as a cadet in the hussars in Madrid, romancing the ladies and dueling the other young hot-bloods. Then his father summons him back to California, where he expects there’ll be no one at all to fight — so he abandons his sword by thrusting it into the ceiling (a nice callback to Fairbanks, who did the same thing at the end of his Mark of Zorro).

However, California is not the peaceful backwater Diego remembers. His father, the Alcalde, is Alcalde no more, forced out and replaced by the brutal Don Luis Quintero, who runs Los Angeles as a private fief for the enrichment of himself and his enforcer, Capitan Esteban. But it’s not all bad, for the new Alcalde has a sweet, clever, and beautiful niece named Lolita.

Meanwhile, the peons are taxed into destitution, those who can’t pay are whipped, and even the sanctuary of the church is violated — so Zorro must ride! And it turns out Power is tailor-made for the part: he’s dashing, romantic, and swordsman enough for the role of Zorro, and he has the sly comic touch needed to play the effete fop Don Diego.

In this sort of film, the hero is key, of course, but all the best swashbucklers feature a top-notch supporting cast, and this is no exception. To help launch their rival to Errol Flynn, Zanuck cannily hired two of the standouts from The Adventures of Robin Hood, namely Basil Rathbone for the role of the arrogant Capitan Esteban, and Eugene Pallette to play Fray Felipe, who is essentially Friar Tuck transported from Old England to New Spain. Linda Darnell also does fine as the dewy love interest Lolita, but the prize goes to Gale Sondergaard arching her astounding eyebrows as Inez Quintero, the Alcalde’s lascivious wife, who’s set her sights on Don Diego. She’s just delicious.

The two best scenes in this film are polar opposites: the first is where Power and Darnell bandy words as Zorro, disguised as a monk, flatters the gradually-catching-on Lolita; and the second is nearly the last, when Power and Rathbone cross swords for the final duel. It’s exciting, and even better, it’s convincing: “Tyrone,” said Basil Rathbone, “could have fenced Errol Flynn into a cocked hat.”

The Bold Caballero

Rating: *

Origin: USA, 1936

Director: Wells Root

Source: Alpha Video DVD

This is the first Zorro film of the sound era, made by Republic Pictures, a minor studio best known for cranking out twelve-part serials. In an astounding splurge this film was shot in full color, a rare thing in the mid-thirties. The story was “from an idea by Johnston McCulley,” Zorro’s creator, and was written and directed by Wells Root, who the following year would script the Ronald Colman version of The Prisoner of Zenda.

As we’re told before the movie begins, Zorro had been leading a Native American revolt against Spanish oppression but was captured, and thus starts the movie in captivity, on his way to the scaffold for execution. (It’s like an Elder Scrolls videogame!) Spoiler: he escapes!

Alas, the film is a typical low-budget Republic production, color notwithstanding: it looks cheap, the direction is shoddy, and the acting is uniformly terrible. Much of it is played for laughs, but the jokes are weak. Zorro/Don Diego de Vega is played by a handsome nonentity with no discernible talent named Robert Livingston. No, I never heard of him either. There’s an impostor Zorro, a weak murder mystery, a bullfight, a pallid romance, a lot of dusty galloping, and some truly feeble stunts in imitation of Doug Fairbanks.

To be fair, B-list actress Heather Angel does a passable job as the love interest, and there are a couple of laughs from an Austrian commandante character played by German comic actor Sig Rumann, better known for chasing the Marx Brothers around opera houses and racetracks. Everything else is just embarrassing.

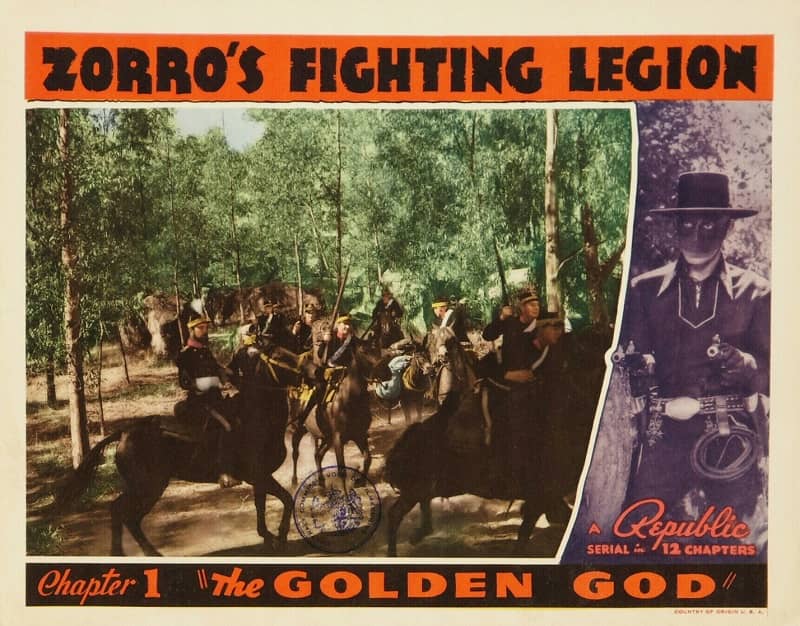

Zorro’s Fighting Legion

Rating: **

Origin: USA, 1939

Directors: William Witney and John English

Source: Hal Roach Studios DVD

Before there were weekly TV shows, there were movie serials released as weekly episodes, typically in twelve installments, shown as part of the “short subjects” that preceded a feature film. Zorro film adaptations are usually set in a distinctive historical time and place, more colonial New Spain than Old West. Not so the Republic Zorro serials of the Thirties and Forties, most of which are basically standard Westerns that happen to feature an outlaw swashbuckler, with Zorro relying on a six-gun rather than a sword. The exception is Zorro’s Fighting Legion, which is set in Mexico in 1824 and features the Zorro we know and love, the fop Diego Vega who dons black mask and sword to fight oppression and injustice. Unfortunately, it has all the flaws for which the Republic serials are notorious: the plot is thin, obvious, and repetitive, the characters are cardboard, production values are bottom of the barrel, and whoa, the acting….

Zorro is played by Reed Hadley, an actor at the high school drama level—which puts him above the rest of the cast, whose only skills seem to be riding, fighting, running, fencing, and falling over when powder kegs explode. That’s mostly okay, since frenetic action takes up 90% of this serial’s screen time, and the actors just speak to each other briefly in order to set up the next deadly peril. The only exception is the villain who plays Don-Del-Oro, the Big Bad who thunders his orders in a stentorian announcer’s voice from inside a golden god’s awesome but towering and ungainly metal mask. The rest of the cast are just glorified stunt men. But hey: good stunts!

The story is scarcely worth summarizing. The new Mexican republic needs gold from a certain mine to establish its government, but disloyal politicians in the service of a criminal mastermind want the gold for themselves. The top crook masquerades as Don-Del-Oro, an ancient god of the Yaqui tribe of Native Americans, come back to lead them against the white men. Zorro arrives to save the day, and since the local government is corrupt, he forms a “fighting legion” of citizens loyal to the republic to oppose them. The best thing about this fighting legion? They have a theme song! Whenever Zorro summons them, they leap on their horses and gallop to join him, singing, “We ride … men of Zorro are we!” I think it’s the first-ever Zorro song.

The portrayal of the Native Americans here is sad and unfortunate. In other films Zorro is a friend and defender of the oppressed natives, who are depicted with dignity and sympathy. Not here: the Yaqui are superstitious savages easily fooled and led astray by the villains. Only the good white men can straighten them out.

Despite this, there’s some stupid fun to be found in this three-and-a-half hour gallop-fest, especially if you’re under the age of thirteen or under the influence of powerful cold medications. Gunpowder must have been easy to come by in old Mexico, because damn near everything gets blown up; if a wagon strays near a cliff you can be sure it’s going over it; there’s a subterranean flood, beehive grenades, a peg-legged jailer, and a sort of Zorro-signal of brush arranged on hillsides in giant Zs that are set afire to summon the hero or his legion. Plus, the music by William Lava, who composed a frantic Mexican-tinged gallop, is surprisingly good.

The Sign of Zorro

Rating: ****

Origin: USA, 1958

Director: Lewis R. Foster / Norman Foster

Source: Disney+

Disney’s Zorro TV series had continued stories like an old-time serial, with what we’d now call story arcs of thirteen episodes each. This feature is a compilation of the first, or “Monastario” story arc from the start of the first season. Though it’s episodic and it’s easy to see the seams where the chapters were stitched together, compressing thirteen 25-minute episodes into one 90-minute story definitely sharpens and improves the storytelling.

Not that it needed much improving. The Zorro series was the pinnacle of the Disney studio’s live action productions, well-acted, sharply written, and tightly directed; if you’ve never seen it, this is a fine introduction, with all its virtues presented in capsule form.

The basic story doesn’t stray from the one told in The Mark of Zorro in its 1920 and 1940 incarnations: in 1820, Diego de la Vega (Guy Williams), the son of one of the leading landholders of southern California, returns from his studies in Spain to find that the pueblo of Los Angeles is under the tyrannical rule of a corrupt commandante. The crimes of Capitán Monastario (Britt Lomond) are so outrageous that the rancheros, led by Don Alejandro de la Vega (George Lewis), are ready to rise in open revolt. Diego realizes this will lead to their defeat and his father’s death, so he adopts the guise of the outlaw Zorro to oppose Monastario in their place.

Williams is a fine Zorro in the athletic swashbuckler tradition of Doug Fairbanks, Sr. and Tyrone Power, climbing adobe walls, leaping from tile roofs, and rearing against the horizon on Tornado, his famous black stallion. The swordplay, with period-appropriate small swords and cavalry sabers, is quite good, which is no surprise as the fencing master was Fred Cavens, who also coached Fairbanks and Power. The wicked Monastario is a worthy opponent, clever and courageous, and after a series of clashes he deduces who Zorro must be behind his black mask and nearly exposes him to the visiting Viceroy of Mexico, and then … but no, see it for yourself.

The previous installments in the Cinema of Swords are:

Olivia de Havilland — First Queen of the Swashbucklers

Goofballs in Harem Pants

Disney’s Early Swashbucklers

‘50s Vikings – Havoc in Horned Helms

Laughing Cavaliers

Charming and Dangerous: Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.

Eleven Samurai: Early Chambara Classics

Beyond Captain Blood: Three by Sabatini

3 Musketeers + 1 Long Nose

Louis Hayward, Everyman with a Sword (Part 1 of 2)

Days of Technicolor Knights

Louis Hayward, Everyman with a Sword (Part 2 of 2)

Laurence Olivier, Swashbuckler?

Tony Curtis Goes Yonda

The 7th Voyage and Its Children

The Good, the Bad, and Mifune

The First British Invasion

Wholesome Buccaneers (Pt. 1)

The Tale of Zatoichi

LAWRENCE ELLSWORTH is deep in his current mega-project, editing and translating new, contemporary English editions of all the works in Alexandre Dumas’s Musketeers Cycle, with the fourth volume, Blood Royal, just published by Pegasus Books in the US and UK. His website is Swashbucklingadventure.net.

Ellsworth’s secret identity is game designer LAWRENCE SCHICK, who’s been designing role-playing games since the 1970s. He now lives in Dublin, Ireland where he works as a consultant for narrative-based video games.

The Mark of Zorro is, along with The Adventures of Robin Hood and Gunga Din, one of the three great classic adventure movies of Hollywood’s golden age. They put most current action/buddy/adventure movies to shame.

And the fight between Power and Rathbone is, in my opinion, the screen’s greatest swordfight, by a large margin.

“It is the number two…”

I haven’t watched The Mark of Zorro in many years and I need to re-watch it.

My father, once a champion fencer, used to say the duel between Power and Rathbone was the finest fencing on film. One of the reasons for this lofty praise was that my dad claimed you can actually see Rathbone miss his parry, allowing Power to run him through.

As a youthful ne’er-do-well I always thought that was kinda hardcore, inside baseball fencing stuff, but cool.

I admit that I never actually saw that detail when I watched the film and, back in those sepia-toned pre-VCR days, I couldn’t rewind the movie to check it out.

So I really need to watch it again.

Another Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords!

I’ve seen parts of Fairbanks’s Zorro, and I think that fight between Power and Rathbone is superb, but it was Disney’s Zorro that captured my imagination as a boy.

I think I need to watch them all again.

Thank you, Mr. Ellsworth!

> My father, once a champion fencer, used to say the duel between Power and Rathbone was the finest fencing on film.

John,

I can’t recall watching this version of Zorro in my youth, and I now see that’s a serious oversight!

*Dashes off to check streaming services for MARK OF ZORRO…*